Wetting

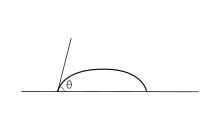

Wetting is the ability of a liquid to displace gas to maintain contact with a solid surface, resulting from intermolecular interactions when the two are brought together.

Wetting has gained increasing attention in nanotechnology and nanoscience research, following the development of nanomaterials over the past two decades (i.e., graphene,[5] carbon nanotube, boron nitride nanomesh[6]).

Since these solids are held together by weak forces, a very low amount of energy is required to break them, thus they are termed "low-energy".

An ideal surface is flat, rigid, perfectly smooth, chemically homogeneous, and has zero contact angle hysteresis.

[9][13] The following derivations apply only to ideal solid surfaces; they are only valid for the state in which the interfaces are not moving and the phase boundary line exists in equilibrium.

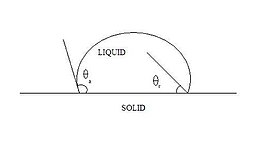

The components of net force in the direction along each of the interfaces are given by: where α, β, and θ are the angles shown and γij is the surface energy between the two indicated phases.

If three fluids with surface energies that do not follow these inequalities are brought into contact, no equilibrium configuration consistent with Figure 3 will exist.

With improvements in measuring techniques such as AFM, confocal microscopy and SEM, researchers were able to produce and image droplets at ever smaller scales.

, a geometric property of a sessile droplet to the bulk thermodynamics, the energy at the three phase contact boundary, and the curvature of the surface α.

This simplification nevertheless yields results that are relevant for the adsorption of water under realistic conditions and the use of ice for the theoretical simulation of wetting is commonplace.

This is a kinetic nonequilibrium effect which results from the contact line moving at such a high speed that complete wetting cannot occur.

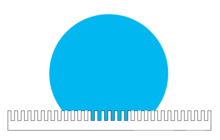

[34] The Wenzel model [35] describes the homogeneous wetting regime, as seen in Figure 7, and is defined by the following equation for the contact angle on a rough surface:[36] where

A case that is worth mentioning is when the liquid drop is placed on the substrate and creates small air pockets underneath it.

Experimental results regarding the surface properties of Wenzel versus Cassie–Baxter systems showed the effect of pinning for a Young angle of 180 to 90°, a region classified under the Cassie–Baxter model.

[38][39] With the advent of high resolution imaging, researchers have started to obtain experimental data which have led them to question the assumptions of the Cassie–Baxter equation when calculating the apparent contact angle.

A theory that preserves the Cassie–Baxter equation while at the same time explaining the presence of the minimized energy state of the triple line hinges on the idea of a precursor film.

Furthermore, this precursor film allows the triple line to bend and take different conformations that were originally considered unfavorable.

This precursor fluid has been observed using environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) in surfaces with pores formed in the bulk.

With the introduction of the precursor film concept, the triple line can follow energetically feasible conformations, thereby correctly explaining the Cassie–Baxter model.

The red rose takes advantage of this by using a hierarchy of micro- and nanostructures on each petal to provide sufficient roughness for superhydrophobicity.

The lotus leaf has a randomly rough surface and low contact angle hysteresis, which means the water droplet is not able to wet the microstructure spaces between the spikes.

The rose petal's micro- and nanostructures are larger in scale than those of the lotus leaf, which allows the liquid film to impregnate the texture.

Since the solid can be considered an absorptive material due to its surface roughness, this phenomenon of spreading and imbibition is called hemiwicking.

If the contact angle is less than ΘC, the penetration front spreads beyond the drop and a liquid film forms over the surface.

In this state, the equilibrium condition and Young's relation yields: By fine-tuning the surface roughness, it is possible to achieve a transition between both superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic regions.

While taking into account capillary, gravitational, and viscous contributions, the drop radius as a function of time can be expressed as[45] For the complete wetting situation, the drop radius at any time during the spreading process is given by where Many technological processes require control of liquid spreading over solid surfaces.

When surfactants are absorbed onto a hydrophobic surface, the polar head groups face into the solution with the tail pointing outward.

Thus, the contact angle changes based on the following equation:[46] As the surfactants are absorbed, the solid–vapor surface tension increases and the edges of the drop become hydrophilic.

Both PVFc and PFcMA have been tethered onto silica wafers and the wettability measured when the polymer chains are uncharged and when the ferrocene moieties are oxidised to produce positively charged groups, as illustrated at right.

[47] The contact angle with water on the PFcMA-coated wafers was 70° smaller following oxidation, while in the case of PVFc the decrease was 30°, and the switching of wettability has been shown to be reversible.