Josiah Willard Gibbs

As a mathematician, he created modern vector calculus (independently of the British scientist Oliver Heaviside, who carried out similar work during the same period) and described the Gibbs phenomenon in the theory of Fourier analysis.

Working in relative isolation, he became the earliest theoretical scientist in the United States to earn an international reputation and was praised by Albert Einstein as "the greatest mind in American history".

[3] In 1901, Gibbs received what was then considered the highest honor awarded by the international scientific community, the Copley Medal of the Royal Society of London,[3] "for his contributions to mathematical physics".

He is chiefly remembered today as the abolitionist who found an interpreter for the African passengers of the ship Amistad, allowing them to testify during the trial that followed their rebellion against being sold as slaves.

[13][14] Though in later years he used glasses only for reading or other close work,[13] Gibbs's delicate health and imperfect eyesight probably explain why he did not volunteer to fight in the Civil War of 1861–65.

They spent the winter of 1866–67 in Paris, where Gibbs attended lectures at the Sorbonne and the Collège de France, given by such distinguished mathematical scientists as Joseph Liouville and Michel Chasles.

[23] Having undertaken a punishing regimen of study, Gibbs caught a serious cold and a doctor, fearing tuberculosis, advised him to rest on the Riviera, where he and his sisters spent several months and where he made a full recovery.

[32] Although the journal had few readers capable of understanding Gibbs's work, he shared reprints with correspondents in Europe and received an enthusiastic response from James Clerk Maxwell at Cambridge.

"[39] Gibbs's monograph rigorously and ingeniously applied his thermodynamic techniques to the interpretation of physico-chemical phenomena, explaining and relating what had previously been a mass of isolated facts and observations.

Nevertheless it was a number of years before its value was generally known, this delay was due largely to the fact that its mathematical form and rigorous deductive processes make it difficult reading for anyone, and especially so for students of experimental chemistry whom it most concerns.

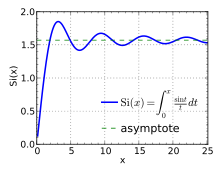

In other mathematical work, he re-discovered the "Gibbs phenomenon" in the theory of Fourier series[47] (which, unbeknownst to him and to later scholars, had been described fifty years before by an obscure English mathematician, Henry Wilbraham).

Except for his customary summer vacations in the Adirondacks (at Keene Valley, New York) and later at the White Mountains (in Intervale, New Hampshire),[59] his sojourn in Europe in 1866–1869 was almost the only time that Gibbs spent outside New Haven.

[63] Beyond the technical writings concerning his research, he published only two other pieces: a brief obituary for Rudolf Clausius, one of the founders of the mathematical theory of thermodynamics, and a longer biographical memoir of his mentor at Yale, H. A. Newton.

[69] In an electrochemical reaction characterized by an electromotive force ℰ and an amount of transferred charge Q, Gibbs's starting equation becomes The publication of the paper "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances" (1874–1878) is now regarded as a landmark in the development of chemistry.

[77][78] Gibbs was well aware that the application of the equipartition theorem to large systems of classical particles failed to explain the measurements of the specific heats of both solids and gases, and he argued that this was evidence of the danger of basing thermodynamics on "hypotheses about the constitution of matter".

[80] British scientists, including Maxwell, had relied on Hamilton's quaternions in order to express the dynamics of physical quantities, like the electric and magnetic fields, having both a magnitude and a direction in three-dimensional space.

[6][87] In that work, Gibbs showed that those processes could be accounted for by Maxwell's equations without any special assumptions about the microscopic structure of matter or about the nature of the medium in which electromagnetic waves were supposed to propagate (the so-called luminiferous ether).

[89] Even though it had been immediately embraced by Maxwell, Gibbs's graphical formulation of the laws of thermodynamics came into widespread use only in the mid 20th century, with the work of László Tisza and Herbert Callen.

[90] According to James Gerald Crowther, in his later years [Gibbs] was a tall, dignified gentleman, with a healthy stride and ruddy complexion, performing his share of household chores, approachable and kind (if unintelligible) to students.

He lived out his quiet life at Yale, deeply admired by a few able students but making no immediate impress on American science commensurate with his genius.On the other hand, Gibbs did receive the major honors then possible for an academic scientist in the US.

The Royal Society further honored Gibbs in 1901 with the Copley Medal, then regarded as the highest international award in the natural sciences,[3] noting that he had been "the first to apply the second law of thermodynamics to the exhaustive discussion of the relation between chemical, electrical and thermal energy and capacity for external work.

[96] That Gibbs succeeded in interesting his European correspondents in his work is demonstrated by the fact that his monograph "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances" was translated into German (then the leading language for chemistry) by Wilhelm Ostwald in 1892 and into French by Henri Louis Le Châtelier in 1899.

During Gibbs's lifetime, his phase rule was experimentally validated by Dutch chemist H. W. Bakhuis Roozeboom, who showed how to apply it in a variety of situations, thereby assuring it of widespread use.

[102] Gibbs's early papers on the use of graphical methods in thermodynamics reflect a powerfully original understanding of what mathematicians would later call "convex analysis",[103] including ideas that, according to Barry Simon, "lay dormant for about seventy-five years".

The publication in 1901 of E. B. Wilson's textbook Vector Analysis, based on Gibbs's lectures at Yale, did much to propagate the use of vectorial methods and notation in both mathematics and theoretical physics, definitively displacing the quaternions that had until then been dominant in the scientific literature.

[106] De Forest credited Gibbs's influence for the realization "that the leaders in electrical development would be those who pursued the higher theory of waves and oscillations and the transmission by these means of intelligence and power.

"[109] Mathematician Norbert Wiener cited Gibbs's use of probability in the formulation of statistical mechanics as "the first great revolution of twentieth century physics" and as a major influence on his conception of cybernetics.

Van Name had withheld the family papers from her and, after her book was published in 1942 to positive literary but mixed scientific reviews, he tried to encourage Gibbs's former students to produce a more technically oriented biography.

[136] In 2005, the United States Postal Service issued the American Scientists commemorative postage stamp series designed by artist Victor Stabin, depicting Gibbs, John von Neumann, Barbara McClintock, and Richard Feynman.

[137] Kenneth R. Jolls, a professor of chemical engineering at Iowa State University and an expert on graphical methods in thermodynamics, consulted on the design of the stamp honoring Gibbs.