Magic (supernatural)

[8] During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Western intellectuals perceived the practice of magic to be a sign of a primitive mentality and also commonly attributed it to marginalised groups of people.

[13] During the late-sixth and early-fifth centuries BCE, the term goetia found its way into ancient Greek, where it was used with negative connotations to apply to rites that were regarded as fraudulent, unconventional, and dangerous;[14] in particular they dedicate themselves to the evocation and invocation of daimons (lesser divinities or spirits) to control and acquire powers.

An alternative approach, associated with the sociologist Marcel Mauss (1872–1950) and his uncle Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), employs the term to describe private rites and ceremonies and contrasts it with religion, which it defines as a communal and organised activity.

They argued that the label drew arbitrary lines between similar beliefs and practices that were alternatively considered religious, and that it constituted ethnocentric to apply the connotations of magic—rooted in Western and Christian history—to other cultures.

[33] The conceptual link between women and magic in Western culture may be because many of the activities regarded as magical—from rites to encourage fertility to potions to induce abortions—were associated with the female sphere.

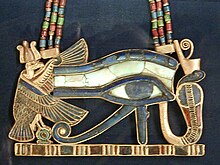

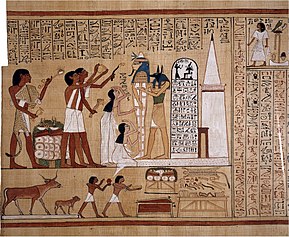

[65] Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of heka underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

[69] The interior walls of the pyramid of Unas, the final pharaoh of the Egyptian Fifth Dynasty, are covered in hundreds of magical spells and inscriptions, running from floor to ceiling in vertical columns.

[73] In the Mosaic Law, practices such as witchcraft (Biblical Hebrew: קְסָמִ֔ים), being a soothsayer (מְעוֹנֵ֥ן) or a sorcerer (וּמְכַשֵּֽׁף) or one who conjures spells (וְחֹבֵ֖ר חָ֑בֶר) or one who calls up the dead (וְדֹרֵ֖שׁ אֶל־הַמֵּתִֽים) are specifically forbidden as abominations to the Lord.

It was considered permitted white magic by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiritual source from qlippothic realms of evil if performed under circumstances that were holy (Q-D-Š) and pure (Biblical Hebrew: טומאה וטהרה, romanized: tvmh vthrh[76]).

[14] In Sophocles' play, for example, the character Oedipus derogatorily refers to the seer Tiresius as a magos—in this context meaning something akin to quack or charlatan—reflecting how this epithet was no longer reserved only for Persians.

Since the last decade of the century, however, recognising the ubiquity and respectability of acts such as katadesmoi (binding spells), described as magic by modern and ancient observers alike, scholars have been compelled to abandon this viewpoint.

[88]: 96 These qualities, and their perceived deviation from inherently mutable cultural constructs of normality, most clearly delineate ancient magic from the religious rituals of which they form a part.

[92] They contain early instances of: The practice of magic was banned in the late Roman world, and the Codex Theodosianus (438 AD) states:[95] If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician ... should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank.Magic practices such as divination, interpretation of omens, sorcery, and use of charms had been specifically forbidden in Mosaic Law[96] and condemned in Biblical histories of the kings.

[101] For early Christian writers like Augustine of Hippo, magic did not merely constitute fraudulent and unsanctioned ritual practices, but was the very opposite of religion because it relied upon cooperation from demons, the henchmen of Satan.

[104] The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: sorcière in French, Hexe in German, strega in Italian, and bruja in Spanish.

[114] One societal force in the Middle Ages more powerful than the singular commoner, the Christian Church, rejected magic as a whole because it was viewed as a means of tampering with the natural world in a supernatural manner associated with the biblical verses of Deuteronomy 18:9–12.

Another Arab Muslim author fundamental to the developments of medieval and Renaissance European magic was Ahmad al-Buni, with his books such as the Shams al-Ma'arif which deal above all with the evocation and invocation of spirits or jinn to control them, obtain powers and make wishes come true.

[86] According to the historian Richard Kieckhefer, the concept of magia naturalis took "firm hold in European culture" during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries,[126] attracting the interest of natural philosophers of various theoretical orientations, including Aristotelians, Neoplatonists, and Hermeticists.

[131] At the same time as magia naturalis was attracting interest and was largely tolerated, Europe saw an active persecution of accused witches believed to be guilty of maleficia.

[127] Reflecting the term's continued negative associations, Protestants often sought to denigrate Roman Catholic sacramental and devotional practices as being magical rather than religious.

The Arabian cleric Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab—founder of Wahhabism—for instance condemned a range of customs and practices such as divination and the veneration of spirits as sihr, which he in turn claimed was a form of shirk, the sin of idolatry.

In Hasidic doctrine, the tzaddik channels Divine spiritual and physical bounty to his followers by altering the Will of God (uncovering a deeper concealed Will) through his own deveikut and self-nullification.

Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639), an Italian philosopher, blended Christianity with mysticism in works like The City of the Sun, envisioning an ideal society governed by divine principles.

[148] In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, folklorists examined rural communities across Europe in search of magical practices, which at the time they typically understood as survivals of ancient belief systems.

[151] The scholarly application of magic as a sui generis category that can be applied to any socio-cultural context was linked with the promotion of modernity to both Western and non-Western audiences.

[158] The adoption of the term magic by modern occultists can in some instances be a deliberate attempt to champion those areas of Western society which have traditionally been marginalised as a means of subverting dominant systems of power.

[168] According with scholar of religion Michael Stausberg the phenomenon of people applying the concept of magic to refer to themselves and their own practices and beliefs goes as far back as late antiquity.

[175] Randall Styers noted that attempting to define magic represents "an act of demarcation" by which it is juxtaposed against "other social practices and modes of knowledge" such as religion and science.

[146] These repeated attempts to define magic resonated with broader social concerns,[8] and the pliability of the concept has allowed it to be "readily adaptable as a polemical and ideological tool".

"[212] Durkheim expressed the view that "there is something inherently anti-religious about the maneuvers of the magician",[205] and that a belief in magic "does not result in binding together those who adhere to it, nor in uniting them into a group leading a common life.