Color book

Especially in wartime or times of crisis, color books have been used as a form of white propaganda to justify governmental action, or to assign blame to foreign actors.

The choice of what documents to include, how to present them, and even what order to list them, can make the book tantamount to government-issued propaganda.

[10] In theory, their purpose was to give Parliament the info it needed (and sometimes demanded) to provide a basis for judgment on foreign affairs.

This lack of date would sometimes become problematic later for historians attempting to follow the historical record, and depended on further research to sort it out.

[11] Robert Stewart (Lord Castelreagh (1812–1822)) was the pivot point between the early years when the government might refuse to publish certain papers, and the later period when it was not able to do that anymore.

Henry Templeton (Lord Palmerston three incumbencies in the 1830s and 1840s) was unable to refuse the demands of the House of Commons, as Canning had done.

Later, when he rose to Prime Minister, Palmerston embodied the "Golden Age" of Blue Books, publishing a large number of them, especially during the Russell Foreign Ministry incumbency (1859–1865).

[11] Around the close of the century and beginning of the next, there was less disclosure of documents and less pressure from MPs and the public, and ministers became more restrained and secretive, for example with Sir Edward Grey, in the run-up to World War I. Penson & Temperley said, "As Parliament became more democratic its control over foreign policy declined, and, while Blue Books on domestic affairs expanded and multiplied at the end of the nineteenth century, those on foreign affairs lessened both in number and in interest.

[16] The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, led to a month of diplomatic maneuvering between Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France and Britain, called the July Crisis.

Austria-Hungary correctly believed that Serbian officials were involved in the assassination[18] and on 23 July sent Serbia an ultimatum intended to provoke a war.

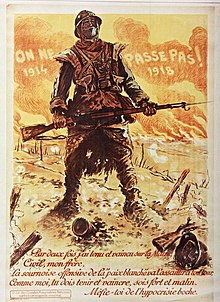

[9] World War I color books attempted to cast the issuing country in a good light, and enemy countries in a poor light via numerous means including omission, selective inclusion, changes in the sequence of (undated) documents presented in order to imply certain documents appeared earlier or later than they actually did, or outright falsification.

It appeared later in an expanded, and somewhat different version, and included an introduction and reports from parliamentary sessions in the beginning of August under the title, Great Britain and the European Crisis.

Although incomplete (e.g., files on the English promises of aid to France, and on German concessions and proposals are not included), it is the richest of the color books and "despite its gaps, constitutes a true treasure trove of historical insights into the great crisis".

[23][34][page needed] The British institution of political blue books with official publications of diplomatic documents found its way to Germany relatively late.

[39] The French Yellow Book (Livre Jaune), completed after three months of work, contained 164 documents and came out on 1 December 1914.

Historians who gained access to previously unpublished French material were able to use it in their report to the Senate entitled "Origins and responsibilities for the Great War"[d] as did ex-President Raymond Poincaré.

The conclusion set forth in the report of the 1919 French Peace Commission is illustrative of the two-pronged goals of blaming their opponents while justifying their own actions, as laid out in two sentences: The war was premeditated by the Central Powers, as well as by their Allies Turkey and Bulgaria, and is the result of acts deliberately committed with the intention of making it inevitable.Germany, in concordance with Austria-Hungary, worked deliberately to have the many conciliatory proposals of the Entente Powers set aside, and their efforts to avoid war nullified.

In her essay for the April 1937 issue of Foreign Affairs, Bernadotte E. Schmitt examined recently published diplomatic correspondence in the Documents Diplomatiques Français[42][43] and compared it to the documents in the French Yellow Book published in 1914, concluding that the Yellow Book "was neither complete nor entirely reliable" and went into some detail in examining documents either missing from the Yellow Book, or presented out of order to confuse or mislead the sequence in which events occurred.

On the other hand, the French will be able to find in them a justification of the policy they pursued in July 1914; and in spite of Herr Hitler's recent declaration repudiating Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, they will continue, on the basis of these documents, to hold Germany primarily responsible for the Great War.

[f] Simultaneously, the Austro-Hungarian government published a compact popular edition of the Red Book, which included an introduction, and translations into German of the few documents written in English or French.

Edmund von Mach's 1916 "Official Diplomatic Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the European War" gives the following introduction to the color books of World War I: In constitutionally governed countries it is customary for the Executive at important times to lay before the Representatives of the people "collected documents" containing the information on which the Government has shaped its foreign policy.

Following the previous customs of their respective countries the several Governments issued more or less exhaustive collections, and in each case were primarily guided by the desire to justify themselves before their own people.

The book is well printed, provided with indexes and cross references, and represents the most scholarly work done by any of the European governments.

The German White Book, on the other hand, contains few despatches, and these only as illustrations of points made in an exhaustive argument.