Yuan dynasty

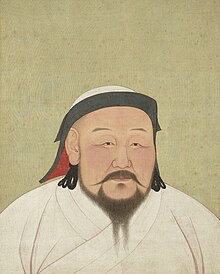

Although Genghis Khan's enthronement as Khagan in 1206 was described in Chinese as the Han-style title of Emperor[note 3][6] and the Mongol Empire had ruled territories including modern-day northern China for decades, it was not until 1271 that Kublai Khan officially proclaimed the dynasty in the traditional Han style,[13] and the conquest was not complete until 1279 when the Southern Song dynasty was defeated in the Battle of Yamen.

However, the Han-style dynastic name "Great Yuan" and the claim to Chinese political orthodoxy were meant for the entire Mongol Empire when the dynasty was proclaimed.

Under the reign of Genghis' third son, Ögedei Khan, the Mongols destroyed the weakened Jin dynasty in 1234, conquering most of northern China.

[34] Kublai built schools for Confucian scholars, issued paper money, revived Chinese rituals, and endorsed policies that stimulated agricultural and commercial growth.

[4] Kublai secured the northeast border in 1259 by installing the hostage prince Wonjong as the ruler of the Kingdom of Goryeo (Korea), making it a Mongol tributary state.

[58] He instituted the reforms proposed by his Chinese advisers by centralizing the bureaucracy, expanding the circulation of paper money, and maintaining the traditional monopolies on salt and iron.

[62] In 1271, Kublai formally claimed the Mandate of Heaven and declared that 1272 was the first year of the Great Yuan (大元) in the style of a traditional Chinese dynasty.

[67] Kublai evoked his public image as a sage emperor by following the rituals of Confucian propriety and ancestor veneration,[68] while simultaneously retaining his roots as a leader from the steppes.

[79]: 146 The Tusi chieftains and local tribe leaders and kingdoms in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan submitted to Yuan rule and were allowed to keep their titles.

He continued his father's policies to reform the government based on the Confucian principles, with the help of his newly appointed grand chancellor Baiju.

From the late 1340s onwards, people in the countryside suffered from frequent natural disasters such as droughts, floods and the resulting famines, and the government's lack of effective policy led to a loss of popular support.

In 1354, when Toghtogha led a large army to crush the Red Turban rebels, Toghon Temür suddenly dismissed him for fear of betrayal.

He fled north to Shangdu from Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing) in 1368 after the approach of the forces of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), founded by Zhu Yuanzhang in the south.

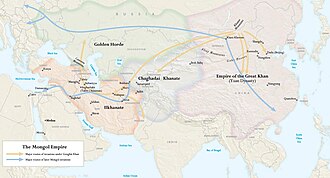

It had significantly eased trade and commerce across Asia until its decline; the communications between Yuan dynasty and its ally and subordinate in Persia, the Ilkhanate, encouraged this development.

Eastern crops such as carrots, turnips, new varieties of lemons, eggplants, and melons, high-quality granulated sugar, and cotton were all either introduced or successfully popularized during the Yuan dynasty.

Confucian governmental practices and examinations based on the Classics, which had fallen into disuse in north China during the period of disunity, were reinstated by the Yuan court, probably in the hope of maintaining order over Han society.

The most famous traveler of the period was the Venetian Marco Polo, whose account of his trip to "Cambaluc," the capital of the Great Khan, and of life there astounded the people of Europe.

The system of bureaucracy created by Kublai Khan reflected various cultures in the empire, including that of the Hans, Khitans, Jurchens, Mongols, and Tibetan Buddhists.

While the official terminology of the institutions may indicate the government structure was almost purely that of native Chinese dynasties, the Yuan bureaucracy actually consisted of a mix of elements from different cultures.

Nevertheless, such a civilian bureaucracy, with the Central Secretariat as the top institution that was (directly or indirectly) responsible for most other governmental agencies (such as the traditional Chinese-style Six Ministries), was created in China.

At various times another central government institution called the Department of State Affairs (尚書省; Shangshu Sheng) that mainly dealt with finance was established (such as during the reign of Külüg Khan or Emperor Wuzong), but was usually abandoned shortly afterwards.

Another example was the insignificance of the Ministry of War compared with native Chinese dynasties, as the real military authority in Yuan times resided in the Privy Council.

Chinese medical techniques such as acupuncture, moxibustion, pulse diagnosis, and various herbal drugs and elixirs were transmitted westward to the Middle East and the rest of the empire.

[131] In Chinese ceramics the period was one of expansion, with the great innovation the development in Jingdezhen ware of underglaze painted blue and white pottery.

[135] The average Mongol garrison family of the Yuan dynasty seems to have lived a life of decaying rural leisure, with income from the harvests of their Chinese tenants eaten up by costs of equipping and dispatching men for their tours of duty.

He set up a civilian administration to rule, built a capital within China, supported Chinese religions and culture, and devised suitable economic and political institutions for the court.

[148]: 255 After the Mongol conquest of Central Asia by Genghis Khan, foreigners were chosen as administrators of gardens and fields in Samarqand while co-management with Chinese and Khitans was required since Muslims were not allowed to manage without them.

"[157] However, ordinary Mongol families fell into extreme poverty in both Mongolia and China proper, and elite positions were increasingly penetrated by ethnic Han.

[158][159]: 467 Despite the high position given to Muslims, some policies of the Yuan emperors severely discriminated against them, restricting Halal slaughter and other Islamic practices like circumcision, as well as Kosher butchering for Jews, forcing them to eat food the Mongol way.

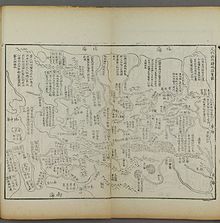

The Central Region, consisting of present-day Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi, the south-eastern part of present-day Inner Mongolia and the Henan areas to the north of the Yellow River, was considered the most important region of the dynasty and directly governed by the Central Secretariat (or Zhongshu Sheng, 中書省) at Khanbaliq (modern Beijing); similarly, another top-level administrative department called the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Chinese: 宣政院; pinyin: Xuānzhèng Yuàn) held administrative rule over the whole of modern-day Tibet and a part of Sichuan, Qinghai and Kashmir.

)

appears on all the territory.

[

75

]

)

appears on all the territory.

[

75

]