ATP synthase

This electrochemical gradient is generated by the electron transport chain and allows cells to store energy in ATP for later use.

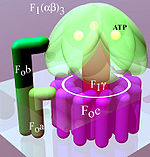

An F-ATPase consists of two main subunits, FO and F1, which has a rotational motor mechanism allowing for ATP production.

The ring has a tetrameric shape with a helix-loop-helix protein that goes through conformational changes when protonated and deprotonated, pushing neighboring subunits to rotate, causing the spinning of FO which then also affects conformation of F1, resulting in switching of states of alpha and beta subunits.

This part of the enzyme is located in the mitochondrial inner membrane and couples proton translocation to the rotation that causes ATP synthesis in the F1 region.

[12] An atomic model for the dimeric yeast FO region was determined by cryo-EM at an overall resolution of 3.6 Å.

[13] In the 1960s through the 1970s, Paul Boyer, a UCLA Professor, developed the binding change, or flip-flop, mechanism theory, which postulated that ATP synthesis is dependent on a conformational change in ATP synthase generated by rotation of the gamma subunit.

The research group of John E. Walker, then at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, crystallized the F1 catalytic-domain of ATP synthase.

According to the current model of ATP synthesis (known as the alternating catalytic model), the transmembrane potential created by (H+) proton cations supplied by the electron transport chain, drives the (H+) proton cations from the intermembrane space through the membrane via the FO region of ATP synthase.

The c-ring is tightly attached to the asymmetric central stalk (consisting primarily of the gamma subunit), causing it to rotate within the alpha3beta3 of F1 causing the 3 catalytic nucleotide binding sites to go through a series of conformational changes that lead to ATP synthesis.

The structure of the intact ATP synthase is currently known at low-resolution from electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) studies of the complex.

The cryo-EM model of ATP synthase suggests that the peripheral stalk is a flexible structure that wraps around the complex as it joins F1 to FO.

Under the right conditions, the enzyme reaction can also be carried out in reverse, with ATP hydrolysis driving proton pumping across the membrane.

The binding change mechanism involves the active site of a β subunit's cycling between three states.

[14] In the "loose" state, ADP and phosphate enter the active site; in the adjacent diagram, this is shown in pink.

Large-enough quantities of ATP cause it to create a transmembrane proton gradient, this is used by fermenting bacteria that do not have an electron transport chain, but rather hydrolyze ATP to make a proton gradient, which they use to drive flagella and the transport of nutrients into the cell.

[16][17] This association appears to have occurred early in evolutionary history, because essentially the same structure and activity of ATP synthase enzymes are present in all kingdoms of life.

[18][20][21] The α3β3 hexamer of the F1 region shows significant structural similarity to hexameric DNA helicases; both form a ring with 3-fold rotational symmetry with a central pore.

[21] The modular evolution theory for the origin of ATP synthase suggests that two subunits with independent function, a DNA helicase with ATPase activity and a H+ motor, were able to bind, and the rotation of the motor drove the ATPase activity of the helicase in reverse.

[16][22] This complex then evolved greater efficiency and eventually developed into today's intricate ATP synthases.

However, in chloroplasts, the proton motive force is generated not by respiratory electron transport chain but by primary photosynthetic proteins.