Alba Mons

The low areas between the ridges (particularly along the volcano's northern flank) show a branching pattern of shallow gullies and channels (valley networks) that likely formed by water runoff.

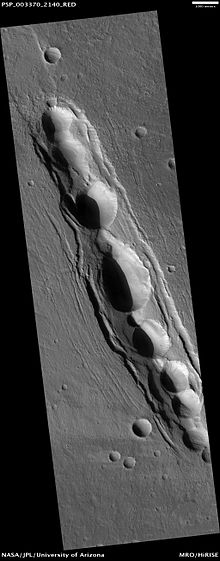

The southern part of Alba Mons is built on a broad, north–south topographic ridge that corresponds to the fractured, Noachian-aged terrain of Ceraunius Fossae[12] (pictured left).

Alba's size and low profile makes it a difficult structure to study visually, as much of the volcano's relief is indiscernible in orbital photographs.

Using MOLA data, planetary scientists are able to study subtle details of the volcano's shape and topography that were invisible in images from earlier spacecraft such as Viking.

[6] The crest and upper flanks of the edifice are cut by a partial ring of graben that are part of the Alba and Tantalus Fossae fracture system.

Inside the ring of graben is an annulus of very low and in places reversed slopes[6] that forms a plateau on top of which lies a central dome 350 km (220 mi) across capped by a nested caldera complex.

[25] Thus, the central edifice of Alba Mons resembles a partially collapsed shield volcano with a smaller, summit dome sitting on top (pictured right).

[33] Alba Mons is one of several areas on the planet that may contain thick deposits of near-surface ice preserved from an earlier epoch (1 to 10 million years ago), when Mars’ axial tilt (obliquity) was higher and mountain glaciers existed at mid-latitudes and tropics.

[35] The mineral composition of rocks making up Alba Mons is difficult to determine from orbital reflectance spectrometry because of the predominance of surface dust throughout the region.

This instrument has allowed scientists to determine the distribution of hydrogen (H), silicon (Si), iron (Fe), chlorine (Cl), thorium (Th) and potassium (K) in the shallow subsurface.

The thick mantle of dust obscures the underlying bedrock, probably making in situ rock samples hard to come by and thus reducing the site's scientific value.

Ironically, the summit region was originally considered a prime backup landing site for the Viking 2 lander because the area appeared so smooth in Mariner 9 images taken in the early 1970s.

[38] Most appear to originate near the Alba and Tantalus Fossae fracture ring, but the actual vents for the sheet flows are not visible and may have been buried by their own products.

Flat-topped ridges with indistinct margins and rugged surfaces,[10][37] interpreted as lava flows, are common along Alba's lower flanks and become less sharp in appearance with increasing distance from the edifice.

[43] Since the late 1980s, some researchers have suspected that Alba Mons eruptions included a significant amount of pyroclastics (and therefore explosive activity) during early phases of its development.

An alternative explanation for the valley networks on the north side of the volcano is that they were produced through sapping or melting of ice-rich dust deposited during a relatively recent, Amazonian-aged glacial epoch.

[12][48] In summary, current geologic analysis of Alba Mons suggests that the volcano was built by lavas with rheological properties similar to basalts.

[49] If early explosive activity happened at Alba Mons, the evidence (in the form of extensive ash deposits) is largely buried by younger basaltic lavas.

In theory they should appear as deep fissures with sharp V-shaped profiles, but in practice they are often difficult to distinguish from graben because their interiors rapidly fill with talus from the surrounding walls to produce relatively flat, graben-like floors.

[51] South of the volcano is a broad region of intensely fractured terrain called Ceraunius Fossae, which consists of roughly parallel arrays of narrow, north–south oriented faults.

[59] The northern slopes of Alba Mons contain numerous branching channel systems or valley networks that superficially resemble drainage features produced on Earth by rainfall.

This fact presents a problem for researchers who propose that valley networks were carved by rainfall runoff during an early, warm and wet period of Martian history.

[60] If the climate conditions changed billions of years ago into today's cold and dry Mars (where rainfall is impossible), how does one explain the younger valleys on Alba Mons?

[63] It seems likely that the valleys on Alba Mons formed as a result of transient erosional processes, possibly related to snow or ice deposits melting during volcanic activity,[63][64] or to short-lived periods of global climate change.

Using crater counting and basic principles of stratigraphy, such as superposition and cross-cutting relationships, geologists have been able to reconstruct much of Alba's geologic and tectonic history.

Most of the constructional volcanic activity at Alba is believed to have occurred within a relatively brief time interval (about 400 million years) of Mars history, spanning mostly the late Hesperian to very early Amazonian epochs.

This unit is characterized by sets of low, flat-topped ridges that form a radial pattern extending for hundreds of kilometers to the west, north, and northeast of the main edifice.

[66] Thus, the earliest phase of volcanic activity at Alba Mons probably involved massive effusive eruptions of low viscosity lavas that formed the volcano's broad, flat apron.

[12][14] The middle unit, which is early Amazonian in age, makes up the flanks of the main Alba edifice and records a time of more focused effusive activity consisting of long tube- and channel-fed flows.

Much later, between about 1,000 and 500 million years ago, a final stage of faulting occurred that may have been related to dike emplacement and the formation of pit crater chains.