Alcohol (chemistry)

In chemistry, an alcohol (from Arabic al-kuḥl 'the kohl'),[2] is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl (−OH) functional group bound to a saturated carbon atom.

[5] However, this did not immediately lead to the isolation of alcohol, even despite the development of more advanced distillation techniques in second- and third-century Roman Egypt.

[8] In the twelfth century, recipes for the production of aqua ardens ("burning water", i.e., alcohol) by distilling wine with salt started to appear in a number of Latin works, and by the end of the thirteenth century, it had become a widely known substance among Western European chemists.

The second part of the word (kuḥl) has several antecedents in Semitic languages, ultimately deriving from the Akkadian 𒎎𒋆𒁉𒍣𒁕 (guḫlum), meaning stibnite or antimony.

[13] Like its antecedents in Arabic and older languages, the term alcohol was originally used for the very fine powder produced by the sublimation of the natural mineral stibnite to form antimony trisulfide Sb2S3.

Later the meaning of alcohol was extended to distilled substances in general, and then narrowed again to ethanol, when "spirits" was a synonym for hard liquor.

[15] Bartholomew Traheron, in his 1543 translation of John of Vigo, introduces the word as a term used by "barbarous" authors for "fine powder."

Vigo wrote: "the barbarous auctours use alcohol, or (as I fynde it sometymes wryten) alcofoll, for moost fine poudre.

The word's meaning became restricted to "spirit of wine" (the chemical known today as ethanol) in the 18th century and was extended to the class of substances so-called as "alcohols" in modern chemistry after 1850.

However, some compounds that contain hydroxyl functional groups have trivial names that do not include the suffix -ol or the prefix hydroxy-, e.g. the sugars glucose and sucrose.

If a higher priority group is present (such as an aldehyde, ketone, or carboxylic acid), then the prefix hydroxy-is used,[19] e.g., as in 1-hydroxy-2-propanone (CH3C(O)CH2OH).

As described under systematic naming, if another group on the molecule takes priority, the alcohol moiety is often indicated using the "hydroxy-" prefix.

Because of hydrogen bonding, alcohols tend to have higher boiling points than comparable hydrocarbons and ethers.

[32] Many other alcohols are pervasive in organisms, as manifested in other sugars such as fructose and sucrose, in polyols such as glycerol, and in some amino acids such as serine.

Hydroxylation is the means by which the body processes many poisons, converting lipophilic compounds into hydrophilic derivatives that are more readily excreted.

Some low molecular weight alcohols of industrial importance are produced by the addition of water to alkenes.

The bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum can feed on cellulose (also an alcohol) to produce butanol on an industrial scale.

[34] Primary alkyl halides react with aqueous NaOH or KOH to give alcohols in nucleophilic aliphatic substitution.

Aldehydes or ketones are reduced with sodium borohydride or lithium aluminium hydride (after an acidic workup).

As a consequence, alkoxides (and hydroxide) are powerful bases and nucleophiles (e.g., for the Williamson ether synthesis) in this solvent.

In particular, RO− or HO− in DMSO can be used to generate significant equilibrium concentrations of acetylide ions through the deprotonation of alkynes (see Favorskii reaction).

For example, with methanol: Upon treatment with strong acids, alcohols undergo the E1 elimination reaction to produce alkenes.

The reaction, in general, obeys Zaitsev's Rule, which states that the most stable (usually the most substituted) alkene is formed.

This is a diagram of acid catalyzed dehydration of ethanol to produce ethylene: A more controlled elimination reaction requires the formation of the xanthate ester.

When treated with acid, these alcohols lose water to give stable carbocations, which are commercial dyes.

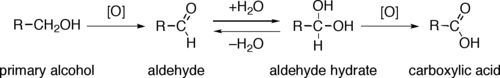

The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids can be carried out using potassium permanganate or the Jones reagent.