Abolitionism in the United States

At the time, Native Americans in the region were hosting raids against lower-class settlers encroaching on their land after the Third Powhatan War (1644–1646), which left many white and black indentured servants and slaves without a sense of protection from their government.

[12] Led by Nathaniel Bacon, the unification that occurred between the white lower class and blacks during this rebellion was perceived as dangerous and thus was quashed with the implementation of the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705.

His motivations included tactical defense against Spanish collusion with runaway slaves, and prevention of Georgia's largely reformed criminal population from replicating South Carolina's planter class structure.

The runaway slaves involved in the revolt intended to reach Spanish-controlled Florida to attain freedom, but their plans were thwarted by white colonists in Charlestown, South Carolina.

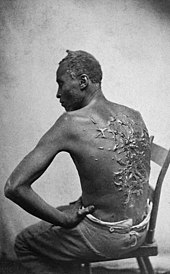

The institution remained solid in the South, and that region's customs and social beliefs evolved into a strident defense of slavery in response to the rise of a growing anti-slavery stance in the North.

Mainstream opinion changed from gradual emancipation and resettlement of freed blacks in Africa, sometimes a condition of their manumission, to immediatism: freeing all the slaves immediately and sorting out the problems later.

As it was put by Amos Adams Lawrence, who witnessed the capture and return to slavery of Anthony Burns, "we went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and waked up stark mad Abolitionists.

Historians traditionally distinguish between moderate anti-slavery reformers or gradualists, who concentrated on stopping the spread of slavery, and radical abolitionists or immediatists, whose demands for unconditional emancipation often merged with a concern for Black civil rights.

The artisan republicanism of Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright stood in stark contrast to the politics of prominent elite abolitionists such as industrialist Arthur Tappan and his evangelist brother Lewis.

"[71]: 106–107 Both Garrison's newspaper The Liberator and his book Thoughts on African Colonization (1832) arrived shortly after publication at Western Reserve College, in Hudson, Ohio, which was briefly the center of abolitionist discourse in the United States.

In 1854, Garrison wrote: I am a believer in that portion of the Declaration of American Independence in which it is set forth, as among self-evident truths, "that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

I will not be a liar, a poltroon, or a hypocrite, to accommodate any party, to gratify any sect, to escape any odium or peril, to save any interest, to preserve any institution, or to promote any object.

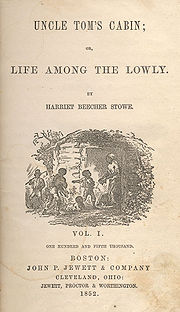

Outraged by the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 (which made the escape narrative part of everyday news), Stowe emphasized the horrors that abolitionists had long claimed about slavery.

"[87] According to historian George M. Fredrickson, "it would not be difficult to make a case for The Impending Crisis as the most important single book, in terms of its political impact, that has ever been published in the United States.

While slavery was fading away in the cities and border states, it remained strong in plantation areas that grew cash crops such as cotton, sugar, rice, tobacco or hemp.

The white abolitionist movement in the North was led by social reformers, especially William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society, and writers such as John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

[113]) It is true that beginning with the independent Republic of Vermont in 1777, all states north of the Ohio River and the Mason–Dixon line that separated Pennsylvania from Maryland passed laws that abolished slavery, although in some cases this did not apply to existing slaves, only their future offspring.

These included the first abolition laws in the entire New World:[46] the Massachusetts Constitution, adopted in 1780, declared all men to have rights, making slavery unenforceable, and it disappeared through the individual actions of both masters and slaves.

[134] The North felt threatened as well, for as Eric Foner concludes, "northerners came to view slavery as the very antithesis of the good society, as well as a threat to their own fundamental values and interests".

Effingham Capron, a cotton and textile scion, who attended the Quaker meeting where Abby Kelley Foster and her family were members, became a prominent abolitionist at the local, state, and national levels.

A more pragmatic group of abolitionists, such as Theodore Weld and Arthur Tappan, wanted immediate action, but were willing to support a program of gradual emancipation, with a long intermediate stage.

Despite a firm stand for the spiritual equality of black people, and the resounding condemnation of slavery by Pope Gregory XVI in his bull In supremo apostolatus issued in 1839, the American church continued in deeds, if not in public discourse, to avoid confrontation with slave-holding interests.

[145] William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newsletter the Liberator noted in 1847, "the Anti-Slavery cause cannot stop to estimate where the greatest indebtedness lies, but whenever the account is made up there can be no doubt that the efforts and sacrifices of the WOMEN, who helped it, will hold a most honorable and conspicuous position.

[151] Abby Kelley Foster, with a strong Quaker heritage, helped lead Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone into the abolition movement, and encouraged them to take on a role in political activism.

"From Maine to Missouri, from the Atlantic to the Gulf, crowds gathered to hear mayors and aldermen, bankers and lawyers, ministers and priests denounce the abolitionists as amalgamationists, dupes, fanatics, foreign agents, and incendiaries.

A majority of white Southerners, though by no means all, supported slavery; there was a growing feeling in favor of emancipation in North Carolina,[165] Maryland, Virginia, and Kentucky, until the panic resulting from Nat Turner's 1831 revolt put an end to it.

[183] The one time that Garrison defended Southern slave-owners was when he compared them with anti-abolitionist Northerners: I found [in the North] contempt more bitter, opposition more active, detraction more relentless, prejudice more stubborn, and apathy more frozen, than among slave owners themselves.

In the early 19th century, a variety of organizations were established that advocated relocation of black people from the United States, most prominently the American Colonization Society (ACS), founded in 1816.

Starting in the 1820s, the ACS and affiliated state societies assisted a few thousand free blacks to move to the newly established colonies in West Africa that were to form the Republic of Liberia.

"[191]: 11 [W]e gathered at Cleveland, where, by the grace of Judge Sterling, his law office was made free to us for the purpose, and there was opened a school of abolition, where, copying documents, with hints, discussions and suggestions, we spent two weeks in earnest and most profitable drill.