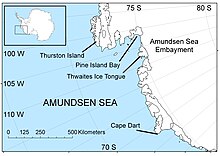

Amundsen Sea

Researchers reported that the flow of these glaciers increased starting in the mid-2000s; if they were to melt completely, global sea levels would rise by about 0.9–1.9 meters (3.0–6.2 feet).

[3] Measurements made by the British Antarctic Survey in 2005 showed that the ice discharge rate into the Amundsen Sea embayment was about 250 km3 per year.

[10] In January 2010, a modelling study suggested that the "tipping point" for Pine Island Glacier may have been passed in 1996, with a retreat of 200 kilometers (120 miles) possible by 2100, producing a corresponding 24 cm (0.79 ft) of sea level rise.

It was delineated from aerial photographs taken by United States Navy (USN) Operation HIGHJUMP in December 1946, and named by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names for the USS Pine Island, seaplane tender and flagship of the eastern task group of USN Operation HIGHJUMP which explored this area.

[16][17] A proposal from 2018 included building sills at the Thwaites' grounding line to either physically reinforce it, or to block some fraction of warm water flow.

[15][17] They also acknowledged that this intervention cannot prevent sea level rise from the increased ocean heat content, and would be ineffective in the long run without greenhouse gas emission reductions.

[15] In 2023, it was proposed that an installation of underwater curtains, made of a flexible material and anchored to the Amundsen Sea floor would be able to interrupt warm water flow.

[20][19][17] To achieve this, the curtains would have to be placed at a depth of around 600 metres (0.37 miles) (to avoid damage from icebergs which would be regularly drifting above) and be 80 km (50 mi) long.