Islamic architecture

[21][22][23] When the early Arab-Muslim conquests spread out from the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century and advanced across the Middle East and North Africa, new garrison cities were established in the conquered territories, such as Fustat in Egypt and Kufa in present-day Iraq.

[39] The Abbasids also built other capital cities, such as Samarra in the 9th century, which is now a major archeological site that has provided numerous insights into the evolution of Islamic art and architecture during this time.

[41][39] During the Abbasid Caliphate's golden years in the 8th and 9th centuries, its great power and unity allowed architectural fashions and innovations to spread quickly to other areas of the Islamic world under its influence.

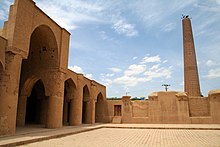

The Great Mosque of Samarra built by al-Mutawakkil measured 256 by 139 metres (840 by 456 ft), had a flat wooden roof supported by columns, and was decorated with marble panels and glass mosaics.

[51][52] The original Great Mosque of Cordoba was noted for its unique hypostyle hall with rows of double-tiered, two-coloured, arches, which were repeated and maintained in later extensions of the building.

The mosque was expanded multiple times, with the expansion by al-Hakam II (r. 961–976) introducing important aesthetic innovations such as interlacing arches and ribbed domes, which were imitated and elaborated in later monuments in the region.

The related Persian term, pishtaq, means the entrance portal (sometimes an iwan) projecting from the façade of a building, often decorated with calligraphy bands, glazed tilework, and geometric designs.

[73][74] Because of its long history of building and re-building, spanning the time from the Abbasids to the Qajar dynasty, and its excellent state of conservation, the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan provides an overview over the experiments Islamic architects conducted with complicated vaulting structures.

In his dialogue "Oeconomicus", Xenophon has Socrates relate the story of the Spartan general Lysander's visit to the Persian prince Cyrus the Younger, who shows the Greek his "Paradise at Sardis".

Early Islamic buildings in Iran featured "Persian" type capitals which included designs of bulls heads, while Mediterranean structures displayed a more classical influence.

[148] Donald Whitcomb argues that the early Muslim conquests initiated a conscious attempt to recreate specific morphological features characteristic of earlier western and southwestern Arabian cities.

[154] In a Muslim city, palaces and residences as well as public places like charitable or religious complexes (mosques, madrasas, and hospitals) and private living spaces rather coexist alongside each other.

The pinnacle of Ilkhanate architecture was reached with the construction of Uljaytu's mausoleum (1302–1312) in Soltaniyeh, Iran, which measures 50 m in height and 25 m in diameter, making it the 3rd largest and the tallest masonry dome ever erected.

[188] The extensive inscription bands of calligraphy and arabesque on most of the major buildings where carefully planned and executed by Ali Reza Abbasi, who was appointed head of the royal library and Master calligrapher at the Shah's court in 1598,[189] while Shaykh Bahai oversaw the construction projects.

[191] Under Zengid and Artuqid rule, cities like Mosul, Diyarbakir, Hasankeyf, and Mardin in Upper Mesopotamia (or al-Jazira in Arabic) became important centers of architectural development that had a long-term influence in the wider region.

[196][197] The city walls of Diyarbakir also feature several towers built by the Artuqids and decorated with a mix of calligraphic inscriptions and figurative images of animals and mythological creatures carved in stone.

The madrasas of Sivas and the Ince Minareli Medrese (c. 1265) in Konya are among the most notable examples, while the Great Mosque and Hospital complex of Divriği is distinguished by some of the most eclectic and extravagant stone-carving in the region.

[220] Mamluk architecture is distinguished in part by the construction of multi-functional buildings whose floor plans became increasingly creative and complex due to the limited available space in the city and the desire to make monuments visually dominant in their urban surroundings.

[250] For example, the Fatih Mosque in Istanbul was part of a very large külliye founded by Mehmed II, built between 1463 and 1470, which also included: a tabhane (guesthouse for travelers), an imaret (charitable kitchen), a darüşşifa (hospital), a caravanserai, a mektep (primary school), a library, a hammam (bathhouse), a cemetery with the founder's mausoleum, and eight madrasas along with their annexes.

[51][256][84][257] Major centers of this artistic development included the main capitals of the empires and Muslim states in the region's history, such as Cordoba, Kairouan, Fes, Marrakesh, Seville, Granada and Tlemcen.

[262] In Morocco, the largely Berber-inhabited rural valleys and oases of the Atlas and the south are marked by numerous kasbahs (fortresses) and ksour (fortified villages), typically flat-roofed structures made of rammed earth and decorated with local geometric motifs, as with the famous example of Ait Benhaddou.

[262][263][264] Likewise, southern Tunisia is dotted with hilltop ksour and multi-story fortified granaries (ghorfa), such as the examples in Medenine and Ksar Ouled Soltane, typically built with loose stone bound by a mortar of clay.

[275][277] The progress of Islamization in the region during the 14th and 15th centuries resulted in the emergence of a more distinctive Indo-Islamic style around this time, as exemplified by the monuments built under the Tughluq dynasty and other local states.

[286] The Deccan sultanates in the southern regions of the Indian subcontinent also developed their local Indo-Islamic Deccani architectural styles, exemplified by monuments such as the Charminar in Hyderabad (1591) and Gol Gumbaz in Bijapur (1656).

Two of the Hindu features adopted into Islam in the palace is the two types of gateways - the split portal (candi bentar) which provides access to the public audience pavilion and the lintel gate (paduraksa) which leads to the frontcourt.

They have tapering buttresses with cone-shaped summits, mosques have a large tower over the mihrab, and wooden stakes (toron) are often embedded in the walls – used for scaffolding but possibly also for some symbolic purpose.

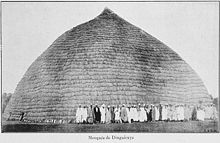

[307] In the Fouta Djallon region, in the Guinea Highlands, mosques were built with a traditional rectangular or square layout, but then covered by a huge conical thatched roof which protects from the rain.

This type of roof was an existing feature of the traditional circular huts inhabited by the locals, re-adapted to cover new rectangular mosques when the mostly Muslim Fula people settled the region in the 18th century.

It was built and modified in multiple phases, with the oldest surviving section dating possibly to the 11th century, to which was later added a courtyard with porticos of coral stone columns and a side chamber with the largest historic dome on the East African coast (5 meters in diameter).

Examples showing this are places such as the Marrakesh Menara Airport, the Islamic Cultural Center and Museum of Tolerance, Masjid Permata Qolbu, the concept for The Vanishing Mosque, and the Mazar-e-Quaid.