Area

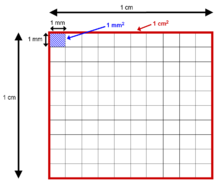

[2] In the International System of Units (SI), the standard unit of area is the square metre (written as m2), which is the area of a square whose sides are one metre long.

There are several well-known formulas for the areas of simple shapes such as triangles, rectangles, and circles.

[4] For shapes with curved boundary, calculus is usually required to compute the area.

Indeed, the problem of determining the area of plane figures was a major motivation for the historical development of calculus.

[1][6][7] Formulas for the surface areas of simple shapes were computed by the ancient Greeks, but computing the surface area of a more complicated shape usually requires multivariable calculus.

[10] In general, area in higher mathematics is seen as a special case of volume for two-dimensional regions.

"Area" can be defined as a function from a collection M of a special kinds of plane figures (termed measurable sets) to the set of real numbers, which satisfies the following properties:[11] It can be proved that such an area function actually exists.

Similarly: In addition, conversion factors include: There are several other common units for area.

The are was the original unit of area in the metric system, with: Though the are has fallen out of use, the hectare is still commonly used to measure land:[13] Other uncommon metric units of area include the tetrad, the hectad, and the myriad.

Each administrative division has its own area unit, some of them have same names, but with different values.

[14][15][16][17] Some traditional South Asian units that have fixed value: In the 5th century BCE, Hippocrates of Chios was the first to show that the area of a disk (the region enclosed by a circle) is proportional to the square of its diameter, as part of his quadrature of the lune of Hippocrates,[18] but did not identify the constant of proportionality.

Eudoxus of Cnidus, also in the 5th century BCE, also found that the area of a disk is proportional to its radius squared.

[19] Subsequently, Book I of Euclid's Elements dealt with equality of areas between two-dimensional figures.

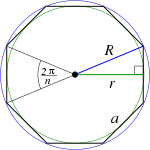

Archimedes approximated the value of π (and hence the area of a unit-radius circle) with his doubling method, in which he inscribed a regular triangle in a circle and noted its area, then doubled the number of sides to give a regular hexagon, then repeatedly doubled the number of sides as the polygon's area got closer and closer to that of the circle (and did the same with circumscribed polygons).

[21] In 300 BCE Greek mathematician Euclid proved that the area of a triangle is half that of a parallelogram with the same base and height in his book Elements of Geometry.

[22] In 499 Aryabhata, a great mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, expressed the area of a triangle as one-half the base times the height in the Aryabhatiya.

[23] In the 7th century CE, Brahmagupta developed a formula, now known as Brahmagupta's formula, for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a quadrilateral inscribed in a circle) in terms of its sides.

In 1842, the German mathematicians Carl Anton Bretschneider and Karl Georg Christian von Staudt independently found a formula, known as Bretschneider's formula, for the area of any quadrilateral.

The development of Cartesian coordinates by René Descartes in the 17th century allowed the development of the surveyor's formula for the area of any polygon with known vertex locations by Gauss in the 19th century.

(i=0, 1, ..., n-1) of whose n vertices are known, the area is given by the surveyor's formula:[25] where when i=n-1, then i+1 is expressed as modulus n and so refers to 0.

On the other hand, if geometry is developed before arithmetic, this formula can be used to define multiplication of real numbers.

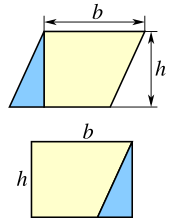

For an example, any parallelogram can be subdivided into a trapezoid and a right triangle, as shown in figure to the left.

If the triangle is moved to the other side of the trapezoid, then the resulting figure is a rectangle.

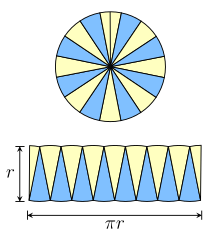

The height of this parallelogram is r, and the width is half the circumference of the circle, or πr.

To find the bounded area between two quadratic functions, we first subtract one from the other, writing the difference as

The general formula for the surface area of the graph of a continuously differentiable function

is a region in the xy-plane with the smooth boundary: An even more general formula for the area of the graph of a parametric surface in the vector form

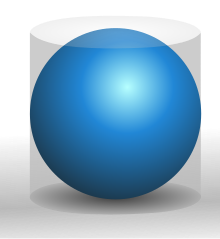

bottom) (rotation around the x-axis) The above calculations show how to find the areas of many common shapes.

[28] The isoperimetric inequality states that, for a closed curve of length L (so the region it encloses has perimeter L) and for area A of the region that it encloses, and equality holds if and only if the curve is a circle.

The question of the filling area of the Riemannian circle remains open.