Military history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

Although he campaigned for 31 years of his 35-year reign,[4] he failed to achieve or equal the conquests of his predecessor,[5] and his death led to another period of weakness in Assyrian rule.

It appears that years of costly battles followed by constant (and almost unstoppable) rebellions meant that it was a matter of time before Assyria ran out of troops.

The ruler of Lagash, Eanatum, was inspired by the god Ningirsu to attack the rival kingdom of Umma; the two were involved in minor skirmishes and raids along their respective borders.

[12] The 11th and 10th centuries BC were a dark age for the entire Near East, North Africa, Caucasus, Mediterranean and Balkan regions, with great upheavals and mass movements of people.

Assyria, with its stable monarchy and secure borders, was in a stronger position during this time than potential rivals such as Egypt, Babylonia, Elam, Phrygia, Urartu, Persia and Media.

However, military tactics mainly involved using troops raised from farmers who had finished planting their fields and so could campaign for the king until harvest time called for their attention again.

Professional soldiers were limited to a few bodyguards that protected the King and or other nobles and officials, but these would not have been deployed or wasted in battle unless the situation became urgent, as it later did.

Vassal states were in particular required to present troops as part of their tribute to the Assyrian king and in good time: failure to do so would have almost certainly been seen as an act of rebellion.

Following this was the King, the humble servant of Assur surrounded by his bodyguard with the support of the main chariot divisions and cavalry, the elite of the army.

[14] There were exceptions however, and as casualties mounted additional troops would not be unwelcome; Sargon II reports that he managed to incorporate 60 Israelite chariot teams into his army.

Engineers built fine stone pavements leading up to the grand cities of Assur and Nineveh, so as to impress foreigners with the wealth of Assyria.

The construction of roads and increased transport meant that goods would flow through the empire with greater ease, thus feeding the Assyrian war effort further.

[19] Traditionally, the Sumerians are credited for inventing the wheel sometime before 3000 BC, although there is increasing evidence to support an Indo-European origin in the Black Sea region of Ukraine (Wolchover, Scientific American, 2012).

[27] At the command of the god Ashur, the great Lord, I rushed upon the enemy like the approach of a hurricane...I put them to rout and turned them back.

However, they were also a strategy employed when time was not on their side: The harassed troops of Ashur, who had come a long way, very weary slow to respond, who had crossed and re-crossed sheer mountains innumerable, of great trouble for ascent and descent, their morale turned mutinous.

So vicious was the battle that the Urartian King abandoned his state officials, governors, 230 members of the royal family, many cavalry and infantry, and even the capital itself.

However, rivers would not stop a determined army, so attacking and destroying their enemies' ability to wage war was the best method of ensuring the survival of the Assyrians.

The primary aim was to establish a loyal power base; taxes, food and troops could be raised here as reliably as at their homeland, or at least that must have been the hope.

Furthermore, their presence would bring innumerable benefits: resistance to other conquerors, a counter to any rebellions by the natives and assisting the provincial Assyrian governors in ensuring that the vassal state was loyal to Assyria.

[32] The purposes of deportation included, but were not limited to:[citation needed] 1) Psychological warfare: the possibility of deportation would have terrorized the people; 2) Integration: a multi-ethnic population base in each region would have curbed nationalist sentiment, making the running of the Empire smoother; 3) Preservation of human resources: rather than being butchered, the people could serve as slave labor or as conscripts in the army.

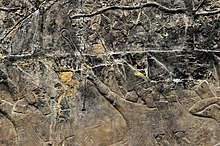

In one of his expeditions, Ashurnasirpal II described how he faced the rebels, in which they were being flayed, impaled, decapitated, or burned alive: I felled 3,000 of their fighting men with the sword.

They were so successful in their brutality in the northern cities of Syria in that many of the smaller settlements were immediately handed over to their troops, then they marched south in parallel of the Mediterranean.

[34] Other acts of brutality include: mutilating men to death, cutting off heads, arms, hands and lips and displaying them on the walls of conquered cities, hanging skulls and noses on the top of stakes, stacking or cutting corpses so that it could be fed to dogs and forcing people whose eyes were blinded to publicly roam so that natives would be demoralized.

A tablet unearthed in 1854 by Austen Henry Layard in Nineveh reveals Ashurbanipal as an "avenger", seeking retribution for the humiliations the Elamites had inflicted on the Mesopotamians over the centuries.

Raiders from all nations coveted the lands of the Assyrians: Scythians to the north, Syrians, Arameans and Cimmerians to the West, Elamites to the East and Babylonians to the south.

[5] As a result, in order to prevent chariots and cavalry from completely overwhelming these settlements, walls were constructed though often from mud or clay since stone was neither cheap, nor readily available.

In order to destroy the opponents, these cities had to be taken as well and so the Assyrians soon mastered siege warfare; Esarhaddon claims to have taken Memphis, the capital of Egypt in less than a day, demonstrating the ferocity and skill of Assyrian siege tactics at this point in time: I fought daily, without interruption against Taharqa, King of Egypt and Ethiopia, the one accursed by all the great gods.

Five times I hit him with the point of my arrows inflicting wounds from which he should not recover, and then I laid siege to Memphis his royal residence, and conquered it in half a day by means of mines, breaches and assault laddersSieges were costly in terms of manpower and more so if an assault was launched to take the city by force—the siege of Lachish cost the Assyrians at least 1,500 men found at a mass grave near Lachish.

Nonetheless, it is known that Assyrians always preferred to take a city by assault than to settle down for a blockade: the former method would be followed by extermination or deportation of the inhabitants and would therefore frighten the opponents of Assyria into surrendering as well.

I captured 46 towns... by consolidating ramps to bring up battering rams, by infantry attacks, mines, breaches and siege enginesSiege towers, even ones that could float were reported to have been in use whenever there was a wall facing a river.