Aztecs

[7] Client city-states paid taxes, not tribute[8] to the Aztec emperor, the Huey Tlatoani, in an economic strategy limiting communication and trade between outlying polities, making them dependent on the imperial center for the acquisition of luxury goods.

Important for knowledge of post-conquest Nahuas was the training of indigenous scribes to write alphabetic texts in Nahuatl, mainly for local purposes under Spanish colonial rule.

[17] In other contexts, Aztec may refer to all the various city-states and their peoples, who shared large parts of their ethnic history and cultural traits with the Mexica, Acolhua, and Tepanecs, and who often also used the Nahuatl language as a lingua franca.

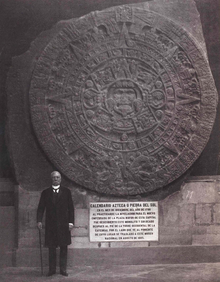

Alexander von Humboldt originated the modern usage of "Aztec" in 1810, as a collective term applied to all the people linked by trade, custom, religion, and language to the Mexica state and the Triple Alliance.

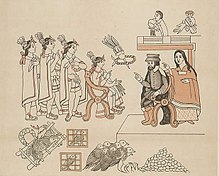

An important pictorial and alphabetic text produced in the early sixteenth century was Codex Mendoza, named after the first viceroy of Mexico and perhaps commissioned by him, to inform the Spanish crown about the political and economic structure of the Aztec empire.

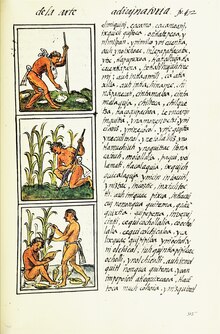

[27] An invaluable source of information about many aspects of Aztec religious thought, political and social structure, as well as the history of the Spanish conquest from the Mexica viewpoint is the Florentine Codex.

Produced between 1545 and 1576 in the form of an ethnographic encyclopedia written bilingually in Spanish and Nahuatl, by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and indigenous informants and scribes, it contains knowledge about many aspects of precolonial society from religion, calendrics, botany, zoology, trades and crafts and history.

An effective warrior, Moctezuma maintained the pace of conquest set by his predecessor and subjected large areas in Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, and even far south along the Pacific and Gulf coasts, conquering the province of Xoconochco in Chiapas.

[54] In 1517, Moctezuma received the first news of ships with strange warriors having landed on the Gulf Coast near Cempoallan and he dispatched messengers to greet them and find out what was happening, and he ordered his subjects in the area to keep him informed of any new arrivals.

As this shift in power became clear to Moctezuma's subjects, the Spaniards became increasingly unwelcome in the capital city, and, in June 1520, hostilities broke out, culminating in the massacre in the Great Temple, and a major uprising of the Mexica against the Spanish.

The pilli status was hereditary and ascribed certain privileges to its holders, such as the right to wear particularly fine garments and consume luxury goods, as well as to own land and direct corvee labor by commoners.

Some macehualtin were landless and worked directly for a lord (Nahuatl languages: mayehqueh), whereas the majority of commoners were organized into calpollis which gave them access to land and property.

In Tlaxcala and the Puebla valley, the altepetl was organized into teccalli units headed by a lord (Nahuatl languages: tecutli), who would hold sway over a territory and distribute rights to land among the commoners.

Particularly important for agricultural production in the valley was the construction of chinampas on the lake, artificial islands that allowed the conversion of the shallow waters into highly fertile gardens that could be cultivated year-round.

[82] The centerpiece of Tenochtitlan was the Templo Mayor, the Great Temple, a large stepped pyramid with a double staircase leading up to two twin shrines – one dedicated to Tlaloc, the other to Huitzilopochtli.

[83] Archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, in his essay Symbolism of the Templo Mayor, posits that the orientation of the temple is indicative of the totality of the vision the Mexica had of the universe (cosmovision).

[84][85] Other major Aztec cities were some of the previous city-state centers around the lake including Tenayuca, Azcapotzalco, Texcoco, Colhuacan, Tlacopan, Chapultepec, Coyoacan, Xochimilco, and Chalco.

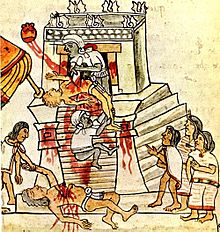

Public ritual practices could involve food, storytelling, and dance, as well as ceremonial warfare, the Mesoamerican ballgame, and human sacrifice, as a manner of payment for, or even effecting, the continuation of the days and the cycle of life.

In the 1970s, Michael Harner and Marvin Harris argued that the motivation behind human sacrifice among the Aztecs was the cannibalization of the sacrificial victims, depicted for example in Codex Magliabechiano.

Harner claimed that very high population pressure and an emphasis on maize agriculture, without domesticated herbivores, led to a deficiency of essential amino acids among the Aztecs.

[108][105] Today, many scholars point to ideological explanations of the practice, noting how the public spectacle of sacrificing warriors from conquered states was a major display of political power, supporting the claim of the ruling classes to divine authority.

After the conquest, codices with calendric or religious information were sought out and systematically destroyed by the church – whereas other types of painted books, particularly historical narratives, and tax lists continued to be produced.

[27] Karl Anton Nowotny, nevertheless considered that the Codex Borgia, painted in the area around Cholula and using a Mixtec style, was the "most significant work of art among the extant manuscripts".

[135] Although Aztec stone sculptures are now displayed in museums as unadorned rock, they were originally painted in vivid polychrome color, sometimes covered first with a base coat of plaster.

[135] An especially prized art form among the Aztecs was featherwork – the creation of intricate and colorful mosaics of feathers, and their use in garments as well as decoration on weaponry, war banners, and warrior suits.

[161] Even before Mexico achieved its independence, American-born Spaniards (criollos) drew on Aztec history to ground their search for symbols of local pride, separate from that of Spain.

Although the flag of the Mexican Republic had the symbol of the Aztecs as its central element, conservative elites were generally hostile to the current indigenous populations of Mexico or crediting them with a glorious pre-Hispanic history.

French Americanist Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg (1814–1874) asserted that "science in our own time has at last effectively studied and rehabilitated America and the Americans from the [previous] viewpoint of history and archeology.

[168] When the International Congress of Americanists was formed in Nancy, France in 1875, Mexican scholars became active participants, and Mexico City hosted the biennial multidisciplinary meeting six times, starting in 1895.

Through the spread of ancient Mesoamerican food elements, particularly plants, Nahuatl loan words (chocolate, tomato, chili, avocado, tamale, taco, pupusa, chipotle, pozole, atole) have been borrowed through Spanish into other languages around the world.