Catalan nationalism

Intellectually, modern Catalan nationalism can be said to have commenced as a political philosophy in the unsuccessful attempts to establish a federal state in Spain in the context of the First Republic (1873-1874).

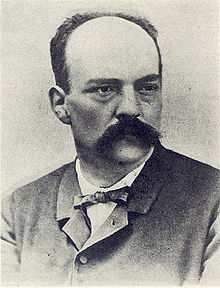

Valentí Almirall i Llozer and other intellectuals that participated in this process set up a new political ideology in the 19th century, to restore self-government, as well as to obtain recognition for the Catalan language.

During the conflict, John II, in the face of French aggression in the Pyrenees[3] "had his heir Ferdinand married to Isabella I of Castile, the heiress to the Castilian throne, in a bid to find outside allies" (Balcells 11).

At that point, however, de jure both the Castile and the states of the Crown of Aragon remained distinct entities, each keeping its own separate jurisdictions, institutions, parliaments and legislation.

Both support Pierre Vilar, who contends that in 13th and 14th centuries "the Catalan principality was perhaps the European country to which it would be the least inexact or risky to use such seemingly anachronistic terms as political and economic imperialism or 'nation-state'" (McRoberts 13).

The Catalan institutions and most of local population took sides and provided troops and resources for Archduke Charles, the pretender, who was arguably expected to maintain and modernize the legal status quo.

The Renaixença ("rebirth" or "renaissance") was a cultural, historical and literary movement that pursued, in the wake of European Romanticism, the recovery of the Catalans' own language and literature after a century of repression and radical political and economical changes.

It first appeared in the writings of Juan Cortada (1805–1868), Marti d'Eixalà (1807–1857) and his discipline, Francesco Javier Llorens y Barba, intellectuals who reinvigorated the literature on the Catalan national character.

Inspired by the ideas of Herder, Savigny and the entire Scottish School of Common Sense, they asked why the Catalans were different from other Spaniards — especially the Castilians (Conversi 1997: 15) For example, Cortada wanted to determine why, despite its poor natural environment, Catalonia was so much more successful economically than other parts of Spain.

At the same time it started to establish its first political programmes (e.g. Memorial of Wrongs Bases de Manresa, 1892), and to generate a wide cultural and association movement of a clearly nationalistic character.

In 1898, Spain lost its last colonial possessions in Cuba and the Philippines, a fact that not only created an important crisis of national confidence, but also gave an impulse to political Catalanism.

Unlike in the rest of Spain, the Industrial Revolution made some progress in Catalonia, whose pro-industry middle class strove to mechanize everything, from textiles and crafts to wineries.

As Stanley Payne observes: "The modern Catalan élite had played a major role in what there was of economic industrialization in the nineteenth century, and had tended to view Catalonia not as the antagonist but to some degree the leader of a freer, more prosperous Spain" (482).

Finally, in 1889, the pro-industrialist Lliga Regionalista managed to save the particular Catalan Civil Code, after a liberal attempt to homogenize the Spanish legal structures (Conversi 1997: 20).

Then, they also took great profits from Spain's neutrality in World War I, which allowed them to export to both sides, and the Spanish expansion in Morocco, which Catalan industrialists encouraged, since it was to become a fast growing market for them.

Also, by the early 20th century, Catalan businessmen had managed to gain control of the most profitable commerce between Spain and its American colonies and ex-colonies, namely Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Payne notes: "The main Catalanist party, the bourgeois Lliga, never sought separatism but rather a more discrete and distinctive place for a self-governing Catalonia within a more reformist and progressive Spain.

The Commonwealth developed an important infrastructure (like roads and phones) and promoted the culture (professional education, libraries, regulation of Catalan language, study of sciences) in order to modernize Catalonia.

Among the leaders of Acció Catalana founded in 1922 and chiefly supportive of liberal-democratic catalanism and a catalanisation process were Jaume Bofill, Antoni Rovira i Virgili and Lluís Nicolau d'Olwer.

The anti-Catalan measures taken by dictator Primo de Rivera led to further disappointment among Catalan conservatives, who initially trusted in him because of an earlier support of regionalism prior to his pronunciamiento in September 1923, and also further exacerbation of insurrectionary nationalists.

[8] In November 1926 Macià helmed an attempt of military invasion of Catalonia from France which would purposely lead to a civil uprising and the proclamation of the Catalan Republic; he was not able even to get past through the border.

In contrast, there is no significant political autonomy, nor recognition of the language in the historical Catalan territories belonging to France (Roussillon, in the French département of Pyrénées-Orientales).

In the 2017 Catalan regional election the nationalist parties that support the creation of an independent state (JuntsxCat, ERC and CUP) obtained a plurality of seats, but a minority of votes with less than 50%.

"[15] A law creating an independent republic—in the event that the referendum took place and there was a majority "yes" vote, without requiring a minimum turnout—was approved by the Catalan parliament in a session on 6 September 2017.

[19] On 7 September, the Catalan parliament passed a "transition law", to provide a legal framework pending the adoption of a new constitution, after similar protests and another walkout by opposition parties.

[25][26][27] The national government seized ballot papers and cell phones, threatened to fine people who manned polling stations up to €300,000, shut down web sites, and demanded that Google remove a voting location finder from the Android app store.

[43][44][45] Additionally, in early September the High Court of Justice of Catalonia had issued orders to the police to try to prevent it, including the detention of various persons responsible for its preparation.

[59][60][61] On the other hand, many voters who did not support Catalan independence did not turn out,[62] as the constitutional political parties asked citizens not to participate in what they considered an illegal referendum.

[73] The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra'ad Al, urged the Spanish government to prove all acts of violence that took place to prevent the referendum.

[76][77] Spanish Supreme Court judge Pablo Llarena stated Puigdemont ignored the repeated warnings he received about the escalation of violence if the referendum was held.