Lipid bilayer

Biological bilayers are usually composed of amphiphilic phospholipids that have a hydrophilic phosphate head and a hydrophobic tail consisting of two fatty acid chains.

Phospholipids with certain head groups can alter the surface chemistry of a bilayer and can, for example, serve as signals as well as "anchors" for other molecules in the membranes of cells.

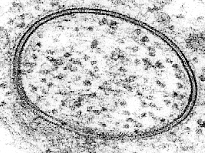

If a typical mammalian cell (diameter ~10 micrometers) were magnified to the size of a watermelon (~1 ft/30 cm), the lipid bilayer making up the plasma membrane would be about as thick as a piece of office paper.

These regions and their interactions with the surrounding water have been characterized over the past several decades with x-ray reflectometry,[6] neutron scattering,[7] and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques.

[9] In some cases, the hydrated region can extend much further, for instance in lipids with a large protein or long sugar chain grafted to the head.

Certain types of very small artificial vesicle will automatically make themselves slightly asymmetric, although the mechanism by which this asymmetry is generated is very different from that in cells.

[13] An example of this effect can be noted in everyday life as butter, which has a large percentage saturated fats, is solid at room temperature while vegetable oil, which is mostly unsaturated, is liquid.

[33] One particularly important component of many mixed phase systems is cholesterol, which modulates bilayer permeability, mechanical strength, and biochemical interactions.

[50][49][51] Electrical measurements are a straightforward way to characterize an important function of a bilayer: its ability to segregate and prevent the flow of ions in solution.

In conjunction with rapid freezing techniques, electron microscopy has also been used to study the mechanisms of inter- and intracellular transport, for instance in demonstrating that exocytotic vesicles are the means of chemical release at synapses.

Rather than using a beam of light or particles, a very small sharpened tip scans the surface by making physical contact with the bilayer and moving across it, like a record player needle.

AFM is a promising technique because it has the potential to image with nanometer resolution at room temperature and even under water or physiological buffer, conditions necessary for natural bilayer behavior.

[56] Another advantage is that AFM does not require fluorescent or isotopic labeling of the lipids, since the probe tip interacts mechanically with the bilayer surface.

In the previous example it was electrical bias, but other channels can be activated by binding a molecular agonist or through a conformational change in another nearby protein.

[71] This myth was however broken with the revelation that nanovesicles, popularly known as bacterial outer membrane vesicles, released by gram-negative microbes, translocate bacterial signal molecules to host or target cells[72] to carry out multiple processes in favour of the secreting microbe e.g., in host cell invasion[73] and microbe-environment interactions, in general.

[81] It is not surprising given this understanding of the forces involved that studies have shown that Ka varies strongly with osmotic pressure[82] but only weakly with tail length and unsaturation.

Addition of small hydrophilic molecules like sucrose into mixed lipid lamellar liposomes made from galactolipid-rich thylakoid membranes destabilises bilayers into the micellar phase.

Exocytosis, fertilization of an egg by sperm activation, and transport of waste products to the lysozome are a few of the many eukaryotic processes that rely on some form of fusion.

In fact, there is still an active debate regarding whether SNAREs are linked to early docking or participate later in the fusion process by facilitating hemifusion.

[94] The resulting “hybridoma” from this combination expresses a desired antibody as determined by the B-cell involved, but is immortalized due to the melanoma component.

It is believed that this phenomenon results from the energetically active edges formed during electroporation, which can act as the local defect point to nucleate stalk growth between two bilayers.

Among the most common model systems are:[96] To date, the most successful commercial application of lipid bilayers has been the use of liposomes for drug delivery, especially for cancer treatment.

[98] The most significant advance in this area was the grafting of polyethylene glycol (PEG) onto the liposome surface to produce “stealth” vesicles, which circulate over long times without immune or renal clearing.

Because tumors induce rapid and uncontrolled angiogenesis they are especially “leaky” and allow liposomes to exit the bloodstream at a much higher rate than normal tissue would.

work has been undertaken to graft antibodies or other molecular markers onto the liposome surface in the hope of actively binding them to a specific cell or tissue type.

These include Biacore (now GE Healthcare Life Sciences), which offers a disposable chip for utilizing lipid bilayers in studies of binding kinetics[103] and Nanion Inc., which has developed an automated patch clamping system.

[104] A supported lipid bilayer (SLB) as described above has achieved commercial success as a screening technique to measure the permeability of drugs.

[109] By the early twentieth century scientists had come to believe that cells are surrounded by a thin oil-like barrier,[110] but the structural nature of this membrane was not known.

Prof. Dr. Evert Gorter[112] (1881–1954) and F. Grendel of Leiden University approached the problem from a different perspective, spreading the erythrocyte lipids as a monolayer on a Langmuir-Blodgett trough.

By “painting” a solution of lipid in organic solvent across an aperture, Mueller and Rudin were able to create an artificial bilayer and determine that this exhibited lateral fluidity, high electrical resistance and self-healing in response to puncture,[117] all of which are properties of a natural cell membrane.