Celtic language decline in England

The influence and position of British Latin declined when the Roman economy and administrative structures collapsed in the early 5th century.

There is no serious doubt that Old English was brought to Britain primarily during the 5th and 6th centuries by settlers from what are now the Netherlands, north-western Germany, and southern Denmark who spoke various dialects of Germanic languages[10][11] and who came to be known as Anglo-Saxons.

Celtic languages continued to be spoken in other parts of the British Isles, such as Wales, Scotland, Ireland and Cornwall.

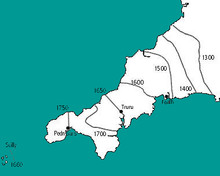

However, Kenneth Jackson combined historical information from texts like Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) with evidence for the linguistic origins of British river names to suggest the following chronology, which remains broadly accepted (see map): Although Cumbric, in the northern part of Area 3, seems to have died during the 11th century,[15] Cornish continued to thrive until the early modern period and retreated at only around 10 km per century.

A number of specialists maintained support for such explanations into the 21st century,[32][33] and variations on this theme continued to feature in standard histories of English.

[34][35][36][37] Peter Schrijver said in 2014 that "to a large extent, it is linguistics that is responsible for thinking in terms of drastic scenarios" about demographic change in late Roman Britain.

[53][54] Critics of that model point out that in most cases, minority elite classes have not been able to impose their languages on a settled population.

[55][33][56] Furthermore, the archaeological and genetic evidence has cast doubt upon theories of expulsion and ethnic cleansing but also has tended not to support the idea that the extensive change seen in the post-Roman period was simply the result of acculturation by a ruling class.

In fact, many of the initial migrants seem to have been families, rather than warriors, with significant numbers of women taking part and elites not emerging until the sixth century.

[57][58][59][60] In light of that, the emerging consensus among historians, archaeologists and linguists is that the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain was not a single event and thus cannot be explained by any one particular model.

[60][66] In that view, therefore, the decline of Brittonic and British Latin in England can be explained by a combination of migration, displacement and acculturation in different contexts and areas.

[72] Richard Coates has disputed this assertion by arguing that while a satisfactory Celtic derivation for the tribal name has not been reached, it is "clearly not Germanic.

"[73] * regional, northern England; ** regional, southwestern England Supporters of the acculturation model in particular must account for the fact that in the case of a fairly swift language shift, involving second-language acquisition by adults, the learners' imperfect acquisition of the grammar and the pronunciation of the new language will affect it in some way.

Thus, one synthesis concluded that 'the evidence for Celtic influence on Old English is somewhat sparse, which only means that it remains elusive, not that it did not exist'.

[77] Although there is little consensus about the findings, extensive efforts have been made during the 21st century to identify substrate influence of Brittonic on English.

[78][79][80][81] Celtic influence on English has been suggested in several forms: However, various counter-arguments have been proposed: Coates has concluded that the strongest candidates for potential substrate features can be seen in regional dialects in the north and the west of England (roughly corresponding to Area 3 in Jackson's chronology), such as the Northern Subject Rule.