Chemical reactor

Chemical engineers design reactors to maximize net present value for the given reaction.

A batch reactor does not reach a steady state, and control of temperature, pressure and volume is often necessary.

The CISTR model is often used to simplify engineering calculations and can be used to describe research reactors.

In practice it can only be approached, particularly in industrial size reactors in which the mixing time may be very large.

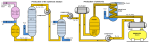

The reaction mixture is circulated in a loop of tube, surrounded by a jacket for cooling or heating, and there is a continuous flow of starting material in and product out.

In a PFR, sometimes called continuous tubular reactor (CTR),[10] one or more fluid reagents are pumped through a pipe or tube.

In some cases, very large reactors would be necessary to approach equilibrium, and chemical engineers may choose to separate the partially reacted mixture and recycle the leftover reactants.

A fermenter, for example, is loaded with a batch of medium and microbes which constantly produces carbon dioxide that must be removed continuously.

To overcome this problem, a continuous feed of gas can be bubbled through a batch of a liquid.

In general, in semibatch operation, one chemical reactant is loaded into the reactor and a second chemical is added slowly (for instance, to prevent side reactions), or a product which results from a phase change is continuously removed, for example a gas formed by the reaction, a solid that precipitates out, or a hydrophobic product that forms in an aqueous solution.

The rate of a catalytic reaction is proportional to the amount of catalyst the reagents contact, as well as the concentration of the reactants.

However, most petrochemical reactors are catalytic, and are responsible for most industrial chemical production, with extremely high-volume examples including sulfuric acid, ammonia, reformate/BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene), and fluid catalytic cracking.