Froissart's Chronicles

The Chronicles open with the events leading up to the deposition of Edward II in 1327, and cover the period up to 1400, recounting events in western Europe, mainly in England, France, Scotland, the Low Countries and the Iberian Peninsula, although at times also mentioning other countries and regions such as Italy, Germany, Ireland, the Balkans, Cyprus, Turkey and North Africa.

Froissart's work is perceived as being of vital importance to informed understandings of the European 14th century, particularly of the Hundred Years' War.

But modern historians also recognize that the Chronicles have many shortcomings as a historical source: they contain erroneous dates, have misplaced geography, give inaccurate estimations of sizes of armies and casualties of war, and may be biased in favour of the author's patrons.

For the earlier periods Froissart based his work on other existing chronicles, but his own experiences, combined with those of interviewed witnesses, supply much of the detail of the later books.

He was present at other significant events such as the baptism of Richard II in Bordeaux in 1367, the coronation of King Charles VI of France in Rheims in 1380, the marriage of Duke John of Berry and Jeanne of Boulogne in Riom and the joyous entry of the French queen Isabeau of Bavaria in Paris, both in 1389.

[1] It is true that Froissart often omits to talk about the common people, but that is largely the consequence of his stated aim to write not a general chronicle but a history of the chivalric exploits that took place during the wars between France and England.

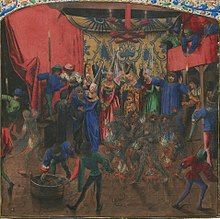

His Book II focuses extensively on popular revolts in different parts of western Europe (France, England and Flanders) and in this part of the Chronicles the author often demonstrates good understanding of the factors that influenced local economies and their effect on society at large; he also seems to have a lot of sympathy in particular for the plight of the poorer strata of the urban populations of Flanders.

He seems to have come from what we would today call a middle-class background, but spent much of his adult life in courts, and took on the world-view of the late medieval feudal aristocracy, who initially represented his readership.

In particular he denounced his earlier rhyming chronicle, whose accuracy, he admitted, had not always been as good as such important matters as war and knightly prowess require.

In order to improve the quality and historical accuracy of his work, Froissart declared his intention to follow now as his main source the Vrayes Chroniques of Jean Le Bel, who had expressed fierce criticism on verse as a suitable vehicle for serious history writing.

Le Bel had written his chronicle for Jean, lord of Beaumont, uncle of Philippa of Hainault, who had been a supporter of Queen Isabella and the rebellion which led to the deposition of Edward II in 1326.

Jean Le Bel himself, throughout his work expressed great admiration for Edward III, in whose 1327 Weardale campaign against the Scots he had fought.

Froissart seems to have written several new drafts or versions of Book I, which covers the period up to 1378/1379, at different points in time.

Book II, however, includes an extended account of the Flemish revolt against the count in the years 1379–1385, which Froissart had earlier composed as a separate text and which is known as his Chronicle of Flanders.

Most manuscripts of Book II contain one of the two earlier versions, which have an almost identical text, except for a small number of chapters in which there are substantial differences.

[22] It is codicologically connected to the 'Rome' manuscript of Book I, and it may have formed part of a final revision of the whole Chronicles which Froissart would have undertaken towards the end of his life.

A first version of Book III, which covers the years 1385 to 1390, but which also includes extensive flashback to the earlier periods, was possibly completed in 1390 or 1391 and is the one found in nearly all the surviving manuscripts.

There was something of a revival in interest from about 1470 in the Burgundian Low Countries, and some of the most extensive cycles of Flemish illumination were produced to illustrate Froissart's Chronicles.