Maximum parsimony (phylogenetics)

Of course, any phylogenetic algorithm could also be statistically inconsistent if the model it employs to estimate the preferred tree does not accurately match the way that evolution occurred in that clade.

Alternatively, phylogenetic parsimony can be characterized as favoring the trees that maximize explanatory power by minimizing the number of observed similarities that cannot be explained by inheritance and common descent.

Ideally, we would expect the distribution of whatever evolutionary characters (such as phenotypic traits or alleles) to directly follow the branching pattern of evolution.

Some authorities order characters when there is a clear logical, ontogenetic, or evolutionary transition among the states (for example, "legs: short; medium; long").

In some cases, repeated analyses are run, with characters reweighted in inverse proportion to the degree of homoplasy discovered in the previous analysis (termed successive weighting); this is another technique that might be considered circular reasoning.

Empirical, theoretical, and simulation studies have led to a number of dramatic demonstrations of the importance of adequate taxon sampling.

The most disturbing weakness of parsimony analysis, that of long-branch attraction (see below) is particularly pronounced with poor taxon sampling, especially in the four-taxon case.

As taxa are added, they often break up long branches (especially in the case of fossils), effectively improving the estimation of character state changes along them.

Because of the richness of information added by taxon sampling, it is even possible to produce highly accurate estimates of phylogenies with hundreds of taxa using only a few thousand characters.

Because of advances in computer performance, and the reduced cost and increased automation of molecular sequencing, sample sizes overall are on the rise, and studies addressing the relationships of hundreds of taxa (or other terminal entities, such as genes) are becoming common.

Although these taxa may generate more most-parsimonious trees (see below), methods such as agreement subtrees and reduced consensus can still extract information on the relationships of interest.

Trees are scored (evaluated) by using a simple algorithm to determine how many "steps" (evolutionary transitions) are required to explain the distribution of each character.

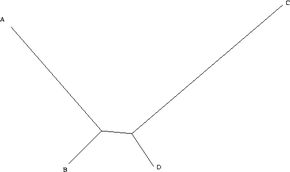

The trees resulting from parsimony search are unrooted: They show all the possible relationships of the included taxa, but they lack any statement on relative times of divergence.

Today's general consensus is that having multiple MPTs is a valid analytical result; it simply indicates that there is insufficient data to resolve the tree completely.

Even if multiple MPTs are returned, parsimony analysis still basically produces a point-estimate, lacking confidence intervals of any sort.

However, the direction of bias cannot be ascertained in individual cases, so assuming that high values bootstrap support indicate even higher confidence is unwarranted.

Branch support values are often fairly low for modestly-sized data sets (one or two steps being typical), but they often appear to be proportional to bootstrap percentages.

[18] However, interpretation of decay values is not straightforward, and they seem to be preferred by authors with philosophical objections to the bootstrap (although many morphological systematists, especially paleontologists, report both).

Thus, unless we are able to devise a model that is guaranteed to accurately recover the "true tree," any other optimality criterion or weighting scheme could also, in principle, be statistically inconsistent.

Another complication with maximum parsimony, and other optimality-criterion based phylogenetic methods, is that finding the shortest tree is an NP-hard problem.

[20] The only currently available, efficient way of obtaining a solution, given an arbitrarily large set of taxa, is by using heuristic methods which do not guarantee that the shortest tree will be recovered.

It has been asserted that a major problem, especially for paleontology, is that maximum parsimony assumes that the only way two species can share the same nucleotide at the same position is if they are genetically related.

However, it has been shown through simulation studies, testing with known in vitro viral phylogenies, and congruence with other methods, that the accuracy of parsimony is in most cases not compromised by this.

In practice, the technique is robust: maximum parsimony exhibits minimal bias as a result of choosing the tree with the fewest changes.

Parsimony is often characterized as implicitly adopting the position that evolutionary change is rare, or that homoplasy (convergence and reversal) is minimal in evolution.

Recent simulation studies suggest that parsimony may be less accurate than trees built using Bayesian approaches for morphological data,[21] potentially due to overprecision,[22] although this has been disputed.

There are a number of distance-matrix methods and optimality criteria, of which the minimum evolution criterion is most closely related to maximum parsimony.

From among the distance methods, there exists a phylogenetic estimation criterion, known as Minimum Evolution (ME), that shares with maximum-parsimony the aspect of searching for the phylogeny that has the shortest total sum of branch lengths.

[28][29] A subtle difference distinguishes the maximum-parsimony criterion from the ME criterion: while maximum-parsimony is based on an abductive heuristic, i.e., the plausibility of the simplest evolutionary hypothesis of taxa with respect to the more complex ones, the ME criterion is based on Kidd and Sgaramella-Zonta's conjectures (proven true 22 years later by Rzhetsky and Nei[30]) stating that if the evolutionary distances from taxa were unbiased estimates of the true evolutionary distances then the true phylogeny of taxa would have a length shorter than any other alternative phylogeny compatible with those distances.

Rzhetsky and Nei's results set the ME criterion free from the Occam's razor principle and confer it a solid theoretical and quantitative basis.