Classical Realism

The movement's aesthetic is classical in that it exhibits a preference for order, beauty, harmony and completeness; it is realist because its primary subject matter comes from the representation of nature based on the artist's observation.

Classical Realist painters have attempted to restore curricula of training that develop a sensitive, artistic eye and methods of representing nature that pre-date Modern Art.

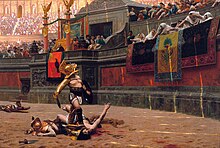

Their subject matter includes all of the traditional categories within Western Art: figurative, landscape, portraiture, indoor and outdoor genre and still life paintings.

[6] Classical Realist artists attempt to revive the idea of art production as it was traditionally understood: mastery of a craft in order to make objects that gratify and ennoble those who see them.

Like the 19th-century academic models from which it derives inspiration, the movement has drawn criticism for the premium placed upon technical performance, a tendency toward contrived and idealized depictions of the figure, and rhetorical overstatement when applied to epic narrative.

[9] These modern ateliers are founded with the goal of revitalizing art education by reintroducing rigorous training in traditional drawing and painting techniques, employing teaching methodologies that were used in the École des Beaux-Arts.

Under the atelier model, art students study in the studio of an established master to learn how to draw and paint with realistic accuracy and an emphasis on rendering form convincingly.

The foundation of these programs rests on an intensive study of the human figure, renderings of plaster casts of classical sculpture, and the emulation of their instructors.