Coordination polymer

A subclass of these are the metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, that are coordination networks with organic ligands containing potential voids.

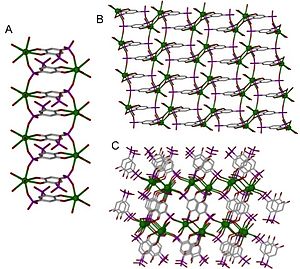

A structure can be determined to be one-, two- or three-dimensional, depending on the number of directions in space the array extends in.

The work of Alfred Werner and his contemporaries laid the groundwork for the study of coordination polymers.

Coordination polymers are often prepared by self-assembly, involving crystallization of a metal salt with a ligand.

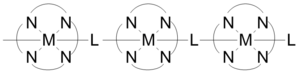

Metal centers, often called nodes or hubs, bond to a specific number of linkers at well defined angles.

Partially filled d orbitals, either in the atom or ion, can hybridize differently depending on environment.

This electronic structure causes some of them to exhibit multiple coordination geometries, particularly copper and gold ions which as neutral atoms have full d-orbitals in their outer shells.

In order to stabilize the structure and prevent collapse, the pores or channels are often occupied by guest molecules.

Most often, the guest molecule will be the solvent that the coordination polymer was crystallized in, but can really be anything (other salts present, atmospheric gases such as oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, etc.)

The presence of the guest molecule can sometimes influence the structure by supporting a pore or channel, where otherwise none would exist.

Some early commercialized coordination polymers are the Hofmann compounds, which have the formula Ni(CN)4Ni(NH3)2.

These materials crystallize with small aromatic guests (benzene, certain xylenes), and this selectivity has been exploited commercially for the separation of these hydrocarbons.

Flexible porous coordination polymers are potentially attractive for molecular storage, since their pore sizes can be altered by physical changes.

Luminescent coordination polymers typically feature organic chromophoric ligands, which absorb light and then pass the excitation energy to the metal ion.

[21][22] Coordination polymers can have short inorganic and conjugated organic bridges in their structures, which provide pathways for electrical conduction.

The conductivity is due to the interaction between the metal d-orbital and the pi* level of the bridging ligand.

Three-dimensional structures consisting of sheets of silver-containing polymers demonstrate semi-conductivity when the metal centers are aligned, and conduction decreases as the silver atoms go from parallel to perpendicular.

This originally orange solution turns either purple or green with the replacement of water with tetrahydrofuran, and blue upon the addition of diethyl ether.