Costumbrismo

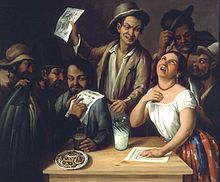

Costumbrismo (in Catalan: costumisme; sometimes anglicized as costumbrism, with the adjectival form costumbrist) is the literary or pictorial interpretation of local everyday life, mannerisms, and customs, primarily in the Hispanic scene, and particularly in the 19th century.

Juan López Morillas summed up the appeal of costumbrismo for writing about Latin American society as follows: the costumbristas' "preoccupation with minute detail, local color, the picturesque, and their concern with matters of style is frequently no more than a subterfuge.

Astonished by the contradictions observed around them, incapable of clearly understanding the tumult of the modern world, these writers sought refuge in the particular, the trivial or the ephemeral.

In the 19th century costumbrismo bursts out as a clear genre in its own right, addressing a broad audience: stories and illustrations often made their first or most important appearance in cheap periodicals for the general public.

Estébanez Calderón (who originally wrote for the abovementioned Correo Literario y Mercantil) looked for a "genuine" and picturesque Spain in the recent past of particular regions; Mesonero Romanos was a careful observer of the Madrid of his time, especially of the middle classes; Larra, according to José Ramón Lomba Pedraja, arguably transcended his genre, using the form of costumbrismo for political and psychological ideas.

Antonio María Segovia (1808–74), who mainly wrote pseudonymously as "El Estudiante"[4] and who founded the satiric-literary magazine El Cócora;[6] his collaborator Santos López Pelegrín (1801–46), "Abenámar"; many early contributors to Madrid's Semanario Pintoresco Español (1836-57[7]), Spain's first illustrated magazine; and such lesser lights as Antonio Neira de Mosquera (1818–53), "El Doctor Malatesta" (Las ferias de Madrid, 1845); Clemente Díaz, with whom costumbrismo took a turn toward the rural; Vicente de la Fuente (1817–89), portraying the lives of bookish students (in between writing serious histories); José Giménez Serrano, portraying a romantic Andalusia; Enrique Gil y Carrasco,[4] a Carlist[8] from Villafranca del Bierzo, friend of Alexander von Humboldt, and contributor to the Semanario Pintoresco Español;[9] and many other regionalists around Spain.

It combined essays by such "distinguished writers" (the volume's own choice of words) as William Makepeace Thackeray and Leigh Hunt with pictures of individuals emblematic of different English "types".

[4][10] A collective and hence, necessarily, uneven anthology of "types", Los españoles… was a mixture of verse and prose, and of writers and artists from various generations.

Illustrators included Leonardo Alenza (1807–45), Fernando Miranda y Casellas, Francisco Lameyer (1825–1877), Vicente Urrabieta y Ortiz, and Calixto Ortega.

In some ways, the omissions are as interesting as the inclusions: no direct representation of the aristocracy, of prominent businessmen, of the high clergy, or of the army, and except for the "popular" classes, the writing is a bit circumspect and cautious.

Flores turned to again to custumbrismo, of a sort, in 1853 with Ayer, hoy y mañana o la fe, el vapor y la electricidad (cuadros sociales de 1800, 1850 y 1899) ("Yesterday, today and tomorrow or faith, steam and electricity (social pictures of 1800, 1850, and 1899)") going Mesonero's "types lost" and "types found" one better by projecting a vision of the future influenced by the work of Émile Souvestre.

[4] Andrés Soria sees José María de Pereda (1833–1906) as the most successful fusion of costumbrista scenes into proper novels, especially his portrayals of La Montaña, the mountainous regions of Cantabria.

His Escenas montañesas (1864) is particularly in the costumbrista mode, with its mixture of urban, rural and seafaring scenes, and sections offering sketches of various milieus.

The magazine España, founded 1915, wrote about some new "types": the indolent golfo; the lower class señorito chulo with his airs and exaggerated fashions; the albañil or construction worker, but with far less sympathy than costumbristas in the previous century had portrayed their predecessors.

[4] A strong current of costumbrismo continued in 20th-century Madrid, including in poetry (Antonio Casero, 1874–1936) and theatre (José López Silva, 1860–1925; Carlos Arniches Barreda, 1866–1943).

[20] Typical subject matter included majos (lower class dandies) and their female equivalents, horsemen, bandits and smugglers, street urchins and beggars, Gypsies, traditional architecture, fiestas, and religious processions such as Holy Week in Seville.

Esteban Echeverría (1805–51) was a politically passionate Romantic writer whose work has strong costumbrista aspects; his El Matadero ("The Slaughterhouse") is still widely read.

Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810–84) and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1811–1888) both wrote at times in the genre, as did José Antonio Wilde (1813–83), in Buenos Aires desde setenta años atrás ("Buenos Aires from seventy years ago"); Vicente G. Quesada (1830–1913), in Recuerdos de un viejo ("Memories of an old man"); Lucio V. López (1848–94), in the novela La gran aldea ("The big village"); Martín Coronado (1850–1919), playwright; Martiniano Leguizamón (1858–1935), in the novel Montaraz; José S. Alvarez (1858–1903, "Fray Mocho"), in the story "Viaje al país de los matreros" ("A trip to bandit country"); Emma de la Barra (1861–1947), who wrote under the pseudonym César Duayen, in Stella; Joaquín V. González (1863–1923), in Mis montañas ("My Mountains"); Julio Sánchez Gardel (1879–1937), in numerous comedies; and Manuel Gálvez (1882–1962), in such novels as La maestra normal ("The normal school teacher") and La sombra del convento ("The sleep of the convent").

Other Central American costumbristas are José María Peralta Lagos (1875–1944, El Salvador), Ramón Rosa (1848–93, Honduras), Carlos Alberto Uclés (1854–1942, Honduras), and a distinguished line of Costa Rican writers: Manuel de Jesús Jiménez (1854–1916), Manuel González Zeledón (1864–1936), the verse writer Aquileo Echeverría (1866–1909), and, in the 20th century, Joaquín García Monge (1881–1958).

[28] Costumbrismo enters Chilean literature in some of the writing of José Zapiola (1804–85), Vicente Pérez Rosales (1807–86), Román Fritis (1829–74), Pedro Ruiz Aldea (ca.

Costumbrismo figures particularly heavily in stage comedies: El patio de los Tribunales ("The courtyard of the tribunals [of justice]", by Valentín Murillo (1841–1896); Don Lucas Gómez, by Mateo Martínez Quevedo (1848–1923); Chincol en sartén ("A sparrow in the pan") and En la puerta del horno ("In the gate of horn"), by Antonio Espiñeira (1855–1907); La canción rota ("The broken song"), by Antonio Acevedo Hernández (1886–1962); Pueblecito ("Little town") by Armando Moock (1894–1942).

In prose, costumbrismo mixes eventually into realism, with Manuel J. Ortiz (1870–1945) and Joaquín Díaz García (1877–1921) as important realists with costumbrista aspects.

[29] Rodríguez's work begins as a chronicle of the conquest of New Granada, but as it approaches his own time it becomes more and more detailed and quotidian, and its second half is a series of narratives that, according to Stephen M. Hart, give "lip service" to conventional morality while taking "a keen delight in recounting the various skullduggeries of witches, rogues, murderers, whores, outlaws, priests and judges.

[28] Cuba's leading costumbristas were Gaspar Betancourt Cisneros (1803–66, known as "El Lugareño"), Cirilo Villaverde (1812–94), and José María de Cárdenas y Rodríguez (1812–82).

Blacks are more present in the costumbrista works of Cesar Nicolas Penson (1855–1901), but he is far more sympathetic to his white characters, portraying Haitians as fierce beasts.

In addition, José López Portillo y Rojas (1850–1923), Rafael Delgado (1853–1914), Ángel del Campo (1868–1908) and Emilio Rabasa (1856–1930) can be seen as costumbristas, but their work can also be considered realist.

[28] Peruvian costumbrismo begins with José Joaquín de Larriva y Ruiz (1780–1832), poeta and journalist and his younger, irreverent, Madrid-educated collaborator Felipe Pardo y Aliaga (1806–68).

[28][35] Other Peruvian costumbristas are satirist and verse writer Pedro Paz Soldán y Unanue (1839–1895), Abelardo M. Gamarra (1850–1924), and the nostalgic José Gálvez (1885–1957).

Manuel Fernández Juncos (1846–1928), born in Asturias, Spain, emigrated at age eleven to the island and wrote Tipos y caracteres y Costumbres y tradiciones ("Types and characters and customs and traditions").

[28][36] Prominent Uruguayan costumbristas include Santiago Maciel (1862–1931), Manuel Bernárdez (1867–1942), Javier de Viana (1868–1926), Adolfo Montiel Ballesteros (1888–1971), and Fernán Silva Valdés (1887–1975).