Counter-Maniera

Hall, a leading art historian of the period and mentee of Freedberg, was criticised by a reviewer of her After Raphael: Painting in Central Italy in the Sixteenth Century for her "fundamental flaw" in continuing to use this and other terms, despite an apologetic "Note on style labels" at the beginning of the book and a promise to keep their use to a minimum.

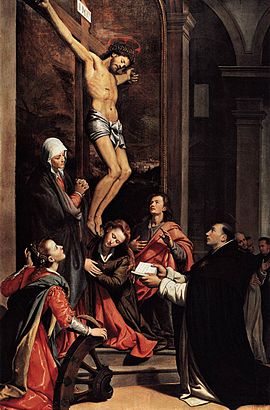

[7] The term is most often applied to painters in Florence and Rome who reacted against the prevailing style in these centres of full-blooded maniera, without a fundamental rejection of its underlying principles.

Elements of the maniera that are removed include the impulse to push to the extreme, the willingness to sacrifice everything for a graceful effect, playfulness and wit, and the readiness to let the details and ambience of a painting crowd out or submerge the supposed main figures, that must be hunted out by the learned viewer.

[9] In its latest phase, from about 1585, the need for popular appeal appears to have been recognized by artists and commissioners in the church, leading to some relaxation of the austerity of earlier periods, and sometimes to sentimentality.

For Freedberg this was "a new and un-Maniera attitude to art";[11] elsewhere he cautions against confusing Counter-Maniera with "anti-Maniera", apparently reflecting "Anti-Mannerism", the term used by Walter Friedländer for the "palpable break in the stylistic development of Italian painting" that occurred "sometime around 1590".

Freedberg says frankly: "Boredom is a requisite of the Roman Counter-Maniera style, invading even the art of the few painters whose inspiration may be too considerable and too authentic to be sealed off wholly".