Croat–Bosniak War

On 23 February 1994, a lasting ceasefire was agreed, and an agreement ending the hostilities was signed in Washington on 18 March 1994, by which time the Croatian Defence Council had suffered significant territorial losses.

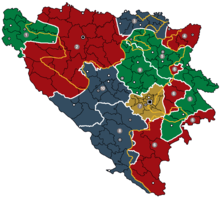

The agreement led to the establishment of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the resumption of joint operations against Serb forces, which helped alter the military balance and bring the Bosnian War to an end.

[24] A number of them joined the Croatian Defence Forces (HOS), a paramilitary wing of the far-right HSP, led by Blaž Kraljević,[22][52] which "supported Bosnian territorial integrity much more consistently and sincerely than the HVO".

[56] In February 1992, in the first of several meetings, Josip Manolić, Tuđman's aide and previously the Croatian Prime Minister, met with Radovan Karadžić in Graz, Austria.

[62] In mid-June, the combined military efforts of the ARBiH and HVO managed to break the siege of Mostar[63] and capture the east bank of the Neretva River, that was under control of the VRS for two months.

[91] On 4 September 1992, Croatian officials in Zagreb confiscated a large amount of weapons and ammunition aboard an Iranian plane that was supposed to transport Red Crescent humanitarian aid for Bosnia.

[92] On 7 September, HVO demanded that the Bosniak militiamen withdraw from Croatian suburbs of Stup, Bare, Azići, Otes, Dogladi and parts of Nedzarici in Sarajevo and issued an ultimatum.

[64] In the latter half of 1992, foreign Mujahideen hailing mainly from North Africa and the Middle East began to arrive in central Bosnia and set up camps for combatant training with the intent of helping their "Muslim brothers" against the Serbs.

Initially they were organized in the Territorial Defence (TO), which had been a separate part of the armed forces of Yugoslavia, and in various paramilitary groups such as the Patriotic League, Green Berets and Black Swans.

[21] The Zagreb government deployed HV units and Ministry of the Interior (MUP RH) special forces into Posavina and Herzegovina in 1992 to conduct operations against the Serbs together with the HVO.

Albanian, Dutch, American, Irish, Polish, Australian, New Zealand, French, Swedish, German, Hungarian, Norwegian, Canadian and Finnish volunteers were organized into the Croatian 103rd (International) Infantry Brigade.

Intense fighting continued in the Busovača area, where the HVO attacked the Kadića Strana part of the town, in which numerous Bosniak civilians were expelled or killed,[159] until a truce was signed on 30 January.

[177] EC representatives wanted to sort out the Croat-Bosniak tensions, but the collective Presidency fell apart, with the Croat side objecting that decisions of the government were made arbitrarily by Izetbegović and his close associates.

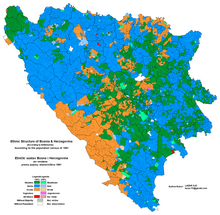

[182] Many thought that this plan contributed to the escalation of the Croat-Bosniak war, encouraging the struggle for territory between Croat and Bosniak forces in parts of central Bosnia that were ethnically mixed.

[200] The HVO overestimated their power and the ability of securing the Croat enclaves, while the ARBiH leaders thought that Bosniak survival depended on seizing territory in central Bosnia rather than in a direct confrontation with the stronger VRS around Sarajevo.

Although the armed confrontation in Herzegovina and central Bosnia strained the relationship between them, it did not result in violence and the Croat-Bosniak alliance held, particularly in places in which both were heavily outmatched by Serb forces.

[211][212] In other areas where the alliance collapsed, the VRS, still the strongest force, occasionally cooperated with both the HVO and ARBiH, pursuing a local balancing policy and allying with the weaker side.

The Sarajevo government used that time to reorganize its army, naming Rasim Delić as Commander of the ARBiH, and to prepare an offensive against the HVO in the Bila Valley, where the city of Travnik was located, and in the Kakanj municipality.

As the ARBiH approached the city, thousands of Croats began to flee, and the outnumbered HVO directed its forces to protect an escape route to Vareš, east of Kakanj.

The HV eventually assumed control of the entire confrontation line with the VRS in southern Herzegovina, north of Dubrovnik, which enabled the HVO to direct more of its troops against the ARBiH.

[281] By February 1994, the Secretary-General of the UN reported that between 3,000 and 5,000 Croatian regular troops were in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the UN Security Council condemned Croatia, warning that if it did not end "all forms of interference" there would be "serious measures" taken.

[283] On 26 February talks began in Washington, D.C., between the Bosnian government leaders and Mate Granić, Croatian Minister of Foreign Affairs, to discuss the possibilities of a permanent ceasefire and a confederation of Bosniak and Croat regions.

[295] Nonetheless, news stories were fabricated to incite hatred,[296] and state controlled television and radio pushed anti-Bosniak propaganda, escalating tensions between Bosniaks and Croats in Croatia.

[311] In May 1990, Tuđman said that Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina "form a geographic and political whole, and in the course of history they were generally in a single united state", but suggested that its citizens should "decide their own fate through a referendum".

"[324] On 29 November 2017, the ICTY Appeals Chamber issued its final judgment, reiterating and confirming the Trial Chanber's finding of a Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE) between the HZ H-B leaders and Franjo Tudjman,[325] The Appeals Chamber confirmed as correct the Trial Chamber's findings of specific elements of this JCE including: (1) that Tudjman intended to divide Bosnia and intervened in Bosnia with the aim of creating a Greater Croatia (2) that Tudjman controlled Herceg-Bosnia's military activities due to "a joint command structure”,(3) that Tudman pursued a "two-track policy", i.e. , publicly advocating respect for the existing BiH borders, while privately supporting the partition of BiH between Croats and Serbs.

[338] In February 1997, during the Kurban Bajram holiday, an incident occurred in Mostar between Croat policemen and a group of several hundred Bosniaks that were marching to Liska Street cemetery.

[339][340] In August 1997, Bosniak returnees to Jajce were attacked by mobs, involving HVO militia, upon the instigation of local political leaders, including Dario Kordić, former Vice-President of Herzeg-Bosnia.

[342] In 1996, the US put pressure on the Bosniak leadership to close its remaining ties with Islamist groups and remove Hasan Čengić, who was involved in Iranian arms shipments to the country, from his position of Deputy Minister of Defence.

[368] In December 2004, Dario Kordić, former Vice President of Herzeg-Bosnia, was sentenced to 25 years of prison for war crimes aimed at ethnically cleansing Bosniaks in the area of central Bosnia.

[376] Bosnian commander Sefer Halilović was charged with one count of violation of the laws and customs of war on the basis of superior criminal responsibility of the incidents during Operation Neretva '93 and found not guilty.