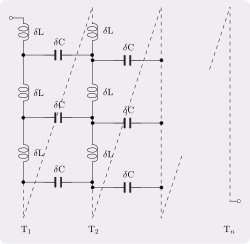

Distributed-element model

This is in contrast to the more common lumped-element model, which assumes that these values are lumped into electrical components that are joined by perfectly conducting wires.

The use of infinitesimals will often require the application of calculus, whereas circuits analysed by the lumped-element model can be solved with linear algebra.

The location of this point is dependent on the accuracy required in a specific application, but essentially, it needs to be used in circuits where the wavelengths of the signals have become comparable to the physical dimensions of the components.

An often-quoted engineering rule of thumb (not to be taken too literally because there are many exceptions) is that parts larger than one-tenth of a wavelength will usually need to be analysed as distributed elements.

Another example of the use of distributed elements is in the modelling of the base region of a bipolar junction transistor at high frequencies.

Amongst the fields that use this technique are geophysics (because it avoids having to dig into the substrate) and the semiconductor industry (for the similar reason that it is non-intrusive) for testing bulk silicon wafers.

Unlike the transmission line example, the need to apply the distributed-element model arises from the geometry of the setup, and not from any wave propagation considerations.

The most common approach is to roll up all the distributed capacitance into one lumped element in parallel with the inductance and resistance of the coil.