The eclipse of Darwinism

[12] By the end of the 19th century, criticism of natural selection had reached the point that in 1903 the German botanist, Eberhard Dennert [de], edited a series of articles intended to show that "Darwinism will soon be a thing of the past, a matter of history; that we even now stand at its death-bed, while its friends are solicitous only to secure for it a decent burial.

"[14] He added, however, that there were problems preventing the widespread acceptance of any of the alternatives, as large mutations seemed too uncommon, and there was no experimental evidence of mechanisms that could support either Lamarckism or orthogenesis.

[15] Ernst Mayr wrote that a survey of evolutionary literature and biology textbooks showed that as late as 1930 the belief that natural selection was the most important factor in evolution was a minority viewpoint, with only a few population geneticists being strict selectionists.

Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it was immoral, and left little room for teleology or the concept of progress in the development of life.

[10] Another factor was the rise of a new faction of biologists at the end of the 19th century, typified by the geneticists Hugo DeVries and Thomas Hunt Morgan, who wanted to recast biology as an experimental laboratory science.

They distrusted the work of naturalists like Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, dependent on field observations of variation, adaptation, and biogeography, considering these overly anecdotal.

[19] British science developed in the early 19th century on a basis of natural theology which saw the adaptation of fixed species as evidence that they had been specially created to a purposeful divine design.

Similarly, Louis Agassiz saw Ernest Haeckel's recapitulation theory, which held that the embryological development of an organism repeats its evolutionary history, as symbolising a pattern of the sequence of creations in which humanity was the goal of a divine plan.

Its anonymous author Robert Chambers proposed a "law" of divinely ordered progressive development, with transmutation of species as an extension of recapitulation theory.

Two years later, in his review of On the Origin of Species, Owen attacked Darwin while at the same time openly supporting evolution,[21] expressing belief in a pattern of transmutation by law-like means.

This idealist argument from design was taken up by other naturalists such as George Jackson Mivart, and the Duke of Argyll who rejected natural selection altogether in favor of laws of development that guided evolution down preordained paths.

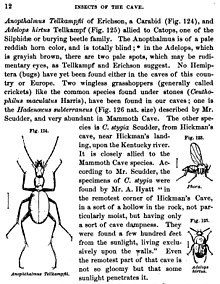

[28][29] Packard argued that the loss of vision in the blind cave insects he studied was best explained through a Lamarckian process of atrophy through disuse combined with inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Agassiz never accepted evolution; his followers did, but they continued his program of searching for orderly patterns in nature, which they considered to be consistent with divine providence, and preferred evolutionary mechanisms like neo-Lamarckism and orthogenesis that would be likely to produce them.

[29][34] As a consequence of the debate over the viability of neo-Lamarckism, in 1896 James Mark Baldwin, Henry Fairfield Osborne and C. Lloyd Morgan all independently proposed a mechanism where new learned behaviors could cause the evolution of new instincts and physical traits through natural selection without resort to the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

[36] Orthogenesis had a significant following in the 19th century, its proponents including the Russian biologist Leo S. Berg, and the American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn.

De Vries looked for evidence of mutation extensive enough to produce a new species in a single generation and thought he found it with his work breeding the evening primrose of the genus Oenothera, which he started in 1886.

De Vries's ideas were influential in the first two decades of the 20th century, as some biologists felt that mutation theory could explain the sudden emergence of new forms in the fossil record; research on Oenothera spread across the world.

[40] Morgan was a supporter of de Vries's mutation theory and was hoping to gather evidence in favor of it when he started working with the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster in his lab in 1907.

However, it was a researcher in that lab, Hermann Joseph Muller, who determined in 1918 that the new varieties de Vries had observed while breeding Oenothera were the result of polyploid hybrids rather than rapid genetic mutation.

Their work recognized that the vast majority of mutations produced small effects that served to increase the genetic variability of a population rather than creating new species in a single step as the mutationists assumed.

However, historians of science such as Mark Largent have argued that while biologists broadly accepted the extensive evidence for evolution presented in The Origin of Species, there was less enthusiasm for natural selection as a mechanism.