Economic history of China before 1912

The relative economic status of Europe and China during most of the Qing (1644–1912 AD/CE) remains a matter of debate,[n 1] but a Great Divergence was apparent in the 19th century,[7] pushed by the Industrial and Technological Revolutions.

[22] Although the highly stratified[23] Erlitou society has left no writing, some historians have identified it as the legendary Xia dynasty mentioned in traditional Chinese accounts as preceding the Shang.

[41] The 4th-century Mencius claims that the early Zhou developed the well-field system,[n 3] a pattern of land occupation in which eight peasant families cultivated fields around a central plot that they farmed for a lord.

[72] In the early Western Han, the wealthiest men in the empire were merchants who produced and distributed salt and iron[73] and gained wealth that rivalled the annual tax revenues collected by the imperial court.

[73] This policy was in line with Emperor Wu's expansionary goals of challenging the nomadic Xiongnu Confederation while colonising the Hexi Corridor and what is now Xinjiang of Central Asia, Northern Vietnam, Yunnan, and North Korea.

[81] Sources of revenue used to fund Emperor Wu's military campaigns and colonisation efforts included seizures of lands from nobles, the sale of offices and titles, increased commercial taxes, and the issuing of government minting of coins.

After the defeat of the Xiongnu, however, Chinese armies established themselves in Central Asia and the Western Regions, starting the famed Silk Road, which became a major avenue of international trade.

[95] Jin rulers granted large tracts of land in the south to Chinese immigrants and landowners fleeing barbarian rule, who preserved the system of government that was in place before the uprising.

[96] The economic prosperity of southern China continued after Liu Song's fall and was greatest during the succeeding Liang dynasty, which briefly reconquered the North with 7,000 troops under the command of general Chen Qingzhi.

Emperor Xuanzong's reign ended with the Arab victory at Talas and the An Shi Rebellion, the first war inside China in over 120 years, led by a Sogdian general named An Lushan who used a large number of foreign troops.

During their rule, the Shatuo gave the vital Sixteen Prefectures area, containing the natural geographical defences of North China and the eastern section of the Great Wall, to the Khitan, another barbarian people.

For their organisational skills, Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais state that Song dynasty merchants: ... set up partnerships and joint stock companies, with a separation of owners (shareholders) and managers.

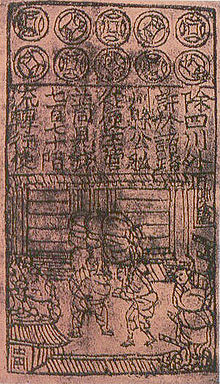

Although businesses began to issue private bills of exchange, by the mid-11th century the central government introduced its paper money, produced using woodblock printing and backed by bronze coins.

These reforms included nationalising industries such as tea, salt and liquor, and adopting a policy of directly transporting goods in abundance in one region to another, which Wang believed would eliminate the need for merchants.

These policies were extremely controversial, especially to Orthodox Confucians who favoured laissez faire, and were largely repealed after Wang Anshi's death, except during the reign of Emperor Huizong.

[179] In addition, the Mongol government later imposed high taxes and extensively nationalised major sectors of the economy, greatly damaging what was left of China's economic development.

By 1360, much of South China was free of Mongol rule and had been divided into regional states, such as Zhu Yuanzhang's Ming, Zhang Shichen's Wu and Chen Yolian's Han.

[211] Legal trade was restricted to tribute delegations sent to or by official representatives of foreign governments,[212] although this took on an epic scale under the Yongle Emperor with Zheng He's treasure voyages to Southeast Asia, India, and eastern Africa.

The size of the late Ming economy is a matter of conjecture, with Twitchett claiming it to be the largest and wealthiest nation on earth[200] and Maddison estimating its per capita GDP as average within Asia and lower than Europe's.

In the matter of commodity production and circulation, the Ming marked a turning point in Chinese history, both in the scale at which goods were being produced for the market, and in the nature of the economic relations that governed commercial exchange.

In fact, like the Ming before it, the Qing Empire was dependent on foreign trade for the Japanese and South American silver that underpinned its monetary system, and the ban was not effective until a more severe order followed in 1661[254] upon the ascension of the Kangxi Emperor.

[264] In addition to their blossoming power within their metropolitan cores, these merchants also utilized their wealth to gain social status within the Qing hierarchy by purchasing license as scholars, thus elevating themselves within the Confucian hierarchical system.

British officials noted the unrestrained influx of new smugglers was greatly alarming the Chinese but were unable to rein them in before the viceroy Lin Zexu placed the foreign factories under complete blockade, demanding the surrender of all opium held in the Pearl River Delta.

[268] Anger at Qing concessions and surprise at their weakness was already prompting rebellions before disastrous flooding in the early 1850s – inter alia, shifting the mouth of the Yellow River from south of the Shandong peninsula to north of it – ruined and dislocated millions.

The maintenance of army garrisons to maintain order in Xinjiang and its adjunct administration cost tens of thousands of taels of silver annually, which required subsidies from agricultural taxes levied in the wealthier provinces.

The attendant era of warlords and civil war accelerated the decline of the Chinese economy, whose percentage of the world gross domestic product rapidly fell,[275] although at the time Europe and United States also went through Industrial and Technological Revolution that jumped up their share.

[8] After defeating China in two wars, Great Britain secured treaties that created special rights for it and for other imperialist powers including France and Germany, as well as the United States and Japan.

China's communications with the outside world were dramatically transformed in 1871 when the Great Northern telegraphic company opened cables linking Shanghai to Hong Kong, Singapore, Nagasaki, and Vladivostok, with connections to India and Europe.

[283] The European community promoted technological and economic innovation, as well as knowledge industries, that proved especially attractive to Chinese entrepreneurs as models for their own cities across the growing nation.

Chinese merchants headquartered there set up branches across the Southeast Asia, including British Singapore and Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, French Indochina and the American Philippines.