Electromagnet

Electromagnets are widely used as components of other electrical devices, such as motors, generators, electromechanical solenoids, relays, loudspeakers, hard disks, MRI machines, scientific instruments, and magnetic separation equipment.

[2] Danish scientist Hans Christian Ørsted discovered in 1820 that electric currents create magnetic fields.

In the same year, the French scientist André-Marie Ampère showed that iron can be magnetized by inserting it into an electrically fed solenoid.

However, Sturgeon's magnets were weak because the uninsulated wire he used could only be wrapped in a single spaced-out layer around the core, limiting the number of turns.

The magnetic domain theory of how ferromagnetic cores work was first proposed in 1906 by French physicist Pierre-Ernest Weiss, and the detailed modern quantum mechanical theory of ferromagnetism was worked out in the 1920s by Werner Heisenberg, Lev Landau, Felix Bloch, and others.

[9] For example, a 12-inch-long coil (ℓ = 12 in) with a long plunger with a cross section of one inch square (A = 1 in2) and 11,200 ampere-turns (N I = 11,200 Aturn) had a maximum pull of 8.75 pounds (corresponding to C = 0.0094 psi).

The larger the current passed through the wire coil, the more the domains align, and the stronger the magnetic field is.

Once all the domains are aligned, any additional current only causes a slight increase in the strength of the magnetic field.

[2] For most high-permeability core steels, the maximum possible strength of the magnetic field is around 1.6 to 2 teslas (T).

When the current in the coil is turned off, most of the domains in the core material lose alignment and return to a random state, and the electromagnetic field disappears.

A related equation is the Biot–Savart law, which gives the magnetic field due to each small segment of current.

Likewise, on the solenoid, the force exerted by an electromagnet on a conductor located at a section of core material is: This equation can be derived from the energy stored in a magnetic field.

However, computing the magnetic field and force exerted by ferromagnetic materials in general is difficult for two reasons.

For precise calculations, computer programs that can produce a model of the magnetic field using the finite element method are employed.

Since most of the magnetic field is confined within the outlines of the core loop, this allows a simplification of the mathematical analysis.

For an electromagnet with a single magnetic circuit, Ampere's Law reduces to:[2][20][21] This is a nonlinear equation, because the permeability of the core

For a closed magnetic circuit (no air gap), most core materials saturate at a magnetomotive force of roughly 800 ampere-turns per meter of flux path.

Given an air gap of 1mm, a magnetomotive force of about 796 ampere-turns is required to produce a magnetic field of 1 T. For a closed magnetic circuit (no air gap), such as would be found in an electromagnet lifting a piece of iron bridged across its poles, equation (Eq.

To determine the force between two electromagnets (or permanent magnets) in these cases, a special analogy called a magnetic-charge model can be used.

This model assumes point-like poles (instead of surfaces), and thus it only yields a good approximation when the distance between the magnets is much larger than their diameter; thus, it is useful just for determining a force between them.

The only power consumed in a direct current (DC) electromagnet under steady-state conditions is due to the resistance of the windings, and is dissipated as heat.

Some large electromagnets require water cooling systems in the windings to carry off the waste heat.

More often, a diode is used to prevent voltage spikes by providing a path for the current to recirculate through the winding until the energy is dissipated as heat.

To prevent them, the cores of AC electromagnets are made of stacks of thin steel sheets, or laminations, oriented parallel to the magnetic field, with an insulating coating on the surface.

Any remaining eddy currents must flow within the cross-section of each individual lamination, which reduces losses greatly.

Instead of using ferromagnetic materials, these use superconducting windings cooled with liquid helium, which conduct current without electrical resistance.

However, in high-power applications this can be offset by lower operating costs, since after startup no power is required for the windings, since no energy is lost to ohmic heating.

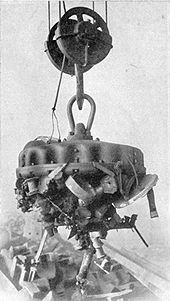

[24] Instead of wire windings, a Bitter magnet consists of a solenoid made of a stack of conducting disks, arranged so that the current moves in a helical path through them, with a hole through the center where the maximum field is created.

The disks are pierced with holes through which cooling water passes to carry away the heat caused by the high current.

While this method may seem very destructive, shaped charges redirect the blast outward to minimize harm to the experiment.

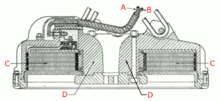

B – magnetic field in the core

B F – fringing fields; in the gaps G , the magnetic field lines bulge out, so the field strength is less than in the core: B F < B

B L – leakage flux ; magnetic field lines which do not follow complete magnetic circuit

L – average length of the magnetic circuit (used in Eq. 3 ). It is the sum of the length L core in the iron core pieces and the length L gap in the air gaps G .

Both the leakage flux and the fringing fields get larger as the gaps are increased, reducing the force exerted by the magnet.