Electrophoretic deposition

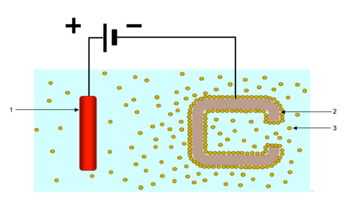

A characteristic feature of this process is that colloidal particles suspended in a liquid medium migrate under the influence of an electric field (electrophoresis) and are deposited onto an electrode.

Applications of non-aqueous EPD are currently being explored for use in the fabrication of electronic components and the production of ceramic coatings.

It has been widely used to coat automobile bodies and parts, tractors and heavy equipment, electrical switch gear, appliances, metal furniture, beverage containers, fasteners, and many other industrial products.

Thick films produced this way allow cheaper and more rapid synthesis relative to sol-gel thin-films, along with higher levels of photocatalyst surface area.

Furthermore, EPD has been used to produce customized microstructures, such as functional gradients and laminates, through suspension control during processing.

In the 1930s the first patents were issued which described base neutralized, water dispersible resins specifically designed for EPD.

The overall industrial process of electrophoretic deposition consists of several sub-processes: During the EPD process itself, direct current is applied to a solution of polymers with ionizable groups or a colloidal suspension of polymers with ionizable groups which may also incorporate solid materials such as pigments and fillers.

There are several mechanisms by which material can be deposited on the electrode: The primary electrochemical process which occurs during aqueous electrodeposition is the electrolysis of water.

Onium salts, which have been used in the cathodic process, are not protonated bases and do not deposit by the mechanism of charge destruction.

As the colloidal particles reach the solid object to be coated, they become squeezed together, and the water in the interstices is forced out.

As more and more charged groups are concentrated into a smaller volume, this increases the ionic strength of the medium, which also assists in precipitating the materials out of solution.

High throwpower electrophoretic paints typically use application voltages in excess of 300 volts DC.

The causes and mechanisms for rupturing are not completely understood, however, the following is known: There are two major categories of EPD chemistries: anodic and cathodic.

These types crosslinkers are relatively inexpensive and provide a wide range of cure and performance characteristics which allow the coating designer to tailor the product for the desired end use.

The aromatic polyurethane and urea type crosslinker is one of the significant reasons why many cathodic electrocoats show high levels of protection against corrosion.

However, coatings containing aromatic urethane crosslinkers generally do not perform well in terms of UV light resistance.

A significant undesired side reaction which occurs during the baking process produces aromatic polyamines.

Besides the two major categories of anodic and cathodic, EPD products can also be described by the base polymer chemistry which is utilized.

The description and the generally touted advantages are as follows: The rate of electrophoretic deposition (EPD) is dependent on multiple different kinetic processes acting in concert.

One of the primary kinetic processes involved in EPD is electrophoresis, the movement of charged particles in response to an electric field.

This section will discuss the conditions that determine the rates of each of these processes and how those variables are incorporated into different models used to evaluate EPD.

Without sufficient surface charge to balance the van der Waals attractive forces between particles, they will aggregate.

Particle size, zeta potential, and the solvent's conductivity, viscosity, and dielectric constant also determine the dispersion's stability.

[4] So long as the dispersion is stable, the initial rate of deposition will be primarily determined by the electric field strength.

Solution resistance can dissipate the applied voltage, so the actual surface charge on each electrode may be lower than intended.

The simple linear approximation applied by Hamaker's law degrades under higher voltages and longer deposition times.

Under higher voltage, chemical reactions, such as reduction, driven by the influence of the applied field can obscure the kinetics.

In determining the applicability of EPD to a system it is necessary to ensure the colloidal stability, and the combination of applied voltage and reaction time that will yield the intended deposited thickness.

In certain applications, such as the deposition of ceramic materials, voltages above 3–4V cannot be applied in aqueous EPD if it is necessary to avoid the electrolysis of water.

Ethanol, acetone, and methyl ethyl ketone are examples of solvents which have been reported as suitable candidates for use in electrophoretic deposition.