Ashoka

In the words of American academic John S. Strong, it is sometimes helpful to think of Ashoka's messages as propaganda by a politician whose aim is to present a favourable image of himself and his administration, rather than record historical facts.

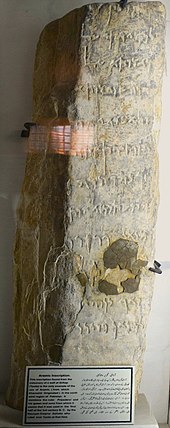

[13] An inscription discovered at Sirkap mentions a lost word beginning with "Priyadari", which is theorised to be Ashoka's title "Priyadarshi" since it has been written in Aramaic of 3rd century BCE, although this is not certain.

[18] The Buddhist legends about Ashoka exist in several languages, including Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, Chinese, Burmese, Khmer, Sinhala, Thai, Lao, and Khotanese.

[40] The Ashokavadana also names his father as Bindusara, but traces his ancestry to Buddha's contemporary king Bimbisara, through Ajatashatru, Udayin, Munda, Kakavarnin, Sahalin, Tulakuchi, Mahamandala, Prasenajit, and Nanda.

[41] The 16th century Tibetan monk Taranatha, whose account is a distorted version of the earlier traditions,[26] describes Ashoka as son of king Nemita of Champarana from the daughter of a merchant.

[55] Takshashila was a prosperous and geopolitically influential city, and historical evidence proves that by Ashoka's time, it was well-connected to the Mauryan capital Pataliputra by the Uttarapatha trade route.

[60] According to the Mahavamsa, Bindusara appointed Ashoka as the Viceroy of Avantirastra (present day Ujjain district),[53] which was an important administrative and commercial province in central India.

[88] However, unlike the north Indian tradition, the Sri Lankan texts do not mention any specific evil deeds performed by Ashoka, except his killing of 99 of his brothers.

Thence arises the remorse of His Sacred Majesty for having conquered the Kalingas because the conquest of a country previously unconquered involves the slaughter, death, and carrying away captive of the people.

[95] Some earlier writers believed that Ashoka dramatically converted to Buddhism after seeing the suffering caused by the war since his Major Rock Edict 13 states that he became closer to the dhamma after the annexation of Kalinga.

[102] The Dipavamsa states that Ashoka invited several non-Buddhist religious leaders to his palace and bestowed great gifts upon them in the hope that they would answer a question posed by the king.

[108] The Ashokavadana states that Ashoka collected seven out of the eight relics of Gautama Buddha, and had their portions kept in 84,000 boxes made of gold, silver, cat's eye, and crystal.

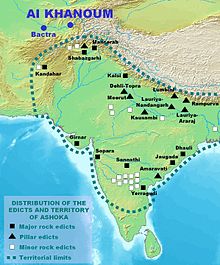

[19] Next, with Moggaliputta-Tissa's help, Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to distant regions such as Kashmir, Gandhara, Himalayas, the land of the Yonas (Greeks), Maharashtra, Suvannabhumi, and Sri Lanka.

[20] Ashoka's own inscriptions also appear to omit any mention of these events, recording only one of his activities during this period: in his 19th regnal year, he donated the Khalatika Cave to ascetics to provide them a shelter during the rainy season.

[129] However, epigraphic evidence suggests that the spread of Buddhism in north-western India and Deccan region was less because of Ashoka's missions, and more because of merchants, traders, landowners and the artisan guilds who supported Buddhist establishments.

[132] For several reasons, scholars say, these stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be clear fabrications arising out of sectarian propaganda.

[146] The Sri Lankan tradition uses the word samvasa to describe the relationship between Ashoka and Devi, which modern scholars variously interpret as sexual relations outside marriage, or co-habitation as a married couple.

[167] Ashoka's various inscriptions suggest that he devoted himself to the propagation of "Dharma" (Pali: Dhamma), a term that refers to the teachings of Gautama Buddha in the Buddhist circles.

[153] The inscriptions suggest that for Ashoka, Dharma meant "a moral polity of active social concern, religious tolerance, ecological awareness, the observance of common ethical precepts, and the renunciation of war.

"[168] For example: Modern scholars have variously understood this dhamma as a Buddhist lay ethic, a set of politico-moral ideas, a "sort of universal religion", or as an Ashokan innovation.

[11] Ashoka instituted a new category of officers called the dhamma-mahamattas, who were tasked with the welfare of the aged, the infirm, the women and children, and various religious sects.

[169] The writings of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrims such as Faxian and Xuanzang suggest that Ashoka's inscriptions mark the important sites associated with Gautama Buddha.

[176] Because he banned hunting, created many veterinary clinics and eliminated meat eating on many holidays, the Mauryan Empire under Ashoka has been described as "one of the very few instances in world history of a government treating its animals as citizens who are as deserving of its protection as the human residents".

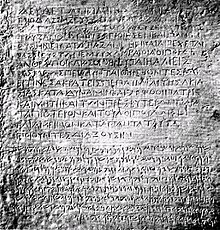

Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamktis, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dhamma.

The Chinese writer Pao Ch'eng's Shih chia ju lai ying hua lu asserts that an insignificant act like gifting dirt could not have been meritorious enough to cause Ashoka's future greatness.

Ashoka is often credited with the beginning of stone architecture in India, dedicated to Buddhism, possibly following the introduction of stone-building techniques by the Greeks after Alexander the Great.

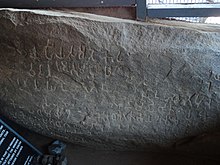

[206] Before Ashoka, the royal communications appear to have been written on perishable materials such as palm leaves, birch barks, cotton cloth, and possibly wooden boards.

Sir Alexander Cunningham, a British archaeologist and army engineer, and often known as the father of the Archaeological Survey of India, unveiled heritage sites like the Bharhut Stupa, Sarnath, Sanchi, and the Mahabodhi Temple.

Thapar writes about Ashoka that "We need to see him both as a statesman in the context of inheriting and sustaining an empire in a particular historical period, and as a person with a strong commitment to changing society through what might be called the propagation of social ethics.

For example, Amartya Sen writes, "The Indian Emperor Ashoka in the third century BCE presented many political inscriptions in favor of tolerance and individual freedom, both as a part of state policy and in the relation of different people to each other".