Age of Enlightenment

[1][2] The Enlightenment, which valued knowledge gained through rationalism and empiricism, was concerned with a range of social ideas and political ideals such as natural law, liberty, and progress, toleration and fraternity, constitutional government, and the formal separation of church and state.

[3][4][5] The Enlightenment was preceded by and overlapped the Scientific Revolution, which included the work of Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, Pierre Gassendi, Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton, among others, as well as the rationalist philosophy of Descartes, Hobbes, Spinoza, Leibniz, and John Locke.

[17][18] Some of figures of the Enlightenment included Cesare Beccaria, George Berkeley, Denis Diderot, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Lord Monboddo, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, Hugo Grotius, and Voltaire.

Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by Hutcheson's protégés in Edinburgh: David Hume and Adam Smith.

[46] Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed a "science of man,"[47] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar, and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity.

Modern sociology largely originated from this movement,[48] and Hume's philosophical concepts that directly influenced James Madison (and thus the U.S. Constitution), and as popularised by Dugald Stewart was the basis of classical liberalism.

Some philosophes argued that the establishment of a contractual basis of rights would lead to the market mechanism and capitalism, the scientific method, religious tolerance, and the organization of states into self-governing republics through democratic means.

Frederick explained: "My principal occupation is to combat ignorance and prejudice... to enlighten minds, cultivate morality, and to make people as happy as it suits human nature, and as the means at my disposal permit.

For example, in France it became associated with anti-government and anti-Church radicalism, while in Germany it reached deep into the middle classes, where it expressed a spiritualistic and nationalistic tone without threatening governments or established churches.

[101] Freethinking, a term describing those who stood in opposition to the institution of the Church, and the literal belief in the Bible, can be said to have begun in England no later than 1713, when Anthony Collins wrote his "Discourse of Free-thinking," which gained substantial popularity.

Porter says the reason was that Enlightenment had come early to England and had succeeded such that the culture had accepted political liberalism, philosophical empiricism, and religious toleration, positions which intellectuals on the continent had to fight against powerful odds.

[136] Charles IV gave Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt free rein to travel in Spanish America, usually closed to foreigners, and more importantly, access to crown officials to aid the success of his scientific expedition.

She used her own interpretation of Enlightenment ideals, assisted by notable international experts such as Voltaire (by correspondence) and in residence world class scientists such as Leonhard Euler and Peter Simon Pallas.

[142] Enlightenment ideas (oświecenie) emerged late in Poland, as the Polish middle class was weaker and szlachta (nobility) culture (Sarmatism) together with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth political system (Golden Liberty) were in deep crisis.

They included King Stanislaw II August and reformers Piotr Switkowski, Antoni Poplawski, Josef Niemcewicz, and Jósef Pawlinkowski, as well as Baudouin de Cortenay, a Polonized dramatist.

"[2] During this time, ideals of Chinese society were reflected in "the reign of the Qing emperors Kangxi and Qianlong; China was posited as the incarnation of an enlightened and meritocratic society—and instrumentalized for criticisms of absolutist rule in Europe.

[146] Robert Bellah found "origins of modern Japan in certain strands of Confucian thinking, a 'functional analogue to the Protestant Ethic' that Max Weber singled out as the driving force behind Western capitalism.

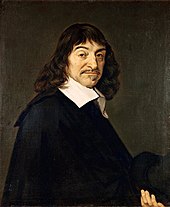

[161] There is little consensus on the precise beginning of the Age of Enlightenment, though several historians and philosophers argue that it was marked by Descartes' 1637 philosophy of Cogito, ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am"), which shifted the epistemological basis from external authority to internal certainty.

[169]Extending Horkheimer and Adorno's argument, intellectual historian Jason Josephson Storm argues that any idea of the Age of Enlightenment as a clearly defined period that is separate from the earlier Renaissance and later Romanticism or Counter-Enlightenment constitutes a myth.

Habermas said that the public sphere was bourgeois, egalitarian, rational, and independent from the state, making it the ideal venue for intellectuals to critically examine contemporary politics and society, away from the interference of established authority.

[174] Habermas uses the term "common concern" to describe those areas of political/social knowledge and discussion that were previously the exclusive territory of the state and religious authorities, now open to critical examination by the public sphere.

[199] According to Darnton, more importantly the Grub Street hacks inherited the "revolutionary spirit" once displayed by the philosophes and paved the way for the French Revolution by desacralizing figures of political, moral, and religious authority in France.

Developments in the Industrial Revolution allowed consumer goods to be produced in greater quantities at lower prices, encouraging the spread of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and journals – "media of the transmission of ideas and attitudes."

As shown by Matthew Daniel Eddy, natural history in this context was a very middle class pursuit and operated as a fertile trading zone for the interdisciplinary exchange of diverse scientific ideas.

Newton's celebrated Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica was published in Latin and remained inaccessible to readers without education in the classics until Enlightenment writers began to translate and analyze the text in the vernacular.

Extant records of subscribers show that women from a wide range of social standings purchased the book, indicating the growing number of scientifically inclined female readers among the middling class.

In addition to being conducive to Enlightenment ideologies of liberty, self-determination, and personal responsibility, it offered a practical theory of the mind that allowed teachers to transform longstanding forms of print and manuscript culture into effective graphic tools of learning for the lower and middle orders of society.

Indeed, although the "vast majority" of participants belonged to the wealthier strata of society ("the liberal arts, the clergy, the judiciary and the medical profession"), there were some cases of the popular classes submitting essays and even winning.

One of the most popular critiques of the coffeehouse said that it "allowed promiscuous association among people from different rungs of the social ladder, from the artisan to the aristocrat" and was therefore compared to Noah's Ark, receiving all types of animals, clean and unclean.

"[275] Scottish professor Thomas Munck argues that "although the Masons did promote international and cross-social contacts which were essentially non-religious and broadly in agreement with enlightened values, they can hardly be described as a major radical or reformist network in their own right.