Ethiopian historiography

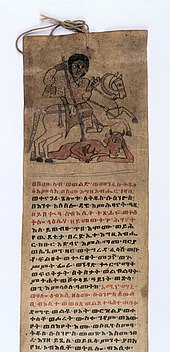

These early texts were written in either the Ethiopian Ge'ez script or the Greek alphabet, and included a variety of mediums such as manuscripts and epigraphic inscriptions on monumental stelae and obelisks documenting contemporary events.

Diplomatic ties with Christendom were established in the Roman era under Ethiopia's first Christian king, Ezana of Axum, in the 4th century AD, and were renewed in the Late Middle Ages with embassies traveling to and from medieval Europe.

These contacts and conflicts inspired works of ethnography, by authors such as the monk and historian Bahrey, which were embedded into the existing historiographic tradition and encouraged a broader view in historical chronicles for Ethiopia's place in the world.

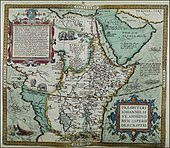

[3] The roots of the historiographic tradition in Ethiopia date back to the Aksumite period (c. 100 – c. 940 AD) and are found in epigraphic texts commissioned by monarchs to recount the deeds of their reign and royal house.

Written in an autobiographical style, in either the native Ge'ez script, the Greek alphabet, or both, they are preserved on stelae, thrones, and obelisks found in a wide geographical span that includes Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia.

For instance, 4th-century stelae erected by Ezana of Axum memorialize his achievements in battle and expansion of the realm in the Horn of Africa, while the Monumentum Adulitanum inscribed on a throne in Adulis, Eritrea, contains descriptions of an Aksumite king's conquests in the Red Sea region during the 3rd century, including parts of the Arabian peninsula.

[6] In Roman historiography, the ecclesiastical history of Tyrannius Rufinus, a Latin translation and extension of the work of Eusebius dated circa 402, offers an account of the Christian conversion of Ethiopia (labeled as "India ulterior") by the missionary Frumentius of Tyre.

[1] Cosmas Indicopleustes, a 6th-century Eastern Roman monk and former merchant who wrote the Christian Topography (describing the Indian Ocean trade leading all the way to China),[11] visited the Aksumite port city of Adulis and included eyewitness accounts of it in his book.

[12] He copied a Greek inscription detailing the reign of an early 3rd-century polytheistic ruler of Aksum who sent a naval fleet across the Red Sea to conquer the Sabaeans in what is now Yemen, along with other parts of western Arabia.

[22] Carlo Conti Rossini (1872–1949) hypothesized that she was an ethnic Sidamo from Damot, whereas Steven Kaplan argues she was a non-Christian invader and historian Knud Tage Andersen contends she was a regular member of the Aksumite royal house who shrewdly seized the throne.

[29] De Lorenzi compares the tome's mixture of Christian mythology with historical events to the legend of King Arthur that was greatly embellished by the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth in his chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae of 1136.

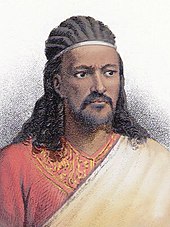

The royal biographical genre was established during the reign of Amda Seyon I (r. 1314–1344), whose biography not only recounted the diplomatic exchanges and military conflicts with the rival Islamic Ifat Sultanate, but also depicted the Ethiopian ruler as the Christian savior of his nation.

[32] For instance, the anonymously written biography of the emperor Gelawdewos (r. 1540–1549) speaks glowingly of the ruler, albeit in an elegiac tone, while attempting to place him and his deeds within a greater moral and historical context.

[35] Records of these contacts encouraged medieval Europeans to discover if Ethiopia was still Christian or had converted to Islam, an idea bolstered by the presence of Ethiopian pilgrims in the Holy Land and Jerusalem during the Crusades.

[36] During the High Middle Ages, the Mongol conquests of Genghis Khan (r. 1206–1227) led Europeans to speculate about the existence of a priestly, legendary warrior king named Prester John, who was thought to inhabit distant lands in Asia associated with Nestorian Christians and might help to defeat rival Islamic powers.

The travel literature of Marco Polo and Odoric of Pordenone regarding their separate journeys to Yuan-dynasty China during the 13th and 14th centuries, respectively, and fruitless searches in southern India, helped to dispel the notion that Prester John's kingdom existed in Asia.

[39] In his 1324 Book of Marvels the Dominican missionary Jordan Catala, bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon along the Malabar Coast of India, was the first known author to suggest that Ethiopia was the location of Prester John's kingdom.

[38] This was followed by the lengthy stay of Pietro Rombuldo in Ethiopia from 1404 to 1444 and Ethiopian diplomats attending the ecumenical Council of Florence in 1441, where they expressed some vexation with the European attendees who insisted on addressing their emperor as Prester John.

[44] The Mamluk-Egyptian historian Shihab al-Umari (1300–1349) wrote that the historical state of Bale, neighboring the Hadiya Sultanate of southern Ethiopia, was part of an Islamic Zeila confederacy, although it fell under the control of the Ethiopian Empire in the 1330s, during the reign of Amda Seyon I.

[46] He described other allegedly significant victories won by the Adal sultan Jamal ad-Din II (d. 1433) in Bale and Dawaro, where the Muslim leader was said to have taken enough war booty to provide his poorer subjects with multiple slaves.

Zhang Xiang, a scholar of Africa–China relations, asserts that the country of Dou le described in the Xiyu juan (i.e. Western Regions) chapter of the Book of Later Han was that of the Aksumite port city of Adulis.

[49] The 11th-century New Book of Tang and 14th-century Wenxian Tongkao describe the country of Nubia (previously controlled by the Aksumite Kingdom) as a land of deserts south of the Byzantine Empire that was infested with malaria, where the natives of the local Mo-lin territory had black skin and consumed foods such as Persian dates.

[49] During the 16th century the Ethiopian biographical tradition became far more complex, intertextual, and broader in its view of the world given Ethiopia's direct involvement in the conflicts between the Ottoman and Portuguese empires in the Red Sea region.

[63] The chaotic period known as the Era of the Princes (Zemene Mesafint) from the mid-18th to mid-19th centuries witnessed political fragmentation, civil war, loss of central authority, and, as a result of these, a complete shift away from the royal biography in favor of dynastic histories.

[67] Hanna Rubinkowska maintains that Emperor Selassie was an active proponent of "historiographic manipulation", especially when it came to concealing historical materials that seemingly contested or contradicted dynastic propaganda and official history.

[80] After Ludolf, the 18th-century Scottish travel writer James Bruce, who visited Ethiopia, and German orientalist August Dillmann (1823–1894) are also considered pioneers in the field of early Ethiopian studies.

[89] Gabra Heywat Baykadan, a foreign-educated historian and reformist intellectual during the reign of Menelik II (r. 1889–1913),[90] was unique among his peers for breaking almost entirely from the traditionalist approach to writing vernacular history and systematically adopting Western theoretical methods.

[91] Heruy Wolde Selassie (1878–1938), blattengeta and foreign minister of Ethiopia, used English scholarship and nominally adopted modern Western methods in writing vernacular history, but he was a firmly traditionalist historian.

[105] Following the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution and overthrow of the Solomonic dynasty with the deposition of Haile Selassie, the historical materialism of Marxist historiography came to dominate the academic landscape and understanding of Northeast African history.

[117] Zewde also observed that historiographic studies in Africa were centered on methods and schools that were primarily developed in Nigeria and Tanzania, and concluded that "the integration of Ethiopian historiography into the African mainstream, a perennial concern, is still far from being achieved to a satisfactory degree.