Flavin adenine dinucleotide

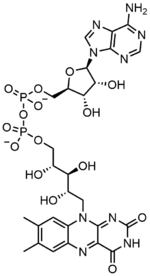

In biochemistry, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) is a redox-active coenzyme associated with various proteins, which is involved with several enzymatic reactions in metabolism.

[4] It took 50 years for the scientific community to make any substantial progress in identifying the molecules responsible for the yellow pigment.

The 1930s launched the field of coenzyme research with the publication of many flavin and nicotinamide derivative structures and their obligate roles in redox catalysis.

German scientists Otto Warburg and Walter Christian discovered a yeast derived yellow protein required for cellular respiration in 1932.

Theorell confirmed the pigment to be riboflavin's phosphate ester, flavin mononucleotide (FMN) in 1937, which was the first direct evidence for enzyme cofactors.

[7] This makes the dinucleotide name misleading; however, the flavin mononucleotide group is still very close to a nucleotide in its structure and chemical properties.

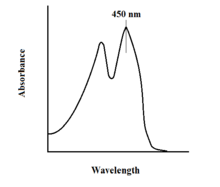

[citation needed] The spectroscopic properties of FAD and its variants allows for reaction monitoring by use of UV-VIS absorption and fluorescence spectroscopies.

Each form of FAD has distinct absorbance spectra, making for easy observation of changes in oxidation state.

This property can be utilized when examining protein binding, observing loss of fluorescent activity when put into the bound state.

FAD plays a major role as an enzyme cofactor along with flavin mononucleotide, another molecule originating from riboflavin.

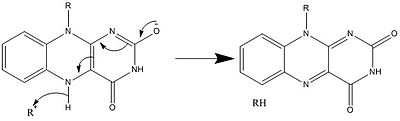

[11] Flavoproteins utilize the unique and versatile structure of flavin moieties to catalyze difficult redox reactions.

Since flavins have multiple redox states they can participate in processes that involve the transfer of either one or two electrons, hydrogen atoms, or hydronium ions.

[16] FAD is the more complex and abundant form of flavin and is reported to bind to 75% of the total flavoproteome[16] and 84% of human encoded flavoproteins.

[17] Cellular concentrations of free or non-covalently bound flavins in a variety of cultured mammalian cell lines were reported for FAD (2.2-17.0 amol/cell) and FMN (0.46-3.4 amol/cell).

The cell utilizes this in many energetically difficult oxidation reactions such as dehydrogenation of a C-C bond to an alkene.

FAD-dependent proteins function in a large variety of metabolic pathways including electron transport, DNA repair, nucleotide biosynthesis, beta-oxidation of fatty acids, amino acid catabolism, as well as synthesis of other cofactors such as CoA, CoQ and heme groups.

One well-known reaction is part of the citric acid cycle (also known as the TCA or Krebs cycle); succinate dehydrogenase (complex II in the electron transport chain) requires covalently bound FAD to catalyze the oxidation of succinate to fumarate by coupling it with the reduction of ubiquinone to ubiquinol.

[20] Additional examples of FAD-dependent enzymes that regulate metabolism are glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (triglyceride synthesis) and xanthine oxidase involved in purine nucleotide catabolism.

[16] Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is an extensively studied flavoenzyme due to its biological importance with the catabolism of norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine.

MAO oxidizes primary, secondary and tertiary amines, which nonenzymatically hydrolyze from the imine to aldehyde or ketone.

[23] Glucose oxidase (GOX) catalyzes the oxidation of β-D-glucose to D-glucono-δ-lactone with the simultaneous reduction of enzyme-bound flavin.

[23] UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvylglucosamine Reductase (MurB) is an enzyme that catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of enolpyruvyl-UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (substrate) to the corresponding D-lactyl compound UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid (product).

[23] Cytochrome P450 type enzymes that catalyze monooxygenase (hydroxylation) reactions are dependent on the transfer of two electrons from FAD to the P450.

[17] In some cases, this is due to a decreased affinity for FAD or FMN and so excess riboflavin intake may lessen disease symptoms, such as for multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency.

[9] Both of these paths can result in a variety of symptoms, including developmental or gastrointestinal abnormalities, faulty fat break-down, anemia, neurological problems, cancer or heart disease, migraine, worsened vision and skin lesions.

[28] Already, scientists have determined the two structures FAD usually assumes once bound: either an extended or a butterfly conformation, in which the molecule essentially folds in half, resulting in the stacking of the adenine and isoalloxazine rings.

[14] FAD imitators that are able to bind in a similar manner but do not permit protein function could be useful mechanisms of inhibiting bacterial infection.

[30] The field has advanced in recent years with a number of new tools, including those to trigger light sensitivity, such as the Blue-Light-Utilizing FAD domains (BLUF).

[30] Similar to other photoreceptors, the light causes structural changes in the BLUF domain that results in disruption of downstream interactions.

[30] There are a number of molecules in the body that have native fluorescence including tryptophan, collagen, FAD, NADH and porphyrins.