Facultative anaerobic organism

[1][2] Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are Staphylococcus spp.,[3] Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Listeria spp.,[4] Shewanella oneidensis and Yersinia pestis.

[6] It has been observed that in mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that underwent mutations to be either obligate aerobes or anaerobes, there were varying levels of chromatin-remodeling proteins.

[8][9] There may exist a core network of transcription factors (TFs) that includes the major oxygen-responsive ArcA and FNR control the adaptation of Escherichia coli to changes in oxygen availability.

[11] For example, in the absence of oxygen, E. coli can use fumarate, nitrate, nitrite, dimethyl sulfoxide, or trimethylamine oxide as an electron acceptor.

[12] Since facultative anaerobes can grow in both the presence and absence of oxygen, they can survive in many different environments, adapt easily to changing conditions, and thus have a selective advantage over other bacteria.

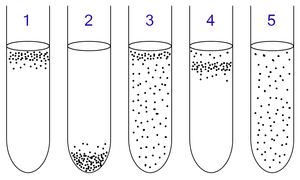

1: Obligate aerobes need oxygen because they cannot ferment or respire anaerobically . They gather at the top of the tube where the oxygen concentration is highest.

2: Obligate anaerobes are poisoned by oxygen, so they gather at the bottom of the tube where the oxygen concentration is lowest.

3: Facultative anaerobes can grow with or without oxygen because they can metabolise energy aerobically or anaerobically. They gather mostly at the top because aerobic respiration generates more ATP than fermentation.

4: Microaerophiles need oxygen because they cannot ferment or respire anaerobically. However, they are poisoned by high concentrations of oxygen. They gather in the upper part of the test tube but not the very top.

5: Aerotolerant anaerobes do not require oxygen as they use fermentation to make ATP. Unlike obligate anaerobes, they are not poisoned by oxygen. They can be found evenly spread throughout the test tube.