Iron(III) chloride

Although Fe(III) chloride can be octahedral or tetrahedral (or both, see structure section), all of these forms have five unpaired electrons, one per d-orbital.

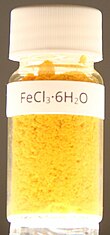

[8][9] Iron(III) chloride can exist as an anhydrous material and a series of hydrates, which results in distinct structures.

This dimer dissociates into the monomeric FeCl3 (with D3h point group molecular symmetry) at higher temperatures, in competition with its reversible decomposition to give iron(II) chloride and chlorine gas.

This cation can adopt either trans or cis stereochemistry, reflecting the relative location of the chloride ligands on the octahedral Fe center.

These species differ with respect to the stereochemistry of the octahedral iron cation, the identity of the anions, and the presence or absence of water of crystallization.

[9] Detailed speciation of aqueous solutions of ferric chloride is challenging because the individual components do not have distinctive spectroscopic signatures.

Iron(III) complexes, with a high spin d5 configuration, is kinetically labile, which means that ligands rapidly dissociate and reassociate.

Dilute solutions of ferric chloride produce soluble nanoparticles with molecular weight of 104, which exhibit the property of "aging", i.e., the structure change or evolve over the course of days.

The principal method, called direct chlorination, uses scrap iron as a precursor:[10] The reaction is conducted at several hundred degrees such that the product is gaseous.

[9][19] In contrast to their kinetic lability, iron(III) chlorides are thermodynamically robust, as reflected by the vigorous methods applied to their synthesis, as described above.

[20] Reactions of anhydrous iron(III) chloride reflect its description as both oxophilic and a hard Lewis acid.

[22][23] In the solid phase a variety of multinuclear complexes have been described for the nominal stoichiometric reaction between FeCl3 and sodium ethoxide: Iron(III) chloride forms a 1:2 adduct with Lewis bases such as triphenylphosphine oxide; e.g., FeCl3(OP(C6H5)3)2.

For example, oxalate salts react rapidly with aqueous iron(III) chloride to give [Fe(C2O4)3]3−, known as ferrioxalate.

These studies are enabled because of the solubility of FeCl3 in ethereal solvents, which avoids the possibility of hydrolysis of the nucleophilic alkylating agents.

[29] Illustrating the sensitivity of these reactions, methyl lithium LiCH3 reacts with iron(III) chloride to give lithium tetrachloroferrate(II) Li2[FeCl4]:[30] To a significant extent, iron(III) acetylacetonate and related beta-diketonate complexes are more widely used than FeCl3 as ether-soluble sources of ferric ion.

[20] These diketonate complexes have the advantages that they do not form hydrates, unlike iron(III) chloride, and they are more soluble in relevant solvents.

By forming highly dispersed networks of Fe-O-Fe containing materials, ferric chlorides serve as coagulant and flocculants.

[33] In this application, an aqueous solution of FeCl3 is treated with base to form a floc of iron(III) hydroxide (Fe(OH)3), also formulated as FeO(OH) (ferrihydrite).

[44] Illustrating it use as a Lewis acid, iron(III) chloride catalyses electrophilic aromatic substitution and chlorinations.

[45] Although iron(III) chlorides are seldom used in practical organic synthesis, they have received considerable attention as reagents because they are inexpensive, earth abundant, and relatively nontoxic.

[56][57] Iron(III) chlorides are widely used in the treatment of drinking water,[10] so they pose few problems as poisons, at low concentrations.

Nonetheless, anhydrous iron(III) chloride, as well as concentrated FeCl3 aqueous solution, is highly corrosive, and must be handled using proper protective equipment.