Nuclear weapon

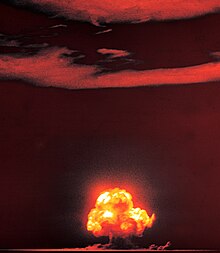

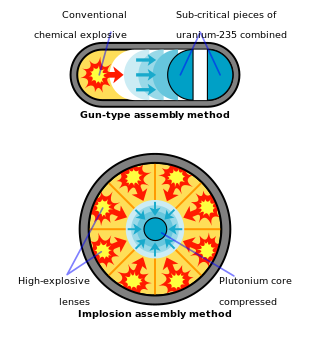

On August 6, 1945, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) detonated a uranium gun-type fission bomb nicknamed "Little Boy" over the Japanese city of Hiroshima; three days later, on August 9, the USAAF[3] detonated a plutonium implosion-type fission bomb nicknamed "Fat Man" over the Japanese city of Nagasaki.

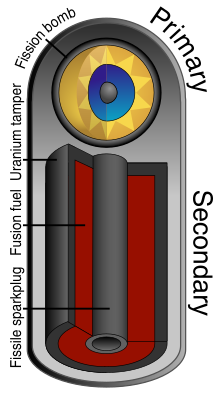

Almost all of the nuclear weapons deployed today use the thermonuclear design because it results in an explosion hundreds of times stronger than that of a fission bomb of similar weight.

The ensuing fusion reaction creates enormous numbers of high-speed neutrons, which can then induce fission in materials not normally prone to it, such as depleted uranium.

This is in contrast to fission bombs, which are limited in their explosive power due to criticality danger (premature nuclear chain reaction caused by too-large amounts of pre-assembled fissile fuel).

Furthermore, high yield thermonuclear explosions (most dangerously ground bursts) have the force to lift radioactive debris upwards past the tropopause into the stratosphere, where the calm non-turbulent winds permit the debris to travel great distances from the burst, eventually settling and unpredictably contaminating areas far removed from the target of the explosion.

The external method of boosting enabled the USSR to field the first partially thermonuclear weapons, but it is now obsolete because it demands a spherical bomb geometry, which was adequate during the 1950s arms race when bomber aircraft were the only available delivery vehicles.

It has been conjectured that such a device could serve as a "doomsday weapon" because such a large quantity of radioactivities with half-lives of decades, lifted into the stratosphere where winds would distribute it around the globe, would make all life on the planet extinct.

In connection with the Strategic Defense Initiative, research into the nuclear pumped laser was conducted under the DOD program Project Excalibur but this did not result in a working weapon.

Mechanisms to release this energy as bursts of gamma radiation (as in the hafnium controversy) have been proposed as possible triggers for conventional thermonuclear reactions.

[25] However, the US Air Force funded studies of the physics of antimatter in the Cold War, and began considering its possible use in weapons, not just as a trigger, but as the explosive itself.

Such a weapon could, according to tacticians, be used to cause massive biological casualties while leaving inanimate infrastructure mostly intact and creating minimal fallout.

[11][29] Preferable from a strategic point of view is a nuclear weapon mounted on a missile, which can use a ballistic trajectory to deliver the warhead over the horizon.

[11] Tactical weapons have involved the most variety of delivery types, including not only gravity bombs and missiles but also artillery shells, land mines, and nuclear depth charges and torpedoes for anti-submarine warfare.

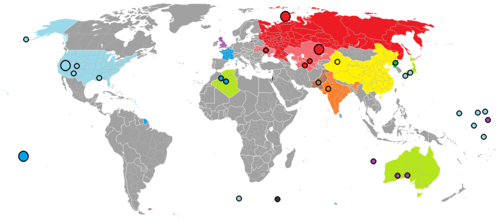

Some prominent neo-realist scholars, such as Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer, have argued, along the lines of Gallois, that some forms of nuclear proliferation would decrease the likelihood of total war, especially in troubled regions of the world where there exists a single nuclear-weapon state.

[33][34] Interest in proliferation and the stability-instability paradox that it generates continues to this day, with ongoing debate about indigenous Japanese and South Korean nuclear deterrent against North Korea.

It has been argued, especially after the September 11, 2001, attacks, that this complication calls for a new nuclear strategy, one that is distinct from that which gave relative stability during the Cold War.

[c] Despite controls and regulations governing nuclear weapons, there is an inherent danger of "accidents, mistakes, false alarms, blackmail, theft, and sabotage".

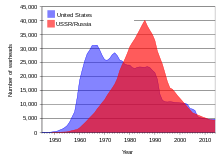

[42] In the late 1940s, lack of mutual trust prevented the United States and the Soviet Union from making progress on arms control agreements.

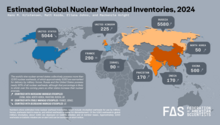

Even when they did not enter into force, these agreements helped limit and later reduce the numbers and types of nuclear weapons between the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia.

The two years with the highest likelihood had previously been 1953, when the Clock was set to two minutes until midnight after the US and the Soviet Union began testing hydrogen bombs, and 2018, following the failure of world leaders to address tensions relating to nuclear weapons and climate change issues.

The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has as one of its explicit conditions that all signatories must "pursue negotiations in good faith" towards the long-term goal of "complete disarmament".

In January 2010, Lawrence M. Krauss stated that "no issue carries more importance to the long-term health and security of humanity than the effort to reduce, and perhaps one day, rid the world of nuclear weapons".

[54] In January 1986, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev publicly proposed a three-stage program for abolishing the world's nuclear weapons by the end of the 20th century.

[57] Some analysts have argued that nuclear weapons have made the world relatively safer, with peace through deterrence and through the stability–instability paradox, including in south Asia.

The climatology hypothesis is that if each city firestorms, a great deal of soot could be thrown up into the atmosphere which could blanket the earth, cutting out sunlight for years on end, causing the disruption of food chains, in what is termed a nuclear winter.

[91][92] Staying indoors until after the most hazardous fallout isotope, I-131 decays away to 0.1% of its initial quantity after ten half-lifes—which is represented by 80 days in I-131s case, would make the difference between likely contracting Thyroid cancer or escaping completely from this substance depending on the actions of the individual.

[101] In the United Kingdom, the Aldermaston Marches organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) took place at Easter 1958, when, according to the CND, several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.

[104] In 1962, Linus Pauling won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to stop the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the "Ban the Bomb" movement spread.

In August 1939, concerned that Germany might have its own project to develop fission-based weapons, Albert Einstein signed a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him of the threat.

The Maud Committee was set up following the work of Frisch and Rudolf Peierls who calculated uranium-235's critical mass and found it to be much smaller than previously thought which meant that a deliverable bomb should be possible.