Geomicrobiology

It concerns the role of microbes on geological and geochemical processes and effects of minerals and metals to microbial growth, activity and survival.

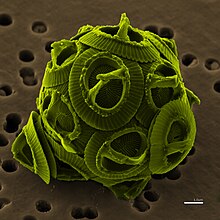

[3] Geomicrobiology studies microorganisms that are driving the Earth's biogeochemical cycles, mediating mineral precipitation and dissolution, and sorbing and concentrating metals.

Biohydrometallurgy or in situ mining is where low-grade ores may be attacked by well-studied microbial processes under controlled conditions to extract metals.

Thirteen metals are considered priority pollutants (Sb, As, Be, Cd, Cr, Cu, Pb, Ni, Se, Ag, Tl, Zn, Hg).

Studies have shown that the production of bicarbonate by microbes such as sulfate-reducing bacteria adds alkalinity to neutralize the acidity of the mine drainage waters.

Various rock-water interactions, such as serpentinization and water radiolysis,[12] are possible sources of metabolic energy to support chemolithoautotrophic microbial communities on Early Earth and on other planetary bodies such as Mars, Europa and Enceladus.

Information on the life during Archean Earth is recorded in bacterial fossils and stromatolites preserved in precipitated lithologies such as chert or carbonates.

They are formed by the interaction of microbial mats and physical sediment dynamics, and record paleoenvironmental data as well as providing evidence of early life.

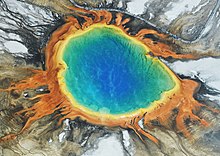

Another area of investigation in geomicrobiology is the study of extremophile organisms, the microorganisms that thrive in environments normally considered hostile to life.

[27] This suggests the alteration and replacement of limestone sediments by dolomitization in ancient rocks was possibly aided by ancestors to these anaerobic bacteria.

[28] In July 2019, a scientific study of Kidd Mine in Canada discovered sulfur-breathing organisms which live 7900 feet below the surface, and which breathe sulfur in order to survive.