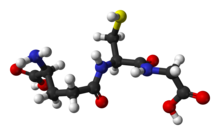

Glutathione

GCLC knockout mice die within a month of birth due to the absence of hepatic GSH synthesis.

[6] The concentration of glutathione in the cytoplasm is significantly higher (ranging from 0.5-10 mM) compared to extracellular fluids (2-20 μM), reaching levels up to 1000 times greater.

[10] Human beings synthesize glutathione, but a few eukaryotes do not, including some members of Fabaceae, Entamoeba, and Giardia.

It had low bioavailability because the tripeptide is the substrate of proteases (peptidases) of the alimentary canal, and due to the absence of a specific carrier of glutathione at the level of cell membrane.

[18] This conversion is catalyzed by glutathione reductase: GSH protects cells by neutralising (reducing) reactive oxygen species.

The general reaction involves formation of an unsymmetrical disulfide from the protectable protein (RSH) and GSH:[20] Glutathione is also employed for the detoxification of methylglyoxal and formaldehyde, toxic metabolites produced under oxidative stress.

Glutathione S-transferase enzymes catalyze its conjugation to lipophilic xenobiotics, facilitating their excretion or further metabolism.

[29] Glutathione is required for efficient defence against plant pathogens such as Pseudomonas syringae and Phytophthora brassicae.

[32] Thus, drug delivery systems containing disulfide bonds, typically cross-linked micro-nanogels, stand out for their ability to degrade in the presence of high concentrations of glutathione (GSH).

[33] This degradation process releases the drug payload specifically into cancerous or tumorous tissue, leveraging the significant difference in redox potential between the oxidizing extracellular environment and the reducing intracellular cytosol.

GSH, a potent reducing agent, donates electrons to disulfide bonds in the nanogels, initiating a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction.

This reaction breaks the disulfide bonds, converting them into two thiol groups, and facilitates targeted drug release where it is needed most.