Gothic aspects in Frankenstein

When Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published in 1818, the novel immediately found itself labeled as Gothic and, with a few exceptions, promoted to the status of masterpiece.

Coleridge, familiar with the Godwins and thus with Mary Shelley, wrote as early as 1797, in reference to M. G. Lewis's The Monk, that "the horrible and the supernatural [...], powerful stimulants, are never required, unless for the torpor of a drowsy or exhausted appetite".

"[4] In Northanger Abbey, Jane Austen, in 1817, had Henry Tilney give Catherine Morland a lesson in common sense:[5] "Remember that we are English, that we are Christian.

The great Gothic wave, which stretches from 1764 with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto to around 1818-1820, features ghosts, castles and terrifying characters; Satanism and the supernatural are favorite subjects; for instance, Ann Radcliffe presents sensitive, persecuted young girls who evolve in a frightening universe where secret doors open onto visions of horror, themes even more clearly addressed by M. G. Lewis at the age of twenty.

"[1] The first great gothic wave based its effects on what was more commonly referred to as "terror", the desired feeling being "fear" or " fright" (frayeur),[11] hence the use of well-known devices, which Max Duperray calls "a machinery to frighten.

"[1] There are still many hints of this in Frankenstein: Victor works in a secret laboratory plunged into darkness; his somewhat remote house is streaked with labyrinthine corridors; he enters, without describing them, into forbidden vaults, he breaks into cemeteries soon to be profaned; the mountains he climbs are pierced by sinister caves, icy spaces stretch to infinity, lands and oceans tumble into chaos, etc.

[14] Moreover, Victor Frankenstein is careful to point out that his education has rid him of all prejudice, that the supernatural holds no appeal for him, in short that his knowledge and natural disposition lead him along the enlightened path of rationalism.

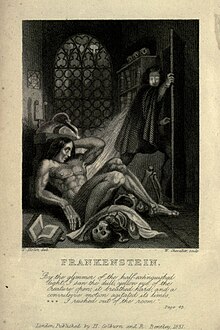

[16] What's more, the horror comes to life in the figure of the monster who, although alive, has lost none of his cadaverous characteristics, and it's this complacently supported description of his physical appearance that is one of the driving forces behind the action, since it provokes social rejection, hence revenge, the reversal of the situation, and so on.

The horror of the eyes, eyelids, cheeks, lips, colors, mummification, open body, functional organs but gangrenous and infested with morbid decay, is further accentuated by the unfinished making of a female creature: although not explicitly stated, the text suggests that it is precisely at the moment when the woman's genitals are to be placed that Victor's rage leads him to lacerate, tear, destroy, restore the assembled shreds to chaos.

[17] Frankenstein's work unleashes into the world of men a creature of gigantic hideousness, scruffy, cadaverous, and it stops when it was not far from finding its fulfillment in the possibility of a monstrous lineage.

Moreover, Victor is presented as a relentless, obstinate researcher, whose intellectual activity is clearly compartmentalized: nothing else interests him, literary and artistic culture, the so-called moral sciences being left to Clerval.

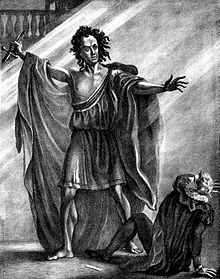

[21] Once the act of creation is complete, the Gothic aspect of the novel leaves the stage of the outside world - with the exception of a few appearances by the monster and the repetition of Chapter V when the female creature is made again - to confine itself to the mysteries of the psyche: this exploration focuses primarily on Victor, but also takes into account the analysis of the monster by itself, in the central section devoted to his apology and at the end, during the ultimate encounter with Walton next to Frankenstein's corpse.

[22] The despicable or the sublime emanate, as Saint-Girons notes in his preface to Burke's work, from states of mind most often subject to exhausting existential anguish, linked to isolation, feelings of guilt and also manifestations of the unconscious.

The scientific changes, the creative act of Victor Frankenstein, are a matter for the imagination, that faculty of the Romantic artist who has freed himself from the straitjacket of the rules of composition, writing, poetic language and propriety.

The hero's transgressive personality becomes villainous:[32] the reader is placed in a world whose equilibrium is disrupted, which collapses and self-destructs; legal institutions explode, the innocent are executed, the falsely guilty are arrested; the very republic is threatened as its leaders, the syndics of the city of Geneva, find themselves destabilized, then annihilated.

Even nature seems to express its indignation and wrath: the peaks become menacing, the ice becomes chaotic and frail,[28] boats are seized and then drift away (like people), the peaceful Rhine valley opens onto the lunar, the planet has become hostile, as if subject to evil spells.

[36] The demon that torments Victor seems to be love, but with it the Map of tender becomes macabre, the plain of desire littered with corpses, right from the seminal dream of the kiss of death.

[42] Frankenstein brings the genre to its apogee, but heralds its death with its overly tranquil trajectory: it will have been secularized, rid of the miraculous; its fantastic is explained and, above all, recognized as a constituent part of man; the reader is enclosed within a framework of rationality.

"[22] The characters are often wealthy notables, always refined and enamored of good manners, indulging in the delights of cultural tourism, not prone to rambling, regretting the unorthodox choices of Clerval's studies, too inclined towards orientalism.

[50] The novel, situated under the sign of ambiguity and tension, is therefore paradoxical, just as is a genre that has reached the limits of its expressive possibilities and, with Frankenstein, tips over into the Romantic realm.

In fact, insofar as, despite its exaggerations, its linearity, its total lack of verisimilitude, its theoretical substratum and its literary references, this work carves meaning out of human reality, it contains a dose of realism.