Guiding center

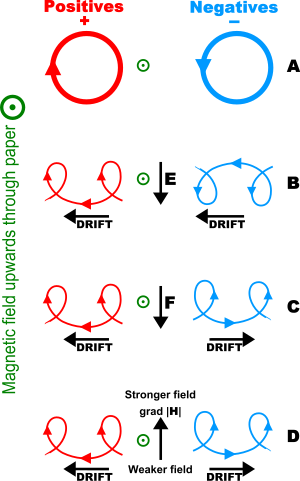

In physics, the motion of an electrically charged particle such as an electron or ion in a plasma in a magnetic field can be treated as the superposition of a relatively fast circular motion around a point called the guiding center and a relatively slow drift of this point.

The drift speeds may differ for various species depending on their charge states, masses, or temperatures, possibly resulting in electric currents or chemical separation.

If the magnetic field is uniform and all other forces are absent, then the Lorentz force will cause a particle to undergo a constant acceleration perpendicular to both the particle velocity and the magnetic field.

This does not affect particle motion parallel to the magnetic field, but results in circular motion at constant speed in the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field.

In a uniform field with no additional forces, a charged particle will gyrate around the magnetic field according to the perpendicular component of its velocity and drift parallel to the field according to its initial parallel velocity, resulting in a helical orbit.

If there is a force with a parallel component, the particle and its guiding center will be correspondingly accelerated.

While it is closely related to guiding center drifts in its physics and mathematics, it is nevertheless considered to be distinct from them.

Generally speaking, when there is a force on the particles perpendicular to the magnetic field, then they drift in a direction perpendicular to both the force and the field.

These drifts, in contrast to the mirror effect and the non-uniform B drifts, do not depend on finite Larmor radius, but are also present in cold plasmas.

Once the particle is moving in the drift direction, the magnetic field deflects it back against the external force, so that the average acceleration in the direction of the force is zero.

More generally, the superposition of a gyration and a uniform perpendicular drift is a trochoid.

The grad-B drift can be considered to result from the force on a magnetic dipole in a field gradient.

The curvature, inertia, and polarisation drifts result from treating the acceleration of the particle as fictitious forces.

The diamagnetic drift can be derived from the force due to a pressure gradient.

Finally, other forces such as radiation pressure and collisions also result in drifts.

A simple example of a force drift is a plasma in a gravitational field, e.g. the ionosphere.

The dependence on the charge of the particle implies that the drift direction is opposite for ions as for electrons, resulting in a current.

As a result, ions (of whatever mass and charge) and electrons both move in the same direction at the same speed, so there is no net current (assuming quasineutrality of the plasma).

In the context of special relativity, in the frame moving with this velocity, the electric field vanishes.

If the electric field is not uniform, the above formula is modified to read[2]

Guiding center drifts may also result not only from external forces but also from non-uniformities in the magnetic field.

It is convenient to express these drifts in terms of the parallel and perpendicular kinetic energies

In order for a charged particle to follow a curved field line, it needs a drift velocity out of the plane of curvature to provide the necessary centripetal force.

In the important limit of stationary magnetic field and weak electric field, the inertial drift is dominated by the curvature drift term.

In the limit of small plasma pressure, Maxwell's equations provide a relationship between gradient and curvature that allows the corresponding drifts to be combined as follows

In cylindrical coordinates chosen such that the azimuthal direction is parallel to the magnetic field and the radial direction is parallel to the gradient of the field, this becomes

Normally an oscillatory electric field results in a polarization drift oscillating 90 degrees out of phase.

Because of the mass dependence, this effect is also called the inertia drift.

Normally the polarization drift can be neglected for electrons because of their relatively small mass.

Nevertheless, the fluid velocity is defined by counting the particles moving through a reference area, and a pressure gradient results in more particles in one direction than in the other.