Hamilton's principle

It states that the dynamics of a physical system are determined by a variational problem for a functional based on a single function, the Lagrangian, which may contain all physical information concerning the system and the forces acting on it.

The variational problem is equivalent to and allows for the derivation of the differential equations of motion of the physical system.

Although formulated originally for classical mechanics, Hamilton's principle also applies to classical fields such as the electromagnetic and gravitational fields, and plays an important role in quantum mechanics, quantum field theory and criticality theories.

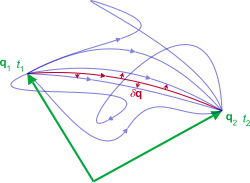

Hamilton's principle states that the true evolution q(t) of a system described by N generalized coordinates q = (q1, q2, ..., qN) between two specified states q1 = q(t1) and q2 = q(t2) at two specified times t1 and t2 is a stationary point (a point where the variation is zero) of the action functional

In other words, any first-order perturbation of the true evolution results in (at most) second-order changes in

In terms of functional analysis, Hamilton's principle states that the true evolution of a physical system is a solution of the functional equation

That is, the system takes a path in configuration space for which the action is stationary, with fixed boundary conditions at the beginning and the end of the path.

Requiring that the true trajectory q(t) be a stationary point of the action functional

Let q(t) represent the true evolution of the system between two specified states q1 = q(t1) and q2 = q(t2) at two specified times t1 and t2, and let ε(t) be a small perturbation that is zero at the endpoints of the trajectory

To first order in the perturbation ε(t), the change in the action functional

is zero for all possible perturbations ε(t), i.e., the true path is a stationary point of the action functional

The conjugate momentum pk for a generalized coordinate qk is defined by the equation

An important special case of the Euler–Lagrange equation occurs when L does not contain a generalized coordinate qk explicitly,

For example, if we use polar coordinates t, r, θ to describe the planar motion of a particle, and if L does not depend on θ, the conjugate momentum is the conserved angular momentum.

Trivial examples help to appreciate the use of the action principle via the Euler–Lagrange equations.

A free particle (mass m and velocity v) in Euclidean space moves in a straight line.

In the absence of a potential, the Lagrangian is simply equal to the kinetic energy

in orthonormal (x,y) coordinates, where the dot represents differentiation with respect to the curve parameter (usually the time, t).

In polar coordinates (r, φ) the kinetic energy and hence the Lagrangian becomes

Thus, indeed, the solution is a straight line given in polar coordinates: a is the velocity, c is the distance of the closest approach to the origin, and d is the angle of motion.

As opposed to a system composed of rigid bodies, deformable bodies have an infinite number of degrees of freedom and occupy continuous regions of space; consequently, the state of the system is described by using continuous functions of space and time.

If the system is conservative, the work done by external forces may be derived from a scalar potential V. In this case,

This is called Hamilton's principle and it is invariant under coordinate transformations.

They differ in three important ways: The action principle can be extended to obtain the equations of motion for fields, such as the electromagnetic field or gravity.

The Einstein equation utilizes the Einstein–Hilbert action as constrained by a variational principle.

The path of a body in a gravitational field (i.e. free fall in space time, a so-called geodesic) can be found using the action principle.

In quantum mechanics, the system does not follow a single path whose action is stationary, but the behavior of the system depends on all imaginable paths and the value of their action.

Although equivalent in classical mechanics with Newton's laws, the action principle is better suited for generalizations and plays an important role in modern physics.

Richard Feynman's path integral formulation of quantum mechanics is based on a stationary-action principle, using path integrals.

Maxwell's equations can be derived as conditions of stationary action.