Heidelberg School

[1] Melbourne art critic Sidney Dickinson coined the term in an 1891 review of works by Arthur Streeton and Walter Withers, two local artists who painted en plein air in Heidelberg on the city's rural outskirts.

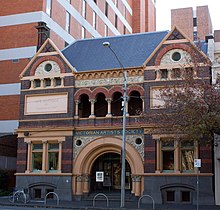

In August 1889, several artists of the Heidelberg School staged their first independent exhibition at Buxton's Rooms, Swanston Street, opposite the Melbourne Town Hall.

[3] The Japonist décor they chose for Buxton's Rooms featured Japanese screens, silk draperies, umbrellas, and vases with flowers that perfumed the gallery, while background music was performed on certain afternoons.

So, in these works, it has been the object of the artists to render faithfully, and thus obtain first records of effects widely differing, and often of very fleeting character.The exhibition caused a stir during its three-week run with Melbourne society "[flocking] to Buxton’s, hoping to be amazed, intrigued or outraged".

The most scathing review came from James Smith, then Australia's foremost art critic, who said the 9 by 5s were "destitute of all sense of the beautiful" and "whatever influence [the exhibition] was likely to exercise could scarcely be otherwise than misleading and pernicious.

"[8] The artists nailed the review to the entrance of the venue—attracting many more passing pedestrians to, in Streeton's words, "see the dreadful paintings"—and responded with a letter to the Editor of Smith's newspaper, The Argus.

Described as a manifesto, the letter defends freedom of choice in subject and technique, concluding: It is better to give our own idea than to get a merely superficial effect, which is apt to be a repetition of what others have done before us, and may shelter us in a safe mediocrity, which, while it will not attract condemnation, could never help towards the development of what we believe will be a great school of painting in Australia.

Grosvenor Chambers quickly became the focal point of Melbourne's art scene, with Conder, Streeton, McCubbin, Louis Abrahams and John Mather also moving in.

Throughout the 1890s, Fox and Tudor St. George Tucker ran the Melbourne School of Art at Charterisville, teaching plein airism and impressionist techniques to a new generation of artists, including Ina Gregory, Violet Teague and Hugh Ramsay.

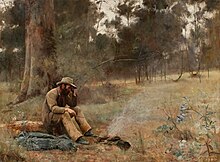

They were committed plein airists who sought to depict daily life, showed a keen interest in transient light and its effect on colour, and experimented with loose brushwork.

Indeed, the Heidelberg School artists did not espouse any colour theory, and, like another main influence of theirs, Jules Bastien-Lepage, often maintained a realist sense of form, clarity and composition.

Much of what they knew of French impressionism was through correspondence with painter John Russell, an Australian expatriate in France who befriended, and painted alongside the likes of Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet.

[21] They greatly admired the light-infused landscapes of Louis Buvelot, a Swiss-born artist and art teacher who, in the 1860s, adapted French Barbizon School principles to the countryside around Melbourne.

Regarding Buvelot as "the father of Australian landscape painting", they showed little interest in the works of earlier colonial artists, which they likened to European scenes that did not reflect Australia's harsh sunlight, earthier colours and distinctive vegetation.

The Heidelberg School painters spoke of seeing Australia "through Australian eyes", and by 1889, Roberts argued that they had successfully developed "a distinct and vital and creditable style".

They responded strongly to poet Adam Lindsay Gordon's emotional, sensorial evocations of the Australian landscape, both illustrating his work directly and using it as the basis for the titles of other paintings.

[28] By this time, Australia's leading art institutions had fully embraced the movement's style and pastoral vision, while simultaneously shunning the modernist innovations of more recent Australian artists, such as Clarice Beckett, Roy De Maistre and Grace Cossington Smith.

Even until the early 1940s, winning entries of the prestigious Wynne Prize, awarded annually by the Art Gallery of New South Wales for "the best landscape painting of Australian scenery", "invariably depicted the gum trees, sunlight and rural scene as developed by Streeton and Roberts".

[29] Heidelberg School member Walter Withers won the inaugural Wynne Prize in 1897 with The Storm, and leading successors of the movement, Elioth Gruner and Hans Heysen, went on to win a record seven and nine times, respectively.

According to Robert Hughes, the Heidelberg School tradition "ossified" during this period into a rigid academic system and an unimaginative national style prolonged by what he called its "zombie acolytes".

[39] The Getting of Wisdom (1977) and My Brilliant Career (1979) each found inspiration in the Heidelberg School;[37] outback scenes in the latter allude directly to works by Streeton, such as The Selector's Hut.

[44] The notion that the Heidelberg School painters were the first to objectively capture Australia's "scrubby bush" gained widespread acceptance in the early 20th century, but has since been disputed; for example, in the 1960s art historian Bernard Smith identified "an authentic bush atmosphere" in John Lewin's landscapes of the 1810s,[45] and John Glover in the 1830s is seen to have faithfully rendered Australia's unique light and sprawling, untidy gum trees.

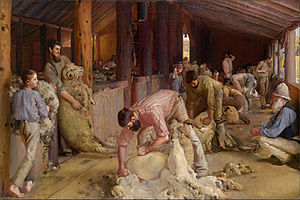

[46] Another longstanding assumption has been that the Heidelberg School was groundbreaking in its choice of local themes and subjects, creating a nationalistic iconography centered on shearers, drovers, swagmen, and other rural figures.