Heliocentrism

[b] It was not until the 16th century that a mathematical model of a heliocentric system was presented by the Renaissance mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic cleric, Nicolaus Copernicus, leading to the Copernican Revolution.

The second of the references by Plutarch is in his Platonic Questions:[19] Did Plato put the earth in motion, as he did the sun, the moon, and the five planets, which he called the instruments of time on account of their turnings, and was it necessary to conceive that the earth "which is globed about the axis stretched from pole to pole through the whole universe" was not represented as being held together and at rest, but as turning and revolving (στρεφομένην καὶ ἀνειλουμένην), as Aristarchus and Seleucus afterwards maintained that it did, the former stating this as only a hypothesis (ὑποτιθέμενος μόνον), the latter as a definite opinion (καὶ ἀποφαινόμενος)?The remaining references to Aristarchus' heliocentrism are extremely brief, and provide no more information beyond what can be gleaned from those already cited.

In Roman Carthage, the pagan Martianus Capella (5th century AD) expressed the opinion that the planets Venus and Mercury did not go about the Earth but instead circled the Sun.

[39][40] According to later astronomer al-Biruni, al-Sijzi invented an astrolabe called al-zūraqī based on a belief held by some of his contemporaries that the apparent motion of the stars was due to the Earth's movement, and not that of the firmament.

[29] In the 14th century, bishop Nicole Oresme discussed the possibility that the Earth rotated on its axis, while Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa in his Learned Ignorance asked whether there was any reason to assert that the Sun (or any other point) was the center of the universe.

In parallel to a mystical definition of God, Cusa wrote that "Thus the fabric of the world (machina mundi) will quasi have its center everywhere and circumference nowhere,"[63] recalling Hermes Trismegistus.

[85] The state of knowledge on planetary theory received by Copernicus is summarized in Georg von Peuerbach's Theoricae Novae Planetarum (printed in 1472 by Regiomontanus).

This issue was also resolved in the geocentric Tychonic system; the latter, however, while eliminating the major epicycles, retained as a physical reality the irregular back-and-forth motion of the planets, which Kepler characterized as a "pretzel".

Although he was in good standing with the Church and had dedicated the book to Pope Paul III, the published form contained an unsigned preface by Osiander defending the system and arguing that it was useful for computation even if its hypotheses were not necessarily true.

Some years after the publication of De Revolutionibus John Calvin preached a sermon in which he denounced those who "pervert the order of nature" by saying that "the sun does not move and that it is the earth that revolves and that it turns".

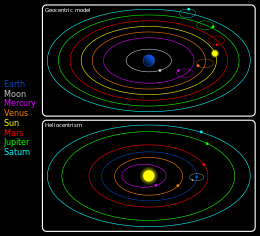

[95][d] Prior to the publication of De Revolutionibus, the most widely accepted system had been proposed by Ptolemy, in which the Earth was the center of the universe and all celestial bodies orbited it.

According to the correspondence of Gaspar Schopp of Breslau, he is said to have made a threatening gesture towards his judges and to have replied:[107] Maiori forsan cum timore sententiam in me fertis quam ego accipiam ("Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it").

On 17 February 1600, in the Campo de' Fiori (a central Roman market square), naked, with his "tongue imprisoned because of his wicked words", he was burned alive at the stake.

In February 1615, prominent Dominicans including Thomaso Caccini and Niccolò Lorini brought Galileo's writings on heliocentrism to the attention of the Inquisition, because they appeared to violate Holy Scripture and the decrees of the Council of Trent.

[122] According to Maurice Finocchiaro, Ingoli had probably been commissioned by the Inquisition to write an expert opinion on the controversy, and the essay provided the "chief direct basis" for the ban.

[125] In February 1616, the Inquisition assembled a committee of theologians, known as qualifiers, who delivered their unanimous report condemning heliocentrism as "foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture."

"[126][127] Bellarmine personally ordered Galileo ...to abstain completely from teaching or defending this doctrine and opinion or from discussing it... to abandon completely... the opinion that the sun stands still at the center of the world and the earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing.In March 1616, after the Inquisition's injunction against Galileo, the papal Master of the Sacred Palace, Congregation of the Index, and the Pope banned all books and letters advocating the Copernican system, which they called "the false Pythagorean doctrine, altogether contrary to Holy Scripture.

"[128][129] In 1618, the Holy Office recommended that a modified version of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus be allowed for use in calendric calculations, though the original publication remained forbidden until 1758.

Galileo's response, Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems (1632), clearly advocated heliocentrism, despite his declaration in the preface that, I will endeavour to show that all experiments that can be made upon the Earth are insufficient means to conclude for its mobility but are indifferently applicable to the Earth, movable or immovable...[130] and his straightforward statement, I might very rationally put it in dispute, whether there be any such centre in nature, or no; being that neither you nor any one else hath ever proved, whether the World be finite and figurate, or else infinite and interminate; yet nevertheless granting you, for the present, that it is finite, and of a terminate Spherical Figure, and that thereupon it hath its centre...[130] Some ecclesiastics also interpreted the book as characterizing the Pope as a simpleton, since his viewpoint in the dialogue was advocated by the character Simplicio.

[134] In his Principles of Philosophy (1644), Descartes introduced a mechanical model in which planets do not move relative to their immediate atmosphere, but are constituted around space-matter vortices in curved space; these rotate due to centrifugal force and the resulting centripetal pressure.

[136] By 1686, the model was well enough established that the general public was reading about it in Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, published in France by Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle and translated into English and other languages in the coming years.

[138] Meanwhile, the Catholic Church remained opposed to heliocentrism as a literal description, but this did not by any means imply opposition to all astronomy; indeed, it needed observational data to maintain its calendar.

An annotated copy of Newton's Principia was published in 1742 by Fathers le Seur and Jacquier of the Franciscan Minims, two Catholic mathematicians, with a preface stating that the author's work assumed heliocentrism and could not be explained without the theory.

In spite of dropping its active resistance to heliocentrism, the Catholic Church did not lift the prohibition of uncensored versions of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus or Galileo's Dialogue.

Nieto merely rejected the new system on those grounds without much passion, whereas Cohn went so far as to call Copernicus "a first-born of Satan", though he also acknowledged that he would have found it difficult to proffer one particular objection based on a passage from the Talmud.

One, a commentary on Genesis titled Yafe’ah le-Ketz[148] written by R. Israel David Schlesinger resisted a heliocentric model and supported geocentrism.

However, there were two flaws in Herschel's methodology: magnitude is not a reliable index to the distance of stars, and some of the areas that he mistook for empty space were actually dark, obscuring nebulae that blocked his view toward the center of the Milky Way.

[157] Already in the early 19th century, Thomas Wright and Immanuel Kant speculated that fuzzy patches of light called nebulae were actually distant "island universes" consisting of many stellar systems.

However, "scientific arguments were marshalled against such a possibility," and this view was rejected by almost all scientists until the early 20th century, with Harlow Shapley's work on globular clusters and Edwin Hubble's measurements in 1924.

The concept of an absolute velocity, including being "at rest" as a particular case, is ruled out by the principle of relativity, also eliminating any obvious "center" of the universe as a natural origin of coordinates.