Historiography of Colonial Spanish America

[9] At the turn of the twentieth century, scholarly research on Spanish America saw the creation of college courses dealing with the region, the systematic training of professional historians in the field, and the founding of the first specialized journal, Hispanic American Historical Review.

With the expansion of the field in the late twentieth century, there has been the establishment of new subfields, the founding of new journals, and the proliferation of monographs, anthologies, and articles for increasingly specialized practitioners and readerships.

Volume Two focuses on economic and social history, with chapters on Blacks, Indians, and women, groups that were generally excluded from scholarly attention until the late twentieth century.

The Handbook of Latin American Studies, based in the Hispanic Division of the Library of Congress, annually publishes annotated bibliographies of new works in the field, with contributing editors providing an overview essay.

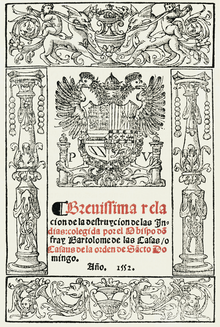

The so-called Black Legend drew on Bartolomé de Las Casas's contemporary critique, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552) and became an entrenched view of the Spanish colonial era.

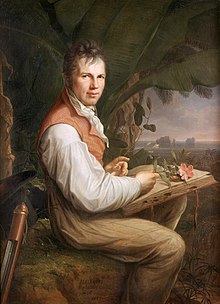

"In all but his strictly scientific works, Humboldt acted as the spokesman of the Bourbon Enlightenment, the approved medium, so to say, through which the collective inquiries of an entire generation of royal officials and creole savants were transmitted to the European public, their reception assured by the prestige of the author.

Alamán viewed crown rule during the colonial era as ideal, and political independence that after the brief monarchy of Agustín de Iturbide, the Mexican republic was characterized by liberal demagoguery and factionalism.

[73] In the United States, the work of William Hickling Prescott (1796–1859) on the conquests of Mexico and Peru became best sellers in the mid-nineteenth century, but were firmly based on printed texts and archival sources.

[101] A scholarly debate in the twentieth century concerned the so-called Black Legend, which characterized the Spanish conquest and its colonial empire as being uniquely cruel and Spaniards as fanatical and bigoted.

In the United States, Lewis Hanke's studies of Dominican Bartolomé de Las Casas opened the debate, arguing that Spain struggled for justice in its treatment of the indigenous.

The impacts of the demographic collapse has continued to garner attention following the early studies by Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah, who examined censuses and other materials to make empirical assessments.

[109] Noble David Cook's Born to Die[110] as well as Alfred Crosby's The Columbian Exchange are valuable and readable accounts of epidemic disease in the early colonial period.

"[115] In 1918 Harvard professor of history Clarence Haring published a monograph examining the legal structure of trade in the Habsburg era, followed by his major work on the Spanish empire (1947).

[118] One of the few women publishing scholarly works in the early twentieth century was Lillian Estelle Fisher, whose studies of the viceregal administration and the intendant system were important contributions to institutional.

[119][120] Other important works dealing with institutions are Arthur Aiton's biography of the first viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza, who set many patterns for future administrators in Spanish America.

[129] Jonathan I. Israel's work on seventeenth-century Mexico is especially important, showing how creole elites shaped state power by mobilizing the urban plebe to resist actions counter to their interests.

[150][151] In the late eighteenth century Spain was forcibly made aware in the Seven Years' War by the capture of Havana and Manila by the British, that it needed to establish a military to defend its empire.

[152][153][154][155][156] Scholars of Latin America have focused on characteristics of the region's populations, with particular interest in social differentiation and stratification, race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and family history, and the dynamics of colonial rule and accommodation or resistance to it.

An important 1972 essay by James Lockhart lays out a useful definition, "Social history deals with the informal, the unarticulated, the daily and ordinary manifestations of human existence, as a vital plasma in which all more formal and visible expressions are generated.

[169] Among elites are crown officials, high churchmen, mining entrepreneurs, and transatlantic merchants, enmeshed in various relationships wielding or benefiting from power as well as the women of this strata, who married well or took the veil.

In Tannenbaum's work, he argued that although slaves in Latin America were in forced servitude, they incorporated into society as Catholics, could sue for better treatment in Spanish courts, had legal routes to freedom, and in most places abolition was without armed conflict, such as the Civil War in the United States.

[222] The work is still a center of contention, with a number of scholars dismissing it as being wrong or outdated, while others consider the basic comparison still holding and simply no longer label it as the "Tannenbaum thesis.

In the decades following Tannenbaum's work, there were few of these documents, known cédulas de gracias al sacar, with just four cases identified, but the possibility of upward social mobility played an important role in framing scholarly analysis of dynamics of race in Spanish America.

Pamela Voekel's Alone Before God: Religious Origins of Modernity in Mexico shows how the crown targeted elaborate funerary rites and mourning as an expression of excessive public piety.

Seventeenth-century Mexican polymath secular priest Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora made astronomical observations as did his Jesuit contemporary Eusebio Kino.

In the earlier period, Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún's collection of information on Aztec classification "earthly" things in Book XI, such as the flora, fauna, soil types, land forms, and the like in the Florentine Codex was not clearly related to the project's religious aims.

[409] Transit over oceans or coastal sailing was relatively efficient compared to land transportation, and in most places in Spanish America there were few navigable rivers and no possibility of canal construction.

[418] The 2017 publication of Brian Hamnett's The End of Iberian Rule and the American Continent, 1770–1830[419] aims to show how independence came about in both Spanish America and Brazil, focusing on the contingency of that outcome.

Timothy Anna and Michael Costeloe have argued that the Bourbon monarchy collapsed, bringing into being new, sovereign nations, when American-born elites mainly sought autonomy within the existing system.

[421][422] Political scientist Jorge I. Domínguez writes in the same vein about the "breakdown of the Spanish American empire," arguing that independence was caused by international rivalries and not a splintering of colonial elites, whose conflicts he says could be managed within the existing framework.