Historiography of the Crusades

The historiography of the Crusades is the study of history-writing and the written history, especially as an academic discipline, regarding the military expeditions initially undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, or 13th centuries to the Holy Land.

Crusading was integral to Western European culture, with the ideas that shaped behaviour in the Late Middle Ages retaining currency beyond the 15th century in attitude rather than action.

The conflicts to which the term was applied were later extended to include other campaigns initiated, supported and sometimes directed by the Roman Catholic Church against pagans and heretics or for other alleged religious ends.

[2] From the first papal decree in 1095, these differed from other Christian religious wars in that they were considered a penitential exercise rewarding the participants with forgiveness for all confessed sins.

Pope Urban II was recorded to have said, as translated by Robert Somerville, "whoever for devotion alone not to obtain honour or money, goes to Jerusalem to liberate the Church of God can substitute the journey for all penance".

Historian Giles Constable identified four specific areas of focus for contemporary crusade studies; their political or geographical objectives, how they were organised, how far they were an expression of popular support, or the religious reasons behind them.

The First Crusade produced elaborate and engaging narratives written by participants conscious of their involvement in an unprecedented event whose success or failure was derived from divine intervention.

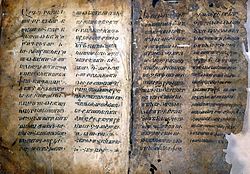

Ralph of Caen who arrived in 1108, wrote the Gesta Tancredi, extant in a single manuscript and written in idiosyncratic Latin about the exploits of Tancred, Prince of Galilee.

[20][21] Texts such as Gesta Francorum presented a view of crusading written from a French, Benedictine and Papalist perspective which emphasised the importance of military might and attributed success and failure to God's will.

This work provided the only significant challenge to the Papalist, northern French tradition and gained increasing importance before the end of the century, when the cosmopolitan Jerusalemite William of Tyre expanded on Albert's writing.

Little written evidence survives from the county of Edessa but much more from the kings of Jerusalem, the princes of Antioch, the counts of Tripol and the lordship of Joscelin III of Courtenay.

Historians now consider that, during this period, crusading expanded to include fighting the pagan Slavs in northern Europe, and the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula which is recorded in De expugnatione Lyxbonensi and the work known variously as theTeutonic Source or Lisbon Letter.

The Chronicle of the Morea is the key source for Frankish central and southern Greece in the 13th and the 14th fourteenth centuries and Assises de Romanie evidence legal systems.

Guillaume de Machaut's verse history La Prise d’Alixandre is the main source for the 1365 capture of the city of Alexandria in Egypt by Peter I of Cyprus.

Most narrative sources dealing with the Baltic Crusades were in High or Low German from associates of the Teutonic Order: Another Latin narrative is the chronicle of a Teutonic Order priest Peter von Dusburg Additionally, there are unique source types from the military campaigns including records of payments to mercenaries and some 100 different Litauische Wegeberichte describing campaign routes against Lithuania, compiled from scouts and local informants.

Other documents for both Prussia and Livonia, some only partly published, exist in the collection of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation or Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin.

Florentine chancellor Benedetto Accolti the Elder's De bello a Christianis contra barbaros gesto pro Christi sepulchro et Iudaea recuperandis on the First Crusade was closely linked with Pope Pius II's preparations for war.

The First Crusade was refashioned into a figure of pride and nationalism in works based on Robert of Rheims and William of Tyre such as Historiarum rerum Venetarum decades by Marcus Antonius Coccius Sabellicus and the De rebus gestis Francorum libri by Paolo Emilio which was dedicated to Louis XII.

[33] In the early 17th century, reformist Catholic theologians like Alberico Gentili and Dutch humanist Hugo Grotius argued only wars fought for secular motives, such as the defence of rightfully held land, could be defined as "just"; those undertaken to convert others were inherently "unjust".

[33] Enlightenment writers such as David Hume, Voltaire, and Edward Gibbon used crusading as a conceptual tool to critique religion, civilisation, and cultural mores.

They argued its only positive impact was ending feudalism and thus promoting rationalism; negatives included depopulation, economic ruin, abuse of papal authority, irresponsibility and barbarism.

[47] French historians such as Emmanuel Guillaume-Rey, Louis Madelin and René Grousset expanded on the thinking of Michaud, espoused propaganda of the country's Mediterranean colonies, and provided a source of popular models that were criticised and dismantled when empires ceased to hold academic approval.

It lost historiographical hegemony when democracy was restored in 1978, but remains fundamental within conservative sectors of Spanish academia, politics, and the media when analysing the medieval period because of the strong ideological connotations.

[52][53][54] In the 1940s, Claude Cahen's La Syrie du Nord a l'epoque des croisades—Northern Syria at the time of the Crusades— established the study of the Outremer as a feature of Near Eastern history removed from the West.

In The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: European Colonialism in the Middle Ages Prawer argued that Frankish settlement was too limited to be permanent and the Franks did not engage with the local culture or environment; it was therefore unlike the state of Israel.

The German historian Carl Erdmann presented a significant challenge, theorising that crusading was a political ideology within Western society rather than a glamourised frontier conflict.

[61] Following Chevedden's considerations, Paul Srodecki suggested to view the crusade as an evolutionary chameleon which only in this way could [...] survive within Latin Christendom up to the beginning of the early modern period and, during the Hussite and Turkish wars, continue to form an important ideological, rhetorical and thus both legitimistic and propagandistic instrument of the papacy as well as of the respective secular actors.

[55] In recent decades historians have deployed new approaches borrowed from gender studies and literary theory to examine the validity of narrative sources, developing insight on the experiences and representation of women within the context of the Crusades.

[69] Historical parallelism and the tradition of drawing inspiration from the Middle Ages have become keystones of political Islam encouraging ideas of a modern jihad and long struggle while secular Arab nationalism highlights the role of Western imperialism.

[71] Right-wing circles in the Western world have drawn opposing parallels by considering Christianity to be under an Islamic religious and demographic threat that is analogous to the situation at the time of the Crusades.