History of Hinduism

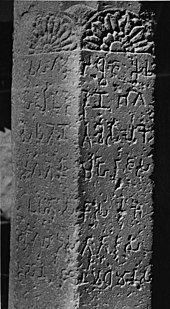

One seal showing a horned figure seated in a posture reminiscent of the Lotus position and surrounded by animals was named by early excavators "Pashupati", an epithet of the later Hindu gods Shiva and Rudra.

[56][57][58] Writing in 1997, Doris Meth Srinivasan said, "Not too many recent studies continue to call the seal's figure a 'Proto-Siva', rejecting thereby Marshall's package of proto-Shiva features, including that of three heads.

[60] In view of the large number of figurines found in the Indus valley, some scholars believe that the Harappan people worshipped a mother goddess symbolizing fertility, a common practice among rural Hindus even today.

[83] It has been suggested that the early Vedic religion focused exclusively on the worship of purely "elementary forces of nature by means of elaborate sacrifices", which did not lend themselves easily to anthropomorphological representations.

[90][107][web 5] In Iron Age India, during a period roughly spanning the 10th to 6th centuries BCE, the Mahajanapadas arise from the earlier kingdoms of the various Indo-Aryan tribes, and the remnants of the Late Harappan culture.

In this period the mantra portions of the Vedas are largely completed, and a flowering industry of Vedic priesthood organised in numerous schools (shakha) develops exegetical literature, viz.

At the same time, among the indigenous religions, a common allegiance to the authority of the Vedas provided a thin, but nonetheless significant, thread of unity amid their variety of gods and religious practices.

According to reports by two Chinese envoys, K'ang T'ai and Chu Ying, the state was established by an Indian Brahmin named Kaundinya, who in the 1st century CE was given instruction in a dream to take a magic bow from a temple and defeat a Khmer queen, Soma.

[178] Buddhism lost its position after the 8th century, due to the loss of financial support from royal donors and the lack of appeal among the rural masses, and began to disappear in India.

[note 34] The Brahmanism of the Dharmaśāstra and the smritis underwent a radical transformation at the hands of the Purana composers, resulting in the rise of Puranic Hinduism,[35] "which like a colossus striding across the religious firmanent soon came to overshadow all existing religions".

[35] With the breakdown of the Gupta empire, gifts of virgin waste-land were heaped on brahmanas,[40][182] to ensure profitable agrarian exploitation of land owned by the kings,[40] but also to provide status to the new ruling classes.

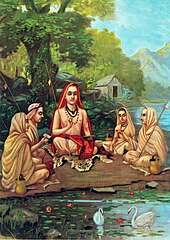

"[214][215] Shankara's position was further established in the 19th and 20th centuries, when neo-Vedantins and western Orientalists elevated Advaita Vedanta "as the connecting theological thread that united Hinduism into a single religious tradition".

[217] Hindu and also Buddhist religious and secular learning had first reached Persia in an organised manner in the 6th century, when the Sassanid Emperor Khosrow I (531–579) deputed Borzuya the physician as his envoy, to invite Indian and Chinese scholars to the Academy of Gondishapur.

[240][239] Teachers such as Ramanuja, Madhva, and Chaitanya aligned the Bhakti movement with the textual tradition of Vedanta, which until the 11th century was only a peripheral school of thought,[209] while rejecting and opposing the abstract notions of Advaita.

[241][242][page needed] According to Nicholson, already between the 12th and the 16th century, "certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the 'six systems' (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy.

[253] The empire's founders, Harihara I and Bukka Raya I, were devout Shaivas (worshippers of Shiva), but made grants to the Vaishnava order of Sringeri with Vidyaranya as their patron saint, and designated Varaha (the boar, an avatar of Vishnu) as their emblem.

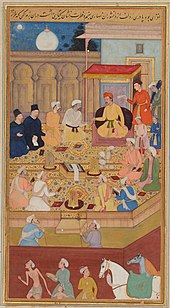

However, during Mughal history, at times, subjects had the freedom to practise any religion of their choice, though kafir able-bodied adult males with income were obliged to pay the jizya, which signified their status as dhimmis.

Aurangzeb was comparatively less tolerant of other faiths than his predecessors had been; and has been subject to controversy and criticism for his policies that abandoned his predecessors' legacy of pluralism, citing his introduction of the jizya tax, doubling of custom duties on Hindus while abolishing it for Muslims, destruction of Hindu temples, forbidding construction and repairs of some non-Muslim temples, and the executions of Maratha ruler Sambhaji[277][278] and the ninth Sikh guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur,[237] and his reign saw an increase in the number and importance of Islamic institutions and scholars.

He led many military campaigns against the remaining non-Muslim powers of the Indian subcontinent – the Sikh states of Punjab, the last independent Hindu Rajputs and the Maratha rebels – as also against the Shia Muslim kingdoms of the Deccan.

Under their ambitious leader Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the Maratha freed themselves from the Muslim sultans of Bijapur to the southeast and, becoming much more aggressive, began to frequently raid Mughal territory.

[web 18] King Prithvi Narayan Shah, the last Gorkhali monarch, self-proclaimed the newly unified Kingdom of Nepal as Asal Hindustan ("Real Land of Hindus") due to North India being ruled by the Islamic Mughal rulers.

[283] After the Gorkhali conquest of Kathmandu valley, King Prithvi Narayan Shah expelled the Christian Capuchin missionaries from Patan and revisioned Nepal as Asal Hindustan ("real land of Hindus").

[288] The Battle of Plassey would see the emergence of the British as a political power; their rule later expanded to cover much of India over the next hundred years, conquering all of the Hindu states on the Indian subcontinent,[289] with the exception of the Kingdom of Nepal.

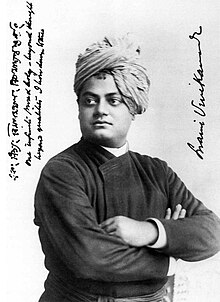

Western orientalist searched for the "essence" of the Indian religions, discerning this in the Vedas,[303] and meanwhile creating the notion of "Hinduism" as a unified body of religious praxis[135] and the popular picture of 'mystical India'.

An early champion of Indian-inspired thought in the West was Arthur Schopenhauer who in the 1850s advocated ethics based on an "Aryan-Vedic theme of spiritual self-conquest", as opposed to the ignorant drive toward earthly utopianism of the superficially this-worldly "Jewish" spirit.

[317] Helena Blavatsky moved to India in 1879, and her Theosophical Society, founded in New York in 1875, evolved into a peculiar mixture of Western occultism and Hindu mysticism over the last years of her life.

In the early 20th century, Western occultists influenced by Hinduism include Maximiani Portaz – an advocate of "Aryan Paganism" – who styled herself Savitri Devi and Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, founder of the German Faith Movement.

Influential 20th-century Hindus were Ramana Maharshi, B. K. S. Iyengar, Paramahansa Yogananda, Prabhupada (founder of ISKCON), Sri Chinmoy, Swami Rama and others who translated, reformulated and presented Hinduism's foundational texts for contemporary audiences in new iterations, raising the profiles of Yoga and Vedanta in the West and attracting followers and attention in India and abroad.

Samuel (2010, p. 199): "By the first and second centuries CE, the Dravidian-speaking regions of the south were also increasingly being incorporated into the general North and Central Indian cultural pattern, as were parts at least of Southeast Asia.

The Pallava kingdom in South India was largely Brahmanical in orientation although it included a substantial Jain and Buddhist population, while Indic states were also beginning to develop in Southeast Asia."