History of general anesthesia

Throughout recorded history, attempts at producing a state of general anesthesia can be traced back to the writings of ancient Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Akkadians, Egyptians, Persians, Indians, and Chinese.

[1][2][3][4][13][20][24][25][26] The late 19th century also saw major advancements to modern surgery with the development and application of antiseptic techniques as a result of the germ theory of disease, which significantly reduced morbidity and mortality rates.

Moreover, the application of economic and business administration principles to healthcare in the late 20th and early 21st centuries led to the introduction of management practices, such as transfer pricing, to improve the efficiency of anesthetists.

[37] The most ancient testimony concerning the opium poppy found to date was inscribed in cuneiform script on a small white clay tablet at the end of the third millennium BC.

Knowledge and use of the opium poppy and its euphoric effects thus passed to the Babylonians, who expanded their empire eastwards to Persia and westwards to Egypt, thereby extending its range to these civilizations.

[57][58][59] Before the surgery, he administered an oral anesthetic potion, probably dissolved in wine, in order to induce a state of unconsciousness and partial neuromuscular blockade.

Many sinologists and scholars of traditional Chinese medicine have guessed at the composition of Hua Tuo's mafeisan powder, but the exact components still remain unclear.

[74] One can find records of dwale in numerous literary sources, including Shakespeare's Hamlet, and the John Keats poem "Ode to a Nightingale".

[74] In the 13th century, we have the first prescription of the "spongia soporifica"—a sponge soaked in the juices of unripe mulberry, flax, mandragora leaves, ivy, lettuce seeds, lapathum, and hemlock with hyoscyamus.

[citation needed] He called it oleum dulce vitrioli, a name that reflects the fact that it is synthesized by distilling a mixture of ethanol and sulfuric acid (known at that time as oil of vitriol).

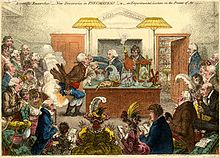

With an eye toward making further advances in this new science as well as offering treatment for diseases previously thought to be untreatable (such as asthma and tuberculosis), Beddoes founded the Pneumatic Institution for inhalation gas therapy in 1798 at Dowry Square in Clifton, Bristol.

He was, however, the first to document the analgesic effects of nitrous oxide, as well as its potential benefits in relieving pain during surgery:[81] As nitrous oxide in its extensive operation appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place.Takamine Tokumei from Shuri, Ryūkyū Kingdom, is reported to have made a general anesthesia in 1689 in the Ryukyus, now known as Okinawa.

Like that of Hua Tuo, this compound was composed of extracts of several different plants, including:[84][85][86] The active ingredients in tsūsensan are scopolamine, hyoscyamine, atropine, aconitine and angelicotoxin.

In 1824, Hickman submitted the results of his research to the Royal Society in a short treatise titled Letter on suspended animation: with the view of ascertaining its probable utility in surgical operations on human subjects.

Horace Wells, a Connecticut dentist present in the audience that day, immediately seized upon the significance of this apparent analgesic effect of nitrous oxide.

[107] In 1847, Scottish obstetrician James Young Simpson (1811–1870) of Edinburgh was the first to use chloroform as a general anesthetic on a human (Robert Mortimer Glover had written on this possibility in 1842 but only used it on dogs).

[102] After Austrian diplomat Karl von Scherzer brought back sufficient quantities of coca leaves from Peru, in 1860 Albert Niemann isolated cocaine, which thus became the first local anesthetic.

[110][111] In 1871, the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844–1924) published a paper describing the first successful elective human tracheotomy to be performed for the purpose of administration of general anesthesia.

[112][113][114][115] In 1880, the Scottish surgeon William Macewen (1848–1924) reported on his use of orotracheal intubation as an alternative to tracheotomy to allow a patient with glottic edema to breathe, as well as in the setting of general anesthesia with chloroform.

[116][117][118] All previous observations of the glottis and larynx (including those of Manuel García,[119] Wilhelm Hack[120][121] and Macewen) had been performed under indirect vision (using mirrors) until 23 April 1895, when Alfred Kirstein (1863–1922) of Germany first described direct visualization of the vocal cords.

[129] An American anesthesiologist practicing at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, Janeway was of the opinion that direct intratracheal insufflation of volatile anesthetics would provide improved conditions for otolaryngologic surgery.

[124] In 1928 Arthur Ernest Guedel introduced the cuffed endotracheal tube, which allowed deep enough anesthesia that completely suppressed spontaneously respirations while the gas and oxygen were delivered via positive pressure ventilation controlled by the anesthesiologist.

[131] This allowed the development of thoracic surgery, which had previously been vexed by the pendelluft [132] problem in which the bad lung being operated on inflated with patient exhalation due to the loss of vacuum with the thorax being open to the atmosphere.

Working at the Queen's Hospital for Facial and Jaw Injuries in Sidcup with plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies (1882–1960) and anesthetist E. Stanley Rowbotham (1890–1979), Magill developed the technique of awake blind nasotracheal intubation.

[149] Although initially used to reduce the sequelae of spasticity associated with electroconvulsive therapy for psychiatric disease, curare found use in the operating rooms at Bellvue by E.M. Papper and Stuart Cullen in the 1940s using preparations made by Squibb.

[109] Mechanical ventilation first became common place with the polio epidemics of the 1950s, most notably in Denmark where an outbreak in 1952 lead to the creation of critical care medicine out of anesthesia.

[152] In 1949, Macintosh published a case report describing the novel use of a gum elastic urinary catheter as an endotracheal tube introducer to facilitate difficult tracheal intubation.

[153] Inspired by Macintosh's report, P. Hex Venn (who was at that time the anesthetic advisor to the British firm Eschmann Bros. & Walsh, Ltd.) set about developing an endotracheal tube introducer based on this concept.

These in turn were replaced by the current standards of isoflurane, sevoflurane, and desflurane in the eighties and nineties although methoxyflurane remains in use for prehospital anesthesia in Australia as Penthrox.

Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes which employ digital technology such as the CMOS active pixel sensor (APS) to generate a view of the glottis so that the trachea may be intubated.