Pi

[1][2] The earliest known use of the Greek letter π to represent the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter was by the Welsh mathematician William Jones in 1706.

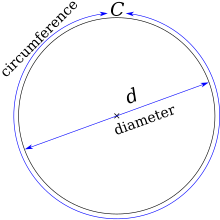

The symbol used by mathematicians to represent the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter is the lowercase Greek letter π, sometimes spelled out as pi.

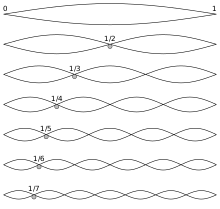

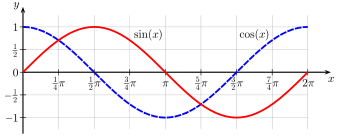

One such definition, due to Richard Baltzer[14] and popularized by Edmund Landau,[15] is the following: π is twice the smallest positive number at which the cosine function equals 0.

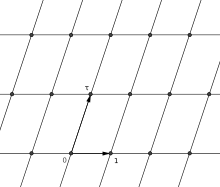

In the polar coordinate system, one number (radius or r) is used to represent z's distance from the origin of the complex plane, and the other (angle or φ) the counter-clockwise rotation from the positive real line:[41]

This formula establishes a correspondence between imaginary powers of e and points on the unit circle centred at the origin of the complex plane.

[36][45] Although some pyramidologists have theorized that the Great Pyramid of Giza was built with proportions related to π, this theory is not widely accepted by scholars.

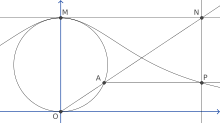

[47] The first recorded algorithm for rigorously calculating the value of π was a geometrical approach using polygons, devised around 250 BC by the Greek mathematician Archimedes, implementing the method of exhaustion.

[55] Around 265 AD, the Wei Kingdom mathematician Liu Hui created a polygon-based iterative algorithm and used it with a 3,072-sided polygon to obtain a value of π of 3.1416.

[69] Although infinite series were exploited for π most notably by European mathematicians such as James Gregory and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the approach also appeared in the Kerala school sometime in the 14th or 15th century.

[70][71] Around 1500 AD, a written description of an infinite series that could be used to compute π was laid out in Sanskrit verse in Tantrasamgraha by Nilakantha Somayaji.

In the 1660s, the English scientist Isaac Newton and German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz discovered calculus, which led to the development of many infinite series for approximating π. Newton himself used an arcsine series to compute a 15-digit approximation of π in 1665 or 1666, writing, "I am ashamed to tell you to how many figures I carried these computations, having no other business at the time.

, it converges impractically slowly (that is, approaches the answer very gradually), taking about ten times as many terms to calculate each additional digit.

[87] In 1844, a record was set by Zacharias Dase, who employed a Machin-like formula to calculate 200 decimals of π in his head at the behest of German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss.

When Euler solved the Basel problem in 1735, finding the exact value of the sum of the reciprocal squares, he established a connection between π and the prime numbers that later contributed to the development and study of the Riemann zeta function:[95]

In 1882, German mathematician Ferdinand von Lindemann proved that π is transcendental,[97] confirming a conjecture made by both Legendre and Euler.

[107][104] The earliest known use of the Greek letter π alone to represent the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter was by Welsh mathematician William Jones in his 1706 work Synopsis Palmariorum Matheseos; or, a New Introduction to the Mathematics.

[103][109] Euler started using the single-letter form beginning with his 1727 Essay Explaining the Properties of Air, though he used π = 6.28..., the ratio of periphery to radius, in this and some later writing.

[113] Because Euler corresponded heavily with other mathematicians in Europe, the use of the Greek letter spread rapidly, and the practice was universally adopted thereafter in the Western world,[102] though the definition still varied between 3.14... and 6.28... as late as 1761.

[125] This effort may be partly ascribed to the human compulsion to break records, and such achievements with π often make headlines around the world.

[124] The fast iterative algorithms were anticipated in 1914, when Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan published dozens of innovative new formulae for π, remarkable for their elegance, mathematical depth and rapid convergence.

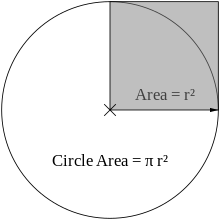

[152]π appears in formulae for areas and volumes of geometrical shapes based on circles, such as ellipses, spheres, cones, and tori.

[156] Definite integrals that describe circumference, area, or volume of shapes generated by circles typically have values that involve π.

The uncertainty principle gives a sharp lower bound on the extent to which it is possible to localize a function both in space and in frequency: with our conventions for the Fourier transform,

The appearance of π in the formulae of Fourier analysis is ultimately a consequence of the Stone–von Neumann theorem, asserting the uniqueness of the Schrödinger representation of the Heisenberg group.

[176] One of the key tools in complex analysis is contour integration of a function over a positively oriented (rectifiable) Jordan curve γ.

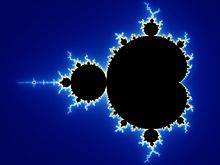

[191] The solution to the Basel problem implies that the geometrically derived quantity π is connected in a deep way to the distribution of prime numbers.

[20] As a result, the constant π is the unique number such that the group T, equipped with its Haar measure, is Pontrjagin dual to the lattice of integral multiples of 2π.

The Cauchy distribution plays an important role in potential theory because it is the simplest Furstenberg measure, the classical Poisson kernel associated with a Brownian motion in a half-plane.

The constant π is the unique (positive) normalizing factor such that H defines a linear complex structure on the Hilbert space of square-integrable real-valued functions on the real line.

An early example of a mnemonic for pi, originally devised by English scientist James Jeans, is "How I want a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics.