History of Czechs in Baltimore

The population began to decline during the mid-to-late 20th century, as the community assimilated and aged, while many Czech Americans moved to the suburbs of Baltimore.

[17] The second Bohemian Jew in Maryland was Levi Collmus, a dry goods dealer from Prague, who arrived at the Port of Baltimore in September, 1806.

[20] The pioneer Reform rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, born in Plesná, Bohemia, played an influential role in the establishment of the synagogue.

[29] Prior to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, racially restrictive covenants were used in Baltimore to exclude African-Americans and other minority groups.

[32] Some of these associations were Jednota "Blesk", "Vlastimila" (sisters' benevolent union), the "Ctirada", the "Jaromíra", and the "Zlatá Praha" ("Golden Prague").

[24] In August 1879, the Fairmount and Chapel Streets Permanent Building, Savings and Loan Association No 1 Inc. was founded to serve the needs of Czech immigrants.

[37] Shimek's Bohemian Hall, now the United Baptist Church at Barnes Street and Broadway, was located in the heart of Little Bohemia and was established as a meeting place for the Czech community.

[38] Shimek allowed the Hall to be used to hold Knights of Labor meetings for working-class Czech tailors and garment workers.

[40] While the majority of Baltimore's Bohemians were Catholic, the Czech-Slovak Protective Society was largely composed of secular and religious freethinkers.

[41] In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Bohemian stronghold north of Johns Hopkins Hospital along the Baltimore to New York Amtrak line all the way to Frank C Bocek Park was known by the now long-forgotten name of "Swampoodle".

[43] The heart of the Bohemian "hollow" of Swampoodle was located just north of Johns Hopkins Hospital along the tiny side streets of Barnes and Abbott.

One Slovak-American woman from a multiethnic family on North Bradford Street described her kitchen as "a league of nations around that dining-room table.

[48] As late as the 1930s and 1940s it was not uncommon for Slavic Catholics, such as Czechs and Poles, to be called ethnic and religious slurs such as "bohunks" and "fish eaters."

[59] During World War I (1914–1918), most of Baltimore's garment industry workers were still of Bohemian, Lithuanian, and Russian descent, the majority of whom were Jewish and many of whom were young women.

[24] Many working-class Central and Eastern European immigrants, including Czechs, settled in the Curtis Bay neighborhood in the late 1800s and early 1900s, where many attended the St. Athanasius Roman Catholic Church.

[24] After the War, Czechs and Slovaks concentrated in the Collington Avenue area began to move out of the neighborhood and dispersed widely across Baltimore city.

[35] During the 1964 presidential election, leaders of the Maryland Democratic Party directed a campaign against George Wallace in the ethnic neighborhoods of East Baltimore, which included deploying "big name" politicians and dispensing free beer to the locals.

Senator Daniel Brewster's election campaign especially targeted the Bohemian, Italian, and Polish areas of Baltimore populated by unionized skilled workers.

[68] By 1969, the Czech-American community in Little Bohemia was predominantly composed of ageing homeowners who lived alongside more recently arrived African-American residents.

[62] The Slavie Federal Savings and Loan Association closed its original location on Collington Avenue near Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1993.

The neighborhood, now known as Middle East, has suffered from extensive urban decay and housing abandonment due to poverty and crime, as well as the after-effects of the Baltimore riot of 1968, and now has a largely poverty-class and working-class African-American majority.

[23] The neighborhood was one of the hardest hit in Baltimore, as the white working-class and middle-class African-American tax base left and the area was effected by epidemics of heroin, crack cocaine, and HIV, along with an intensification of gang activity fueled by the drug trade.

Crime and domestic violence rates were double those of the city as a whole, and the incidence of lead poisoning and child abuse were among the highest in Baltimore.

The festival is held at St. Mary's Assumption Eastern Rite Catholic Church in the Baltimore suburb of Joppa and is the first Pan-Slavic festival in the Baltimore area, bringing together 13 Slavic heritages - Czech, Slovak, Ukrainian, Polish, Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Slovenian, Montenegrin, Belarusian, Macedonian and Lemko.

The Bulgarian Embassy has sent dancers to the festival and a variety of Slavic foods are served, including pierogi, borscht, and holupki.

[92] The Pride Center of Maryland offers Czech-language services to gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender clients in the Greater Baltimore region.

[93] A few reminders of the city's Czech heritage exist in local place names, most notably Moravia Road, the Moravia-Walther neighborhood, Frank C Bocek Park, and Prague Avenue near Rosedale.

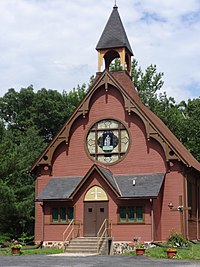

[96] The Czech Presbyterians first organized a congregation in 1890, first holding services at Faith Chapel on Broadway just north of Shimek's Bohemian Hall.

[97] Chevrei Tzedek Congregation, a Conservative synagogue in Baltimore, is home to one of the 1,564 Torah scrolls rescued by the Jewish community of Prague during World War II.

The scroll has suffered serious water damage to the Book of Exodus while in storage under the Communist government of Czechoslovakia, but is in excellent condition from Leviticus to Deuteronomy.